Toxoplasmosis: Unmasking the Inner Workings with Math Models (Free Parasites Edition!)

Hey there, fellow science explorers! Ever thought about what happens when a tiny, uninvited guest like a parasite sets up shop inside a host? It’s a microscopic drama, and today, we’re going to peek behind the curtain using the cool lens of mathematics. We’re diving into the world of toxoplasmosis, specifically looking at what happens within the host when those pesky free parasites are roaming around. Grab your thinking caps, because it’s about to get fascinating!

So, What’s This Toxoplasmosis Thing Anyway?

Toxoplasmosis is an infection caused by a single-celled protozoan parasite called Toxoplasma gondii. And let me tell you, this little critter is a world traveler! It can infect a huge range of hosts, including pretty much all mammals (yep, that includes us humans!) and birds. It’s estimated that about one-third of humankind has been exposed to it. In the USA alone, around 1.1 million people might get infected each year.

Now, for most folks with a strong immune system, the infection often goes into a latent phase, meaning it’s there, but not causing active mayhem. Tissue cysts can form, often in the muscle and brain. Usually, it’s asymptomatic, but sometimes, severe disease can pop up. There’s even research suggesting that latent toxoplasmosis might mess with human behavior or be linked to neurological issues like schizophrenia. And, a big concern is toxoplasmosis during pregnancy, as it can harm the developing fetus. Serious illness is mostly seen in congenitally infected children or people with weakened immune systems.

We do have drugs to treat active Toxoplasma infections, but they’re not great for the persistent, latent kind, can have nasty side effects, and aren’t always well-tolerated. Plus, drug resistance is becoming a thing. It’s not just a human problem either; toxoplasmosis can cause serious issues in animals, like abortions in sheep and goats, and severe illness in pets like cats and dogs, especially if they have other infections.

The Complicated Life of Toxoplasma gondii

Domestic cats and their relatives (Family Felidae) are the main hosts where T. gondii can complete its sexual life cycle. Most other warm-blooded animals, including us, act as intermediate hosts, where the parasite has an asexual cycle. Interestingly, T. gondii is “facultatively heteroxenous,” meaning it can complete its life cycle even without infecting other warm-blooded animals if it needs to.

Transmission happens in a few ways:

- Through contaminated feces (think cat litter).

- By eating raw or undercooked meat containing tissue cysts.

- Congenitally, from mother to fetus.

When an infected cat poops out oocysts, these can contaminate the environment. After a few days, these oocysts sporulate and become infectious. If another animal ingests these, they get infected. These oocysts are tough little cookies and can survive in soil or water for up to a year!

