Boats to the Beyond? Water, Symbolism, and the Xiaohe Burials

Well hello there! Let me tell you about a place that’s just captured my imagination – the Xiaohe site. Imagine a Bronze Age community nestled in the heart of the hyperarid Tarim Basin. Sounds like a tough place to live, right? But these folks, the Xiaohe culture, they weren’t just surviving; they were thriving, deeply connected to the rivers and oases that sustained them. And their burials? Absolutely fascinating, thanks to the incredible preservation out there in the desert.

We’re talking about a culture that popped up seemingly out of nowhere around 1950 BCE and stuck around until about 1400 BCE. They cultivated wheat and millet, herded cattle (and boy, did cattle play a role in their lives and deaths!), and left behind some truly unique archaeological puzzles.

A Glimpse into the Past

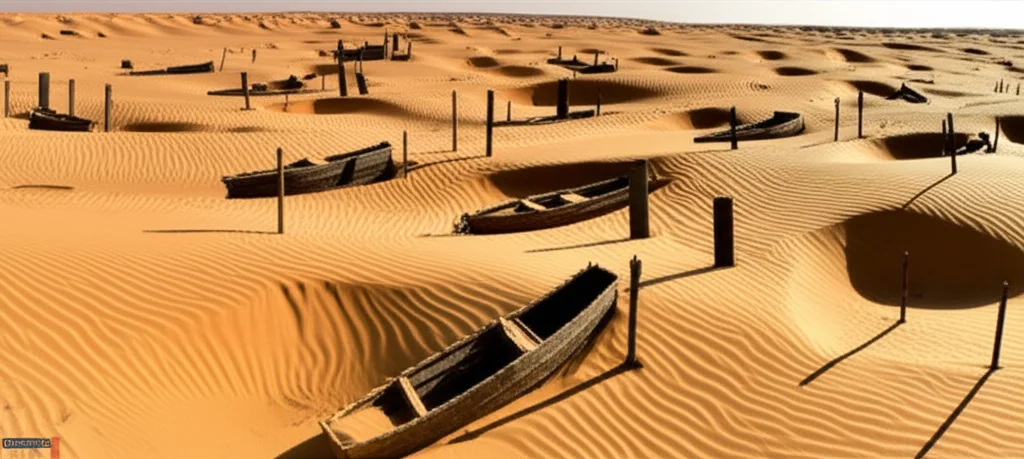

The Xiaohe cemetery itself is quite a sight, a mound rising about 7 meters from the desert floor. Swedish archaeologist F. Bergman first documented a dozen graves back in the 1930s, but it was the extensive excavation in the early 2000s that really opened the floodgates (pun intended!) on our understanding. Over 160 more graves were uncovered, giving us an unprecedented look at their funerary practices.

What’s amazing is the organic preservation. We’re not just finding bones and pottery shards; we’re finding wooden coffins, cattle hides, even traces of food and drink like milk and kefir! This level of detail is a dream for archaeologists, allowing for all sorts of scientific analyses, from genetics to diet. But beyond the science, I find it offers a rare chance to delve into something trickier: meaning and symbolism.

Boats, Cattle, and Mystery

The burials at Xiaohe come in a few types, but the most common one is truly distinctive. Picture this: a narrow wooden coffin, often described as “boat-shaped,” buried in a sand pit. At the head of the coffin, upright wooden poles were erected. Some coffins were covered in cattle hides, and painted bovine skulls were sometimes included. Cattle were clearly central, not just for food but for ritual, which makes sense given their need for water in an oasis environment compared to, say, sheep or goats favored by surrounding cultures.

Now, about those poles. Early interpretations often saw them as symbols for sexual organs – straight poles with red tips as male, and those with dark, oval ends as female. It’s a straightforward, processual approach to symbolism, trying to link a shape directly to a social marker. But here’s where it gets tricky: sometimes, these symbols were “reversed,” appearing on graves of the opposite biological sex. That makes you pause and think, doesn’t it? Maybe it’s not quite that simple.

I’d argue we need to look at the bigger picture, the context these people lived in and the other elements of the burial. And that context screams *water*.

Water: Lifeblood and Afterlife

The Tarim Basin rivers, fed by mountain meltwater, created the oases that made life possible for the Xiaohe people. Water wasn’t just a resource; it was the foundation of their existence. They relied on it for agriculture (wheat, millet) and for their cattle. The archaeological record shows evidence of both water-loving plants like reeds and desert-adapted plants, highlighting their connection to this dual environment.

Considering this deep reliance on a riverine environment, let’s revisit those “boat-shaped” coffins. Some researchers have pointed out they look less like boats and more like *upturned canoes*. And the poles? If the coffin is a vessel, what could those poles be? The ones with broad endings look an awful lot like paddles. And the posts sometimes found at the other end? They could be interpreted as mooring posts, like those used to tie up a boat.

Think about it: a culture living by rivers, burying their dead in what look like upturned canoes, complete with symbolic paddles and mooring posts. It paints a powerful picture, doesn’t it? It suggests a conceptualization of death as a journey, a voyage across water, much like the boat burials found in other Bronze Age cultures across the world, from Scandinavia to Egypt. It’s not necessarily about direct contact between these places, but perhaps a shared human idea about transition.

The Upside-Down World

Here’s where it gets really intriguing. The boat-shaped coffins are *intentionally* turned upside down. The paddles, if that’s what they are, point upwards. It’s as if the burial ritual is happening on the underside of a surface. The sand-filled pit becomes the ‘water,’ and the emerging paddle or mooring post breaks the ‘surface’.

This intentional inversion strongly suggests that the Xiaohe people might have conceived of the otherworld as a mirrored realm of the living world, separated by a reflective surface – perhaps the surface of the water that was so central to their lives. Just as their boats navigated the rivers and lakes in the physical world, these inverted vessels might have been meant to carry the deceased across the metaphorical waters of the afterlife. It’s a powerful visual metaphor, linking life, death, and the essential element of water.

This idea of an inverted otherworld isn’t unique to Xiaohe, either. We see similar concepts in ancient Egyptian texts, Saharan rock art, and even in the Great Basin. It seems to be a recurring human notion, perhaps particularly resonant in arid environments where water is both precious and transformative.

Piecing Together the Symbols

While we can never truly know the full cosmological views of the Xiaohe people, looking at their symbols – the boat-shaped coffins, the paddles, the mooring posts, the central role of cattle, and the intentional inversion – through the lens of their environmental context, particularly their deep connection to water, offers a compelling interpretation.

It moves beyond trying to decode symbols as simple tokens for social status or gender and instead sees them as part of a richer cultural narrative about life, death, and the journey between worlds. Water was essential for their survival, shaping their economy and likely their social structures. It makes sense that this vital element would also shape their understanding of the intangible realm of death.

Of course, interpreting symbols from prehistory is always a delicate dance. We have to be cautious and acknowledge the fluidity and potential ambiguity of meaning. But the exceptional data from Xiaohe gives us a much better starting point than most other sites.

The Xiaohe burials are more than just fascinating archaeological finds; they’re a window into how a unique Bronze Age culture, intimately tied to its riverine environment, might have envisioned the transition from this world to the next. It’s a story told in upturned boats, silent paddles, and the ever-present echo of water in the desert sand.

Source: Springer