Meet XPR1: The Phosphate Channel That’s Not What We Thought!

Okay, So What’s the Big Deal About Phosphate?

Alright, let’s dive into the fascinating world happening inside our cells. You know how important balance is, right? Well, the same goes for tiny molecules like inorganic phosphate, or Pi. It’s absolutely vital for pretty much everything our cells do – making energy, building stuff, sending signals. If Pi levels get out of whack, things go wrong, fast.

Our cells are pretty clever about keeping Pi levels just right. They bring it in when they need it, and they kick it out when there’s too much. Bringing it in? We’ve got a decent handle on that. But kicking it out? That’s been a bit of a mystery, especially when it comes to the main player in mammals: a protein called XPR1.

For a long time, we thought XPR1 was just another one of those workhorse proteins called ‘transporters’. These guys usually grab a molecule on one side of the cell membrane and shuttle it across, often changing shape as they do it. XPR1 was known to export Pi, and it even got tangled up with some retroviruses (like a cellular door they could sneak through!), but its actual mechanism for moving Pi was fuzzy. And get this – when XPR1 goes wrong, it’s linked to some serious health issues, like a weird brain disorder called Primary Familial Brain Calcification (PFBC) and even certain cancers. So, understanding exactly how this protein works isn’t just academic; it’s super important for health.

Turns Out, XPR1 is a Channel, Not a Transporter!

So, we had this big question: How does XPR1 actually move Pi out of the cell? Does it work like other known Pi transporters? Well, spoiler alert: the answer is a resounding no!

This is where some seriously cool science comes in. Using a super-powerful technique called cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which lets us see the 3D structure of tiny molecules like proteins in incredible detail, we finally got a good look at human XPR1. And what we saw was totally unexpected. Its structure is completely different from any known ion transporter. It doesn’t look like the usual shuttle-service proteins at all.

This structural weirdness got us thinking. If it’s not a transporter, what is it? The structure hinted that it might be something else entirely – an ion channel. Now, channels are different. Think of them less like a shuttle and more like a tunnel or a pore through the cell membrane. They open and close, letting specific ions or molecules rush through when they’re open, usually driven by electrical voltage or concentration differences.

To test this channel idea, we did some fancy electrical experiments called patch clamp recordings. We basically stuck tiny electrodes onto membranes containing XPR1 and measured the electrical currents flowing through. And bingo! We saw currents that behaved exactly like those flowing through an ion channel. These currents were dependent on both the electrical voltage across the membrane and, crucially, on the presence of Pi. Plus, the currents were *large*, much larger than you’d expect from a typical transporter. This strongly suggested XPR1 is indeed a channel, and it’s permeable to Pi!

We also did experiments using artificial membrane bubbles (called proteoliposomes) with XPR1 inside and showed that Pi actually moves across the membrane, and this movement is boosted by voltage, just like you’d expect from a channel.