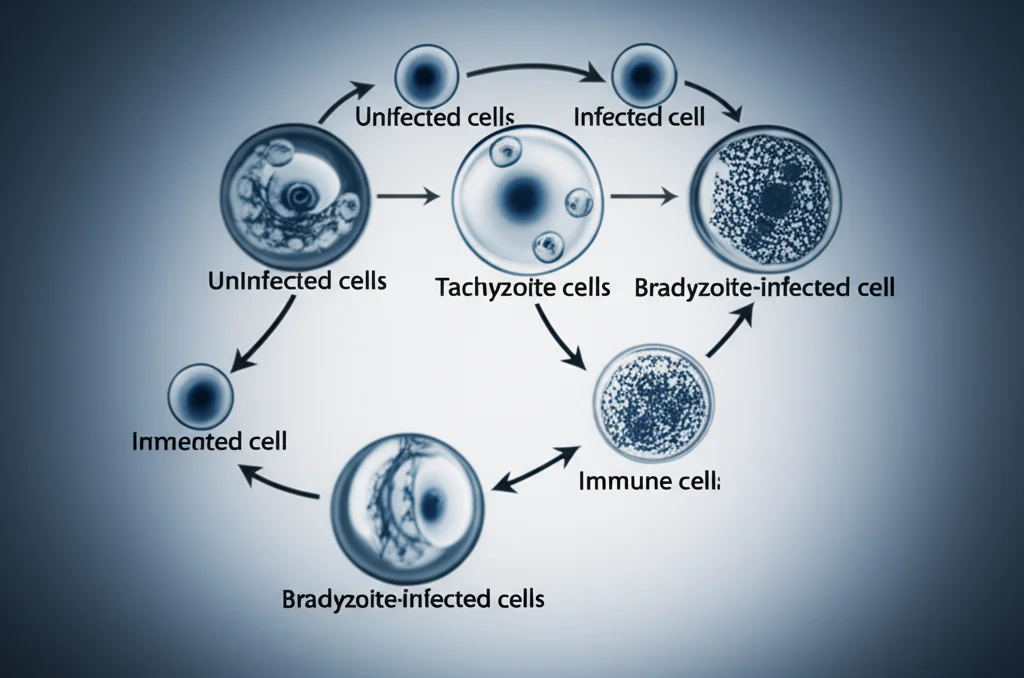

Inside the intermediate host, we mainly see two forms of the parasite:

- Tachyzoites: These are the fast-replicating ones. They invade cells and multiply like crazy (using a cool process called endodyogeny where two daughter parasites grow inside the parent, eventually consuming it). When the host cell is full, it bursts, releasing more tachyzoites to infect new cells. This is the acute phase of infection.

- Bradyzoites: These are the slow-growing, encysted form. In hosts with good immunity, most tachyzoites are wiped out, but some convert into bradyzoites, forming tissue cysts. This is the latent phase, allowing the parasite to persist. If these bradyzoites reactivate and turn back into tachyzoites, severe infection can re-emerge.

The journey starts when a host ingests either oocysts or meat with bradyzoite-filled cysts. If it’s cysts, digestive enzymes break down the cyst walls, releasing bradyzoites. These hardy bradyzoites invade intestinal cells and transform into tachyzoites. If it’s oocysts, sporozoites are released, invade intestinal cells, and then differentiate into tachyzoites. These tachyzoites then spread throughout the body via the bloodstream, ready to invade any nucleated cell. It’s a sneaky parasite, carefully triggering and evading the immune response to maintain a persistent infection.

Why Bring Math into This Biological Brouhaha?

You might be wondering, “Math? For parasites?” Absolutely! Mathematical modeling has become a super important tool in understanding how infections spread and progress. We’ve seen it used for everything from predicting epidemics (like the recent COVID-19 pandemic) to evaluating control strategies. These models can look at interactions from the micro-level (host-pathogen) to the macro-level (host-to-host), and even include ecological or economic factors.

While there’s been a lot of experimental research on Toxoplasma gondii, mathematical modeling studies are a bit more limited, especially for what’s happening inside the host. Some previous studies have used ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to model toxoplasmosis in human and cat populations, and a few have even looked at time delays. It’s been argued that these within-host processes are linked to how the parasite transmits between hosts. Some models have even coupled within-host and between-host dynamics, revealing complex behaviors like backward bifurcations (where an infection can persist even if the basic reproduction number is less than one – yikes!).

The cool thing about within-host models is they can help us understand the nitty-gritty details, like how fast parasites invade cells, replicate, or switch between their tachyzoite and bradyzoite forms. For example, some research showed that the invasion process by T. gondii happens in just a few minutes, while replication and stage transition take hours.

Our Study: Zooming in on Free Parasites

So, what’s new with our work? We’re taking a closer look at mathematical models that describe the parasite dynamics *inside* a host, specifically focusing on the role of free parasites – those tachyzoites and bradyzoites that are out and about, not yet inside a cell.

Previous work, like a model introduced in a 2004 study by Fefferman et al., sometimes simplified things by assuming that these free parasites move and infect so quickly compared to other processes (like cell infection and parasite replication) that their numbers could be considered to be in a “steady state.” Think of it like a very fast-flowing river – the amount of water passing a point at any given moment is roughly constant, even though individual water molecules are zipping by.

In our study, we decided to tackle two models:

- The first model is based on that steady-state assumption for free parasites. This simplifies things down to a 5-dimensional system of equations.

- The second, more complex model, doesn’t make that assumption. It explicitly considers the dynamics of free bradyzoites and free tachyzoites, leading to a beefier 7-dimensional system.

