Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Why Scaling Parameters Isn’t a Simple Fix

Hey folks, let’s dive into something super interesting (and maybe a little frustrating!) about how we try to use cool tech like Vagus Nerve Stimulation, or VNS for short, to help people. You see, VNS shows amazing promise in animal studies for all sorts of things – stroke recovery, heart failure, even inflammation. It’s like a magic wand for the nervous system! But here’s the rub: when we try to take those exact same settings that worked wonders in, say, a rat, and use them in a human patient… well, things often don’t quite pan out the way we hoped.

The Translation Problem

It turns out, getting VNS therapies from the lab bench (preclinical studies, usually in animals) to the clinic (human patients) is a real challenge. A big part of the puzzle seems to be how we pick the stimulation parameters – things like the strength and timing of the electrical pulses. Historically, we haven’t really accounted for how different individuals, or even different species, might respond uniquely to the same zap. This lack of tailored parameter selection could be a major reason why those super promising animal results don’t always show up in human trials.

Think about it: if the goal is to activate a specific group of nerve fibers to get a therapeutic effect, but the same electrical pulse activates completely different fibers (or none at all!) in a human compared to a rat, you’re probably not going to get the same outcome. We need to get smarter about how we translate these therapies.

Why Scaling Isn’t Simple: It’s About Morphology!

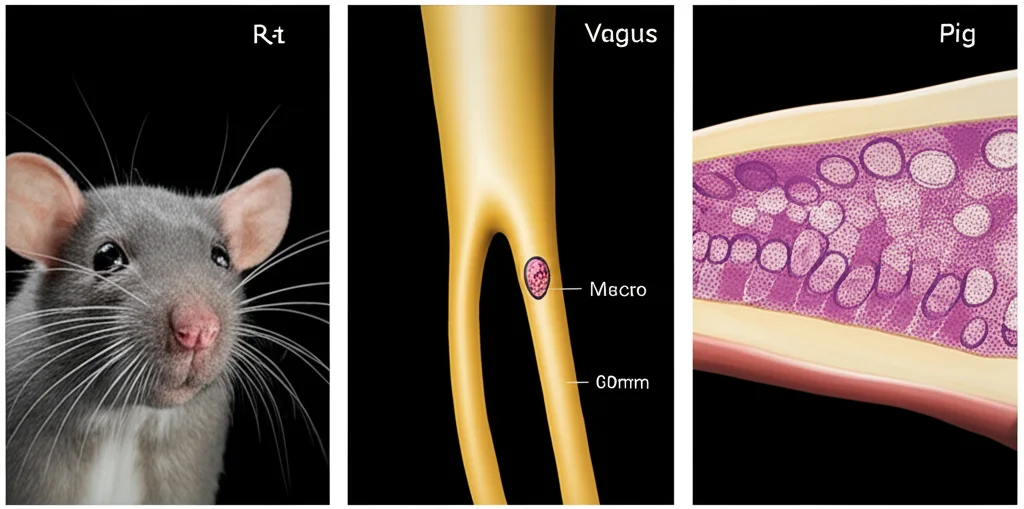

So, why the big difference in response? A huge factor is the actual physical structure, or morphology, of the vagus nerve itself. Just like people look different, the vagus nerve looks different across species, and even between individuals of the same species!

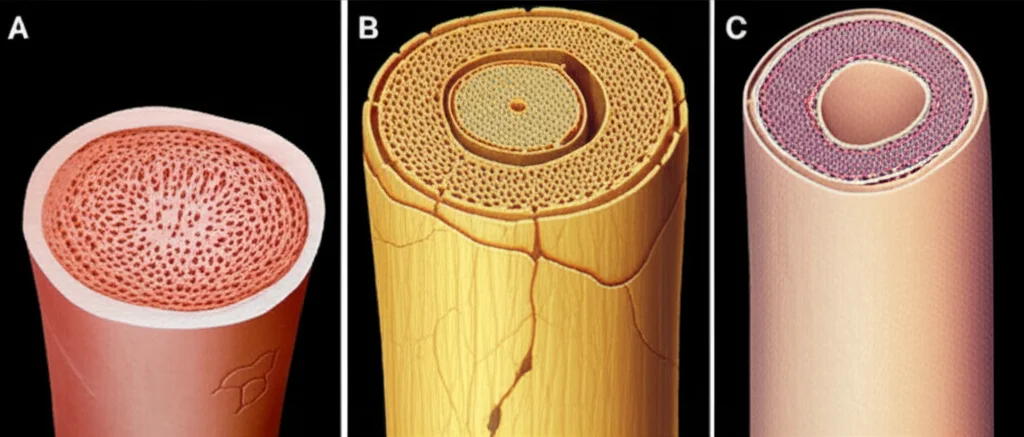

For example, human and pig vagus nerves are about 10 times bigger than rat vagus nerves. And it’s not just size; the internal structure varies wildly too. Rats typically have one main bundle of fibers (a fascicle), while pigs can have around 47, and humans average about 7, but with a lot more variability in their size and arrangement. These differences in nerve size, the number and size of fascicles, and even the thickness of the protective sheath around the nerve bundles (the perineurium) all affect how the electrical stimulation spreads and which fibers get activated.