Peering Inside the XPR1 Channel

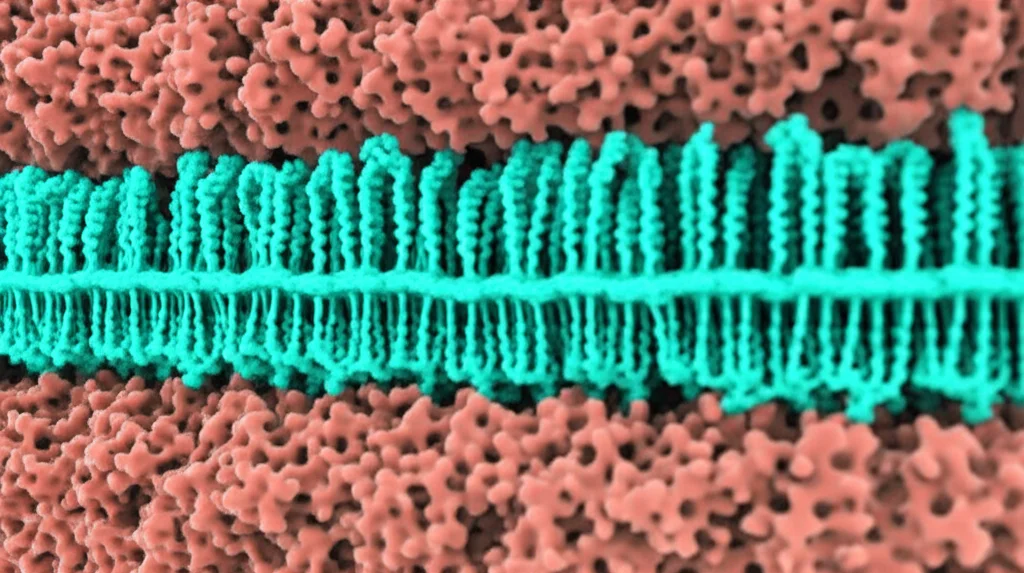

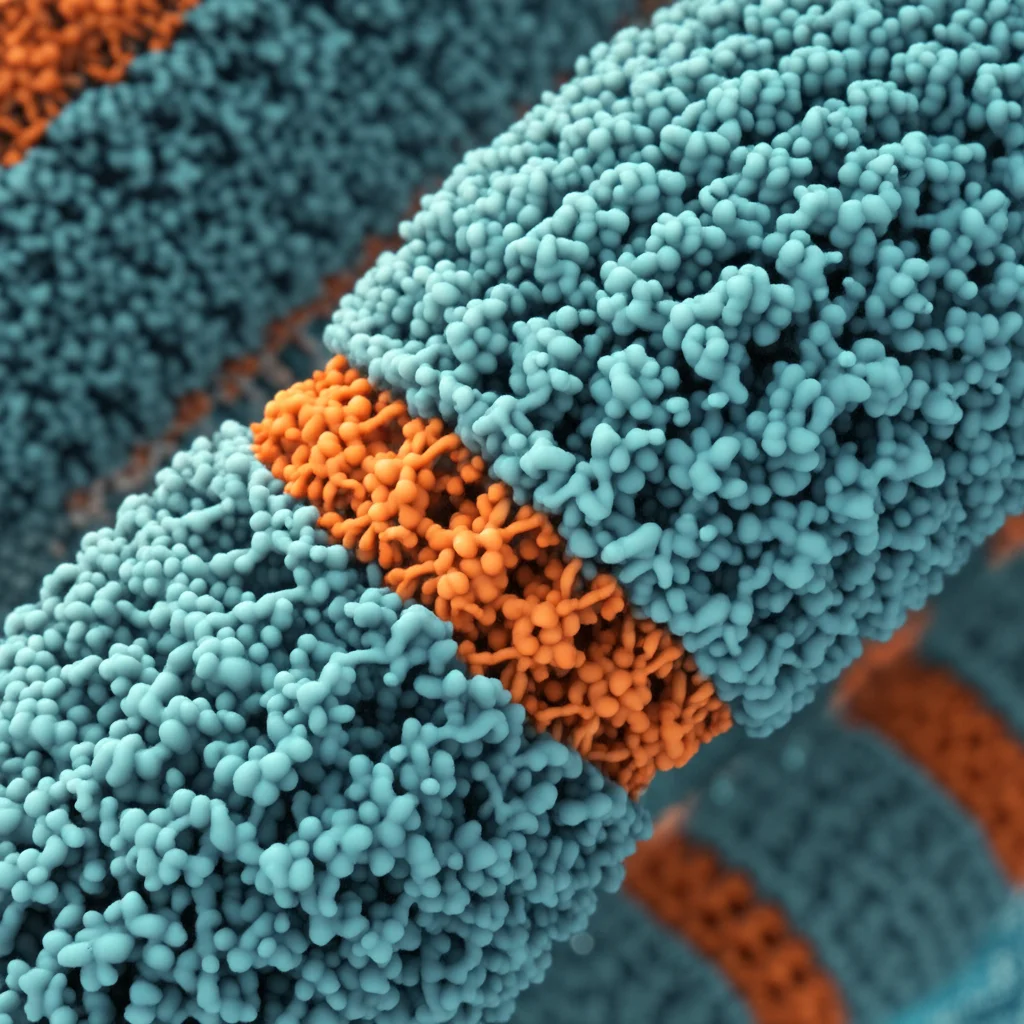

Okay, so it’s a channel. But what does this channel tunnel actually look like? Our cryo-EM structures gave us the answer. The protein has two main parts: a blobby bit inside the cell (the SPX domain, which acts like a Pi sensor) and a part that sits right in the membrane (the transmembrane domain, or TMD).