Our main goal was to do a detailed stability analysis for both. This means we’re trying to figure out the long-term behavior of the infection. Will the parasite die out? Will it persist at some level? And how does the presence (or non-steady state) of free parasites affect these outcomes? We’re talking about equilibrium points (like a disease-free state or an endemic state where the infection hangs around) and their stability. We also calculated the famous basic reproduction number (R0 or R3 in our case) for each model. This number basically tells us, on average, how many new infections one infected “unit” (in this case, perhaps an infected cell or a free parasite leading to an infected cell) can cause in a completely susceptible population. If it’s less than 1, the infection should die out. If it’s greater than 1, it can spread.

Model 1: Free Parasites on Cruise Control (Steady State)

Alright, let’s get into our first model. This one, as I mentioned, assumes that free tachyzoites (PT) and free bradyzoites (PB) are in a steady state because their dynamics are super fast. The model keeps track of:

- Uninfected cells (X)

- Cells infected with tachyzoites (YT)

- Cells with early-stage bradyzoites (YC)

- Cells with encysted bradyzoites (YB)

- The host’s immune effector cells (Z)

The infection rates depend on constants (beta_T) and (beta_B), which are derived from the original infection rates by free parasites and their clearance rates. We crunched the numbers and found the basic reproduction number for this model, which we’ll call ({mathcal {R}}_0).

Stability in Model 1: What Happens in the Long Run?

Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE): This is the happy state where there’s no infection. We found that if ({mathcal {R}}_0 < 1), this DFE is not just locally stable (meaning small disturbances won't knock it off course) but globally asymptotically stable. In plain English, if the conditions are such that ({mathcal {R}}_0) is less than one, the infection will eventually die out, no matter how it started. We even used a nifty mathematical tool called a Lyapunov function to prove this global stability. Pretty neat, huh?

Endemic Equilibria (Infection Persists): Now, what if ({mathcal {R}}_0 > 1)? Things get a bit more interesting. We found two potential endemic equilibrium points, let’s call them E1 and E2.

- E1: This is an endemic state without an immune response (Z=0).

- E2: This is an endemic state with an active immune response (Z > 0).

The stability of these points depends on another factor: the difference between the immune system’s effector cell production rate ((rho)) and its clearance/death rate ((delta)), so (rho – delta). And also on another threshold, ({mathcal {R}}_1), which is a bit more complex but involves parameters like (delta), (h) (a saturation constant for immune response), and the infection/conversion rates.

Here’s a quick rundown of what we found for Model 1 when ({mathcal {R}}_0 > 1):

- If (rho – delta le 0) (immune response production doesn’t outpace its decay): Only E1 (no immune response) exists and is globally asymptotically stable. So, the infection persists, but the specific immune cells we modeled eventually fade away.

- If (0 < {mathcal {R}}_1 < rho – delta) (stronger potential immune buildup): Both E1 and E2 can exist. Here, E1 (no immune response) becomes unstable, and E2 (with immune response) is locally asymptotically stable. This means the system tends towards a state where the infection persists alongside an active immune response.

- If (0 < rho – delta < {mathcal {R}}_1) (moderate potential immune buildup): Only E1 exists (E2 isn’t biologically feasible as Z would be negative) and is locally asymptotically stable. So, infection persists, but the immune response (Z) doesn’t establish.

We backed all this up with numerical simulations, playing around with parameter values to see if our math matched what the computer showed. And guess what? It did! For example, when we set parameters so ({mathcal {R}}_0 1) and (rho < delta), the system settled into the E1 state. It’s always a good feeling when the theory and simulations shake hands!

Model 2: Unleashing the Free Parasites (Not in Steady State)

Now for the main event, at least for me! This is where we let the free tachyzoites (PT) and free bradyzoites (PB) have their own dynamic equations. No more assuming they’re in a steady state. This makes the model more complex (7 equations now!), but potentially more realistic for certain scenarios. The state variables are:

- Uninfected cells (X)

- Tachyzoite-infected cells (YT)

- Early-stage Bradyzoite-containing cells (YC)

- Encysted-Bradyzoite-containing cells (YB)

- Free tachyzoites (PT)

- Free bradyzoites (PB)

- Host’s immune system’s effector cells (Z)

We again calculated a basic reproduction number for this model, let’s call it ({mathcal {R}}_3). This one involves the rates at which free parasites are produced (kT from YT, kC from YC) and their clearance rates (uT, uB), along with the infection probabilities ((beta_{PT}), (beta_{PB})).

