The Secret Life of Water: How Tiny Surfaces and Molecular Wiggles Control Ice

Okay, so let’s talk about ice. Not the stuff in your freezer (though this is related!), but how ice *starts* forming, especially on surfaces. You know how sometimes you get frost on heat exchangers, or those phase change materials (PCMs) for energy storage don’t freeze quite right? A lot of that comes down to something called ice nucleation – basically, the very first steps of ice crystal formation at the molecular level.

Turns out, the surface where water meets something solid plays a huge role. We’ve known that for a while. But lately, scientists have been getting curious about something else: the water itself. Not just its structure, but how the molecules are *moving*. It’s a bit like a tiny, invisible dance floor where some water molecules are zipping around, and others are just kinda… chilling. This is called dynamical heterogeneity (DH).

So, I was looking at this really neat study that used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to dive deep into this. They wanted to see how the movement of water molecules right next to a surface affects where and when ice decides to pop into existence. They simulated water on a perfect platinum surface and also on one with tiny, nanometer-scale slits. Pretty cool, right?

The Tiny Dance of Water and Why It Matters

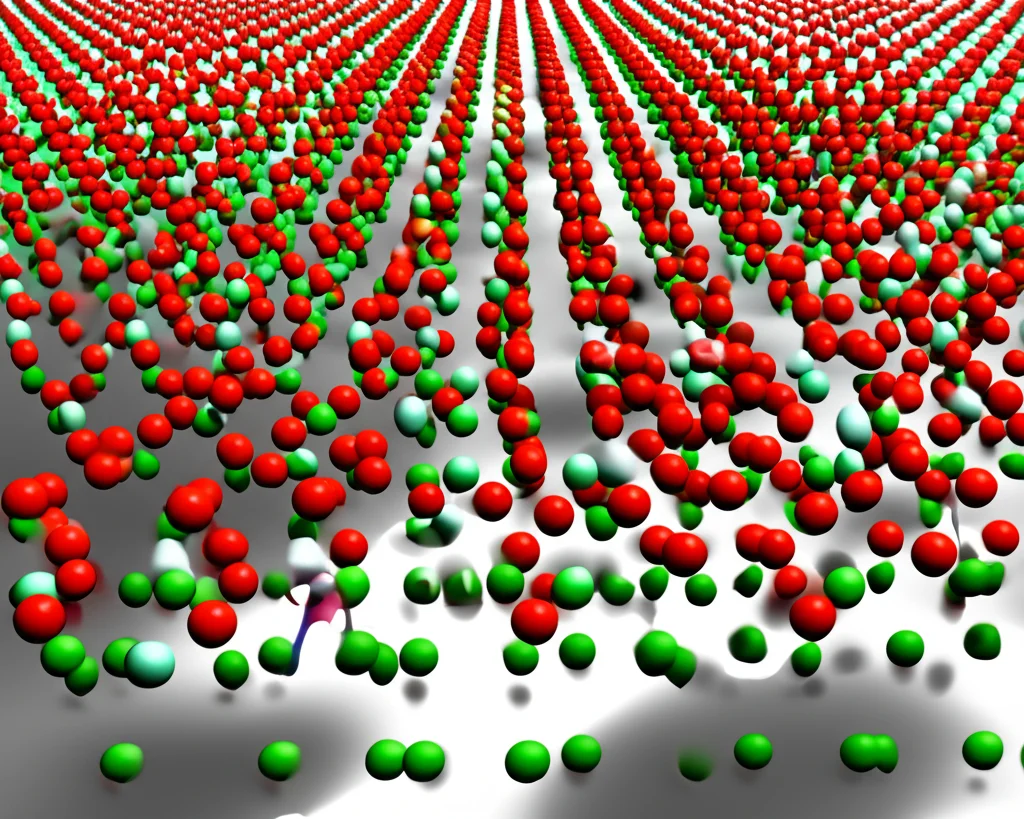

Imagine water molecules in a supercooled state (liquid below its normal freezing point, just waiting for an excuse to solidify). They aren’t all moving at the same speed. Some are faster, some slower. This DH is a known thing, especially in liquids near their glass transition point (where they get really thick and slow). Researchers have suspected this might influence ice nucleation.