Historically, when translating VNS from animals to humans, we’ve often just “recycled” the parameters – using the exact same stimulation intensity. Or, maybe we’ve tried a simple “linear scaling,” just multiplying the animal dose by some factor. But as we’re finding out, that’s like trying to use the same key to open completely different locks.

Modeling the Nerve Response

To really understand this, we used some pretty sophisticated tools: computational models. Imagine building detailed virtual replicas of the vagus nerve based on real anatomical data (histology) from humans, pigs, and rats. We used models built with a platform called ASCENT, incorporating individual nerve structures from nine humans, twelve pigs, and nine rats. We even modeled the different types of electrodes used in studies – the standard clinical helical cuff for humans and pigs, and a different bipolar cuff often used in rat studies.

With these models, we could simulate what happens when you apply electrical pulses (specifically, biphasic rectangular pulses of different durations: 0.13, 0.25, and 0.5 milliseconds). We could calculate the exact amount of electrical current needed to activate different types of nerve fibers: the fast A-fibers (often associated with side effects like throat muscle activation), the medium B-fibers (often linked to therapeutic effects like heart rate changes), and the slow C-fibers.

We also defined a “K” ratio – basically, a scaling factor representing the ratio of activation thresholds between any two individuals or species. This let us quantify just how much the required stimulation amplitude varied.

What the Models Showed: Variability is Key

The results from these models were eye-opening, but perhaps not surprising given the anatomical differences.

First off, even within the *same* species, applying the same VNS parameters produced a *large range* of nerve responses. This is because of those individual differences in nerve morphology. What activates 50% of the target fibers in one person might activate only 10% or maybe even 90% in another!

When we looked across species, the picture got even more complicated. Applying the same stimulation amplitudes from one species to another produced *highly variable* responses. For instance, the current needed to activate fibers in humans and pigs was typically 10 to 100 times higher than in rats! There was very little overlap in the required amplitudes between rats and the larger species.

We calculated those “K” ratios (the scaling factors) between species, and wow, they spanned a huge range. Trying to scale from smaller to larger species required much bigger factors for B fibers than for A fibers, and the factors changed depending on the pulse width. This means a simple linear scaling factor just doesn’t cut it if you want to achieve an equivalent nerve response.

Even when we tried scaling using the *average* K ratio between species, we still saw massive variability in the resulting nerve activation across individuals in the target species. The average might hit the mark, but for any given individual, the response could be anywhere from almost nothing to activating *all* the fibers!

The variability within a species (how much individuals differ) also contributes to the difficulty of scaling between species. Humans and pigs, with their more complex and variable nerve structures, showed much greater within-species variability in the required stimulation amplitudes compared to rats, whose simple, monofascicular nerve structure results in much less individual difference. This might mean that preclinical studies in rats, while valuable, don’t fully prepare us for the anatomical variability we’ll encounter in humans.

Real-World Examples: Stroke, Heart Failure, Inflammation

This research helps explain why some VNS clinical trials haven’t replicated the success seen in animals.

* Stroke Recovery: In rat studies, VNS plus rehab led to great recovery. The parameters used (0.8 mA, 0.1 ms pulse) were simply “recycled” for human trials. Our models showed these parameters activated both A and B fibers in rats. But in humans, the same parameters primarily activated A fibers (leading to side effects like throat muscle activation, which limited the amplitude) and often *didn’t* activate the B fibers thought to be important for the therapeutic effect. It’s less surprising, then, that only about half of human patients saw significant improvement compared to almost all rats.

* Heart Failure: Animal studies (rats, canines) showed VNS consistently caused bradycardia (slowing heart rate), indicating B fiber activation, and had therapeutic benefits. Clinical trials, despite using much higher amplitudes (20-40 times higher than rats!), often failed. Patients were limited by A fiber side effects before reaching amplitudes needed for consistent B fiber activation. Our models predicted that humans might need amplitudes 30-100 times higher than rats for B fiber activation, highlighting the massive scaling challenge.