Stability in Model 2: The Full Picture

Disease-Free Equilibrium (DFE): Just like before, if ({mathcal {R}}_3 < 1), the DFE is globally asymptotically stable. So, if the conditions don’t favor the parasite’s spread (considering the full dynamics of free parasites), the infection clears out. We used a comparison theorem to show this, which is another cool mathematical trick.

Endemic Equilibria (When Infection Persists with Dynamic Free Parasites): When ({mathcal {R}}_3 > 1), we again found two potential endemic steady states, which we’ll also call E1 (no immune response, Z=0) and E2 (with immune response, Z > 0), but their mathematical expressions are now based on the parameters of this 7-dimensional model.

The stability story here also depends on (rho – delta) and a new threshold, ({mathcal {R}}_2), which is analogous to ({mathcal {R}}_1) but for this more complex model.

Here’s the gist for Model 2 when ({mathcal {R}}_3 > 1):

- If (rho – delta le 0): Only E1 (no immune response) exists and is globally stable. The infection persists, immune cells (Z) die out, and free parasites are part of this dynamic equilibrium.

- If (0 < rho – delta < {mathcal {R}}_2): Only E1 exists (E2 is not biologically feasible) and is locally asymptotically stable. Again, infection persists, but the specific immune response modeled doesn’t take hold, even if its production rate is slightly higher than its decay.