To measure this “speed” or mobility at a local level, the study used something called Local Diffusivity (LD). Think of LD as a way to quantify how much a tiny group of water molecules is jiggling around in a specific spot over a very short time. It’s an indicator of that dynamic heterogeneity.

Previous work had hinted that homogeneous ice nucleation (ice forming in the middle of the water, away from surfaces) was more likely in regions where molecules were moving *slower* (low mobility). This study wanted to see if the same held true for heterogeneous ice nucleation – ice forming *on* a solid surface.

Flat Surfaces: Where Ice Likes to Start (and Where It’s Slow)

First, they looked at a flat, perfect platinum surface. They even tweaked the surface to be slightly more ‘water-attracting’ (hydrophilic) or more ‘water-repelling’ (hydrophobic) by changing the interaction strength between the platinum and water molecules. They measured the contact angle – how a water droplet would spread out – to confirm this: about 80 degrees for hydrophilic, 110 degrees for hydrophobic. As expected, ice formed faster on the more hydrophilic surface (average 5.6 ns vs. 105.7 ns for hydrophobic). Lower wettability means slower freezing.

But the real kicker was looking at *where* the ice started. They tracked the very first “critical nucleus” – the tiny ice cluster that’s stable enough to grow irreversibly. Turns out, on the flat surfaces, these critical nuclei consistently formed in areas where the water molecules had relatively low LD. Yes, the slower-moving spots!

This tendency was even *more* pronounced on the hydrophobic surface. Why? Probably because the water molecules near the hydrophobic surface were already moving faster overall (less “stuck” to the surface), so the contrast between the fast and slow regions was greater, making those slow spots stand out as prime nucleation sites.

Adding Texture: The Slit Story

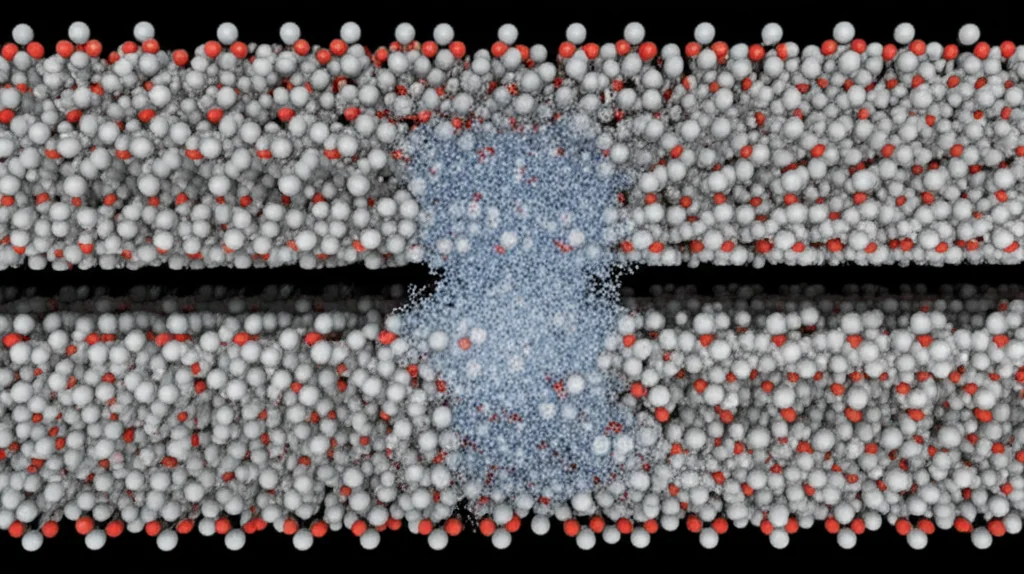

Next, they introduced a twist: a surface with tiny, rectangular slits carved into it. They focused on one specific slit width initially (about 2.77 nm). The solid-liquid interaction strength was kept the same as the hydrophilic flat surface.