* Inflammation: Parameters used in human trials (1 mA, 0.5 ms pulse) were similar to the *highest* amplitudes used in effective rat studies (0.25 and 0.5 mA were effective, 0.1 and 1 mA were not). Our models suggest the effective rat parameters (0.25, 0.5 mA) activated A and B fibers, and potentially C fibers at 0.5 mA. The human parameters activated A fibers and B fibers in some individuals, but not C fibers. This suggests that maybe activating fibers with excitability closer to C fibers is needed for the full anti-inflammatory effect, and the standard human parameters weren’t achieving that consistently across individuals.

Essentially, recycling parameters across species completely ignores the vast differences in nerve morphology. Even simple linear scaling isn’t enough because the *variability* within species makes a single scaling factor unreliable for any given individual.

The Path Forward: Tailoring VNS

So, what do we do? The big takeaway is that we desperately need systematic ways to select VNS parameters that account for these individual and species-specific differences in nerve response. Simply scaling or recycling parameters isn’t working.

Computational models, like the ones used in this study, are incredibly valuable tools here. They can help us predict what stimulation parameters are needed to achieve a *targeted* nerve response (activating specific fiber types) based on the known morphology.

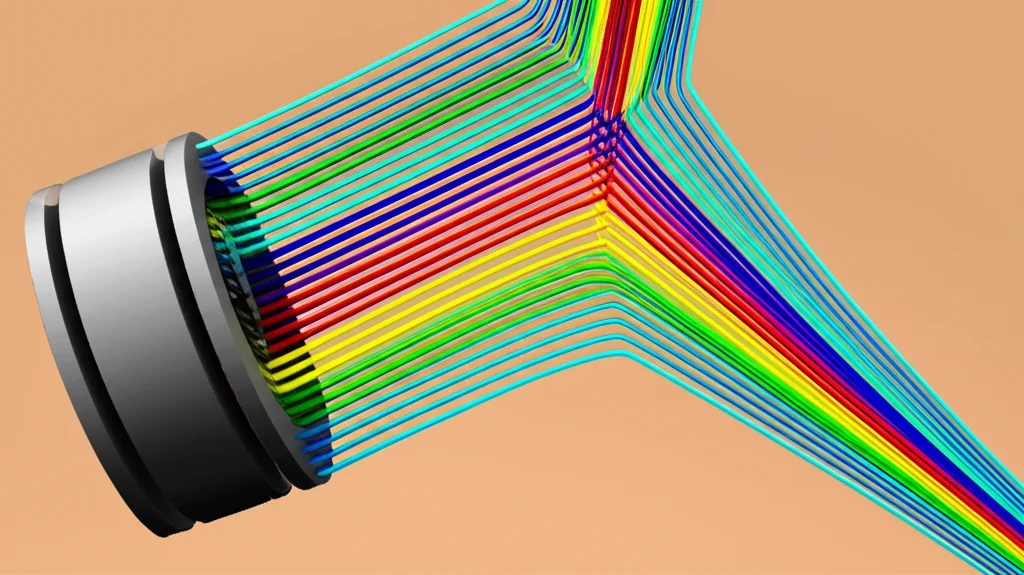

To make this truly personalized for patients, we need advances in technology. Imagine being able to image a patient’s vagus nerve in detail *in situ* (while it’s still in their body) to understand its unique structure and how the fibers are arranged. This kind of data could feed into patient-specific computational models to determine the optimal stimulation settings or even help design better electrodes.

We could also get smarter about how we monitor responses. Instead of just looking for side effects, maybe we need ways to measure the actual nerve signals (like compound action potentials) evoked by stimulation to confirm we’re hitting the right target fibers.

Future VNS therapies will likely involve more than just picking a simple amplitude and pulse width. We might see:

- More advanced electrode designs (like multicontact cuffs) that allow for more precise targeting of specific nerve bundles.

- Sophisticated stimulation waveforms designed to selectively activate or block certain fiber types.

- Closed-loop systems that automatically adjust stimulation based on measured nerve activity or physiological responses.

The current practice of just increasing amplitude until side effects occur isn’t optimal because everyone’s nerve is different. What limits the dose in one person might not even activate the therapeutic fibers in another.

Ultimately, achieving consistent and effective VNS therapies means moving beyond one-size-fits-all approaches. We need to quantify and tune the nerve response for each individual patient, ensuring that the stimulation parameters produce the specific pattern of fiber activation required for therapy. It’s a complex challenge, but with tools like advanced computational models and future imaging tech, we’re getting closer to unlocking the full potential of VNS.

Source: Springer