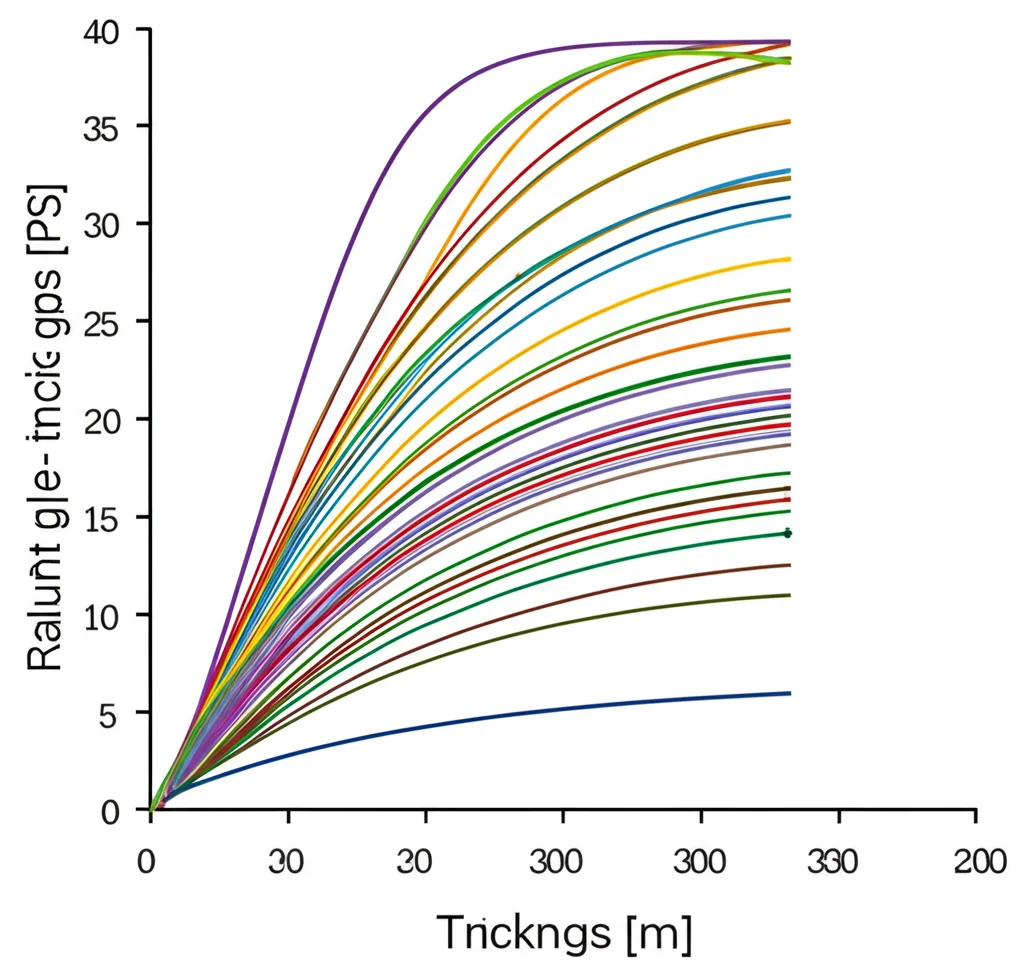

- If (0 < {mathcal {R}}_2 le rho – delta): This is the most intriguing case! Both E1 and E2 can exist. E1 (no immune response) becomes unstable. However, E2 (with immune response and dynamic free parasites) is locally asymptotically stable. Our numerical simulations strongly suggest it might even be globally stable in this scenario. This means the system prefers a state where the infection, the free parasites, and the immune response all coexist.

We ran simulations for this model too. For instance, when ({mathcal {R}}_3 1) and we had the (0 < {mathcal {R}}_2 le rho – delta) condition, starting near the unstable E1 point made the system move towards the stable E2 point. This is super interesting because it shows how the interplay between parasite dynamics and immune response can lead to different long-term outcomes.

What’s the Big Takeaway?

So, what did we learn from all this mathematical wrangling? Well, for starters, the presence and dynamics of free parasites definitely matter! Both models showed that the basic reproduction number (({mathcal {R}}_0) or ({mathcal {R}}_3)) is key: if it’s below 1, the parasite is likely toast. If it’s above 1, the infection tends to stick around.

A really crucial finding, consistent across both models, is how important the balance between the immune system’s effector cell production rate ((rho)) and its removal/decay rate ((delta)) is.

- If the removal rate is higher or equal to the production rate ((rho le delta)), and infection is established ((R_0 > 1) or (R_3 > 1)), we generally see only one stable endemic state where the specific immune cells (Z) we modeled are absent.

- However, if the production rate is higher ((rho > delta)), things get more complex. We can have scenarios with two endemic points, one stable (with an active immune response, Z > 0) and one unstable. The exact outcome depends on those other thresholds (({mathcal {R}}_1) or ({mathcal {R}}_2)).

The model that explicitly included free parasite dynamics (Model 2) gave us a more detailed picture. The scenario where (0 < {mathcal {R}}_2 le rho – delta) was particularly fascinating, suggesting a stable coexistence of uninfected cells, various infected cell types, free parasites, and an active immune response. This seems like a more realistic long-term picture for a persistent infection like toxoplasmosis.

Of course, these models are simplifications. The real world is always more complicated! For example, we didn’t consider how the immune system might affect the conversion between tachyzoites and bradyzoites, or that encysted bradyzoites might arise from sources other than tachyzoite-infected cells. Also, some parameter values are hard to pin down without very specific experiments. But that’s the beauty of modeling – it gives us a framework to understand the key drivers and points to where more experimental research could be super valuable, especially on those immune response rates!

Where Do We Go From Here?

This work opens up avenues for future research. Proving global stability for all scenarios (especially for that E2 point in Model 2) would be a cool mathematical challenge, likely requiring some clever Lyapunov functions. We could also make the models even more detailed, perhaps including how immunity affects parasite stage conversion.

And the big dream? Integrating these within-host dynamics with between-host transmission models. That would be an extraordinary challenge but could give us an even more complete understanding of toxoplasmosis. We could also explore things like fractional derivatives for memory effects, time delays in processes, or even control strategies to reduce infection.

So, while we’ve been wrestling with equations, it’s all to get a better handle on this widespread and sometimes sneaky parasite. Math, it turns out, is a pretty powerful microscope for looking at the hidden battles happening inside us!

Source: Springer