The TMD, which forms the channel itself, is made of several rod-like structures called alpha-helices. Instead of the 8 helices we thought it had before, it actually has 10! And six of these helices (TM5-10) are arranged in a circle, forming a barrel-like structure right in the middle. Inside this barrel? A tunnel! This tunnel is open towards the inside of the cell and has a positively charged lining, which makes perfect sense if it’s letting negatively charged Pi ions through.

We could even trace a potential pathway for Pi through this tunnel using computer programs. It’s like a little winding path with a narrow spot about 3 Ångstroms wide (that’s tiny!).

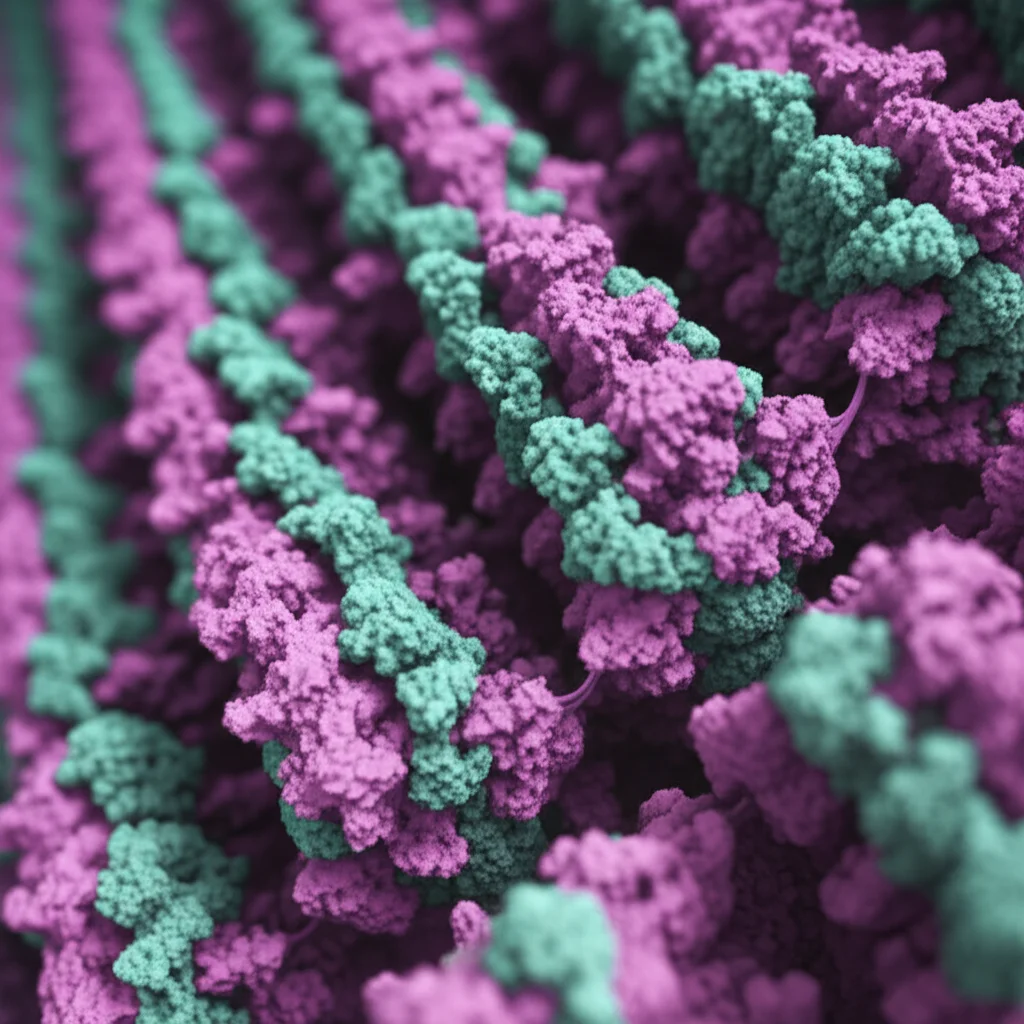

Where Does Pi Hang Out in the Channel?

To figure out exactly where Pi might travel or pause within the channel, we solved the structure of XPR1 again, but this time with Pi present. And guess what? We saw extra blobs of density inside the tunnel that weren’t there before. These are almost certainly Pi ions caught in the act of moving through!