Interestingly, ice nucleation on this slit surface was *slower* than on the flat hydrophilic surface (average 45.5 ns vs. 5.6 ns). This suggests the slit structure, under these conditions, actually *inhibits* ice formation compared to a smooth, water-attracting surface. And get this – the critical nuclei *avoided* forming directly over the slit structure itself. They preferred the flat ‘substrate’ areas between the slits, and even there, they tended to form away from the slit walls.

Slits and LD: A Different Relationship

They also looked at the LD distribution on the slit surface. Near the substrate areas, the LD values were actually *lower* than on the flat hydrophilic surface, likely because the side walls of the slits had some subtle effects on water adsorption. When they checked the correlation between low LD regions and where critical nuclei formed on the substrate areas, they still found a tendency for nucleation in slower spots, but it wasn’t as strong as on the flat surfaces.

The researchers figure this weaker correlation might be because the water molecules’ structure and movement are more complex and varied near the slit walls compared to a simple flat surface. The structural variations might be competing with the dynamic (LD) influence on nucleation location.

Size Matters: The Slit Width Saga

This is where it gets really fascinating. They didn’t stop at one slit width. They tested surfaces with various slit widths, keeping the overall system size and slit height the same. And they found that the *width* of the available space – either the width of the slit itself or the width of the flat substrate area between slits – had a big impact on how fast ice formed.

- When either the slit or the substrate area was relatively *large*, nucleation happened faster.

- When the spaces were relatively *narrow*, nucleation took longer.

Why? The study suggests it’s about having enough room for the ice nucleus to grow to its critical size. They found that the critical nucleus size was around 50 water molecules, which corresponds to a physical size of about 2 nm in the x-y plane. If the flat area (either the slit or the substrate) is too narrow – say, less than that critical size – the growing ice cluster bumps into the side walls and its growth gets hindered. It might just shrink and disappear before it can become a stable, irreversible nucleus.

So, it’s like trying to build a big sandcastle in a tiny sandbox. You just don’t have enough room for it to reach that stable size where it won’t collapse. The simulations showed examples of ice nuclei starting to grow in narrow areas, hitting the “walls” of the slit structure, and then failing to reach the critical size and eventually vanishing.

Putting It All Together

This study gives us some pretty cool insights into the microscopic world of ice formation on surfaces. We learned that:

- Water molecules in supercooled liquid aren’t uniform; they have regions of different mobility (DH).

- On flat surfaces, ice tends to start in the spots where water molecules are moving slower (low LD). This is similar to what’s seen in homogeneous nucleation.

- Adding nanostructures like slits can inhibit nucleation compared to a flat, water-attracting surface.

- Nucleation tends to avoid the slit structures themselves under these conditions.

- While low-LD regions are still preferred nucleation sites on the substrate areas of the slit surface, the correlation isn’t as strong as on flat surfaces, possibly due to structural variations near the slits.

- Crucially, the *width* of the available flat space (either the slit or the substrate) matters a lot. If it’s too narrow to accommodate the growth of the critical ice nucleus (around 2 nm), nucleation is significantly delayed or inhibited.

This isn’t just academic curiosity. Understanding these fundamental processes at the molecular level could help us design better surfaces to control frost formation on things like air conditioners or improve the performance of PCMs by controlling when and how they solidify. It’s all about manipulating that tiny dance of water molecules and the surfaces they interact with.

Conclusion

So there you have it – a peek into how the dynamic properties of water and the geometry of surfaces at the nanoscale team up to dictate the tricky business of ice nucleation. It’s a complex interplay, but studies like this using powerful simulations are helping us unravel the secrets of water’s frozen beginnings.

Source: Springer