Based on these densities, we identified two spots in the tunnel that look like they’re designed to hold onto Pi temporarily. These spots are surrounded by positively charged amino acids, especially arginines (like Arg459, Arg570, Arg603, and Arg604). These positively charged residues are perfectly positioned to interact with the negatively charged Pi. It’s like little waiting stations or coordination sites along the pathway.

To prove these spots are important for Pi movement, we did some experiments where we changed some of these key arginine residues to something neutral, like alanine (this is called mutagenesis). When we mutated Arg570, for example, the protein was much worse at transporting Pi in our flux assays. And in patch clamp, the R570A mutant showed reduced Pi permeability, especially at higher Pi concentrations, which is the opposite of what the normal protein does! This strongly supports the idea that Arg570 is crucial for Pi coordination and movement through the channel.

Linking Structure to Disease

Remember how I mentioned XPR1 is linked to diseases like PFBC and cancer? Our new structures give us clues why. We could map where the mutations found in PFBC patients are located on the XPR1 protein.

Many mutations are in the SPX domain, the part that senses Pi levels. But some are right there in the channel part, within that TM5-10 barrel that forms the pore! Specifically, mutations in residues like Arg459 and Arg570 (yes, the same Arg570 we mutated!) are known to reduce Pi export. Seeing these critical residues located right in the putative Pi pathway in our structure makes perfect sense. A change here would directly mess up Pi movement through the channel, leading to problems with Pi balance in the cell and potentially causing disease.

Other disease-linked mutations are in the protein’s tail, which connects the channel part to the SPX sensor. This suggests the tail might act as a bridge, helping the SPX sensor tell the channel when to open or close based on Pi levels.

How Does This Channel Open and Close?

Our cryo-EM structures, both with and without Pi, seem to show XPR1 in a ‘closed’ state. The tunnel is blocked towards the outside of the cell by a segment of one of the helices (TM9), like a door being shut.

So, how does it open to let Pi out? We think that TM9, which is tilted in the closed structure, might bend or kink. This kinking would move the blocking segment out of the way, creating a continuous tunnel all the way through the membrane. Computer predictions and structures from other labs published recently support this idea – they found XPR1 structures where TM9 *is* kinked, and the pore is open. It’s like a molecular switch where the bending of one part opens the gate for Pi to escape.

The ‘Escape Valve’ Idea

If XPR1 is a channel that can let Pi (and maybe other negative ions) through, why don’t our cells just leak Pi constantly? This is where regulation comes in. Our patch clamp experiments showed that XPR1 activity is tightly controlled by two main things:

- Voltage: The channel prefers to open when the inside of the cell is electrically negative compared to the outside. This is exactly the condition that would push negatively charged Pi *out* of the cell.

- Internal Pi concentration: The channel is much more active when there’s a lot of Pi inside the cell.

This makes perfect sense for a Pi exporter! It only opens when the conditions are right for Pi to leave (negative voltage) and when there’s excess Pi inside (high internal Pi). It’s like a safety valve that only opens when pressure (high Pi) builds up and the electrical gradient favors release.

There’s also evidence that other molecules, like special forms of inositol polyphosphates (InsP7 and InsP8), might be needed to fully activate XPR1, especially when Pi is really high. These molecules are only made transiently when Pi is in excess. This adds another layer of control, ensuring XPR1 only opens briefly when needed.

This tightly regulated opening could explain phenomena observed in cells where Pi is released very quickly, sometimes called a “phosphate flush.” XPR1 seems perfectly designed to mediate this kind of rapid, controlled Pi release.

Wrapping It Up

So, the big takeaway here is that XPR1, the main mammalian Pi exporter, isn’t a transporter after all. It’s a unique, voltage- and Pi-activated ion channel! We’ve seen its never-before-seen structure, identified the pore where Pi likely travels, pinpointed potential Pi binding sites, and shown how mutations in these key areas can mess things up, potentially leading to diseases like PFBC.

This discovery completely changes how we think about Pi export and gives us exciting new avenues to explore. Understanding this channel’s structure and how it’s regulated by voltage, Pi, and potentially other molecules is crucial. It opens the door (pun intended!) to figuring out exactly how XPR1 dysfunction causes disease and, hopefully, finding new ways to treat them. It’s a pretty cool time to be studying cellular plumbing!

Source: Springer