The Colorectal Cancer Conspiracy: USP14, S100A11, and Stopping Cell Aging

Hey there! Let’s chat about something super important: colorectal cancer (CRC). It’s a big deal globally, and sadly, rates are climbing, especially in places like Asia. Now, cancer is sneaky; it’s not just one thing going wrong. It’s a whole mix of genetic glitches, changes in how genes are expressed, and even stuff happening with our gut bugs. Understanding *how* it starts and spreads is key to finding better ways to diagnose it, predict its path, and, most importantly, treat it.

We’ve seen some cool progress with targeted therapies lately. Think of drugs like cetuximab or panitumumab that go after specific targets on cancer cells, or bevacizumab which tries to cut off the tumour’s blood supply. And then there’s regorafenib for when standard treatments aren’t enough. These show us that finding specific molecular targets is a really promising route.

Meet the Players: S100A11 and USP14

So, in the vast world of proteins, there’s a family called S100 proteins. One member, S100A11, pops up in all sorts of cellular activities – like how cells grow, change, and move. But it’s also been spotted helping tumours grow and spread, particularly by helping cells change their form (a process called epithelial-mesenchymal transition, or EMT). We’ve seen S100A11 levels go up in lung, cervical, pancreatic, and yes, colorectal cancers, where it seems to give tumours a boost. It even hangs out with another protein called RAGE, which can make the area around the tumour inflamed and help cancer cells avoid dying.

Then there’s USP14. This guy is a bit of a cellular janitor, specifically a ‘deubiquitinating enzyme’. Think of ubiquitin as a little tag that tells proteins when it’s time to be broken down. USP14 removes this tag, essentially saving proteins from the cellular recycling bin. This can be good for normal cell health, but in cancer, it can help keep bad-guy proteins around longer, boosting tumour growth and survival. USP14 levels are high in several cancers, including CRC, breast, and liver cancers, where it helps cells grow and stops them from dying off. But how exactly it does its thing in CRC hasn’t been totally clear.

What We Found: S100A11 is Upregulated and Nasty

In this study, we dove deep into S100A11 in CRC. What we saw was pretty striking: S100A11 is definitely cranked up in clinical CRC samples, and higher levels seem to go hand-in-hand with more advanced stages of the disease. Data from big public databases (like TCGA and GEO) backed this up, showing higher S100A11 mRNA in CRC tissues. Looking at CRC cell lines in the lab, we also saw higher S100A11 protein compared to normal cells. Even single-cell data pointed to increased S100A11 in the actual malignant cells within a tumour. And the clincher? Patients with high S100A11 levels had worse survival outcomes. So, yeah, high S100A11 is linked to a poorer prognosis in CRC.

S100A11: Fuelling Cancer Growth and Spread

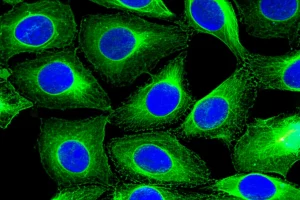

To figure out what S100A11 actually *does*, we tinkered with its levels in CRC cell lines. When we knocked down S100A11 (basically, reduced its amount), we saw the CRC cells slow down significantly. They didn’t proliferate as much, they weren’t as good at invading or migrating, and they were more likely to undergo apoptosis (cell suicide – a good thing when it comes to cancer!). We saw changes in proteins that control apoptosis, like an increase in BAK and a decrease in Bcl-2, FOXM1, and survivin. We also noticed shifts in proteins involved in that EMT process I mentioned – E-cadherin went up (which usually keeps cells together), while N-cadherin and Snail went down (these help cells become more mobile and invasive). Conversely, when we boosted S100A11 levels, the cells became more aggressive – growing faster, forming more colonies, and getting better at migrating and invading. This pretty clearly tells us S100A11 acts like an oncogene, pushing CRC forward.

We didn’t stop there. We also checked this out in a mouse model. When we injected mice with CRC cells where S100A11 was silenced, the tumours grew much slower and were smaller. But when we injected cells with *extra* S100A11, the tumours grew faster and were bigger and heavier. And for metastasis (the spread of cancer), silencing S100A11 led to fewer and smaller metastatic spots in the lungs, while overexpressing it caused a significant increase in lung metastases. So, S100A11 isn’t just messing with cells in a dish; it’s promoting tumour growth and spread *in vivo*.

The Senescence Connection: S100A11 Stops Cells From Aging

Now, here’s where it gets really interesting. We looked at which cellular pathways were associated with high S100A11 expression. One pathway that popped up was related to cellular senescence. What’s senescence? Think of it as a state where cells stop dividing permanently, often in response to stress or damage, like the kind that can lead to cancer. It’s like a built-in safety brake to stop potentially cancerous cells from multiplying. However, it’s a bit of a double-edged sword because these senescent cells can also release factors (called the SASP – senescence-associated secretory phenotype) that can actually *help* nearby cancer cells grow and spread.

Our findings suggest S100A11 is involved in *modulating* this process. When we knocked down S100A11, we saw an increase in proteins that are key players in triggering cell cycle arrest and senescence, like P16, P21, and the tumour suppressor P53. At the same time, SIRT1, which is known to *inhibit* senescence, went down. We also saw an increase in those pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, CXCL1, CCL5) that are part of the SASP when S100A11 was silenced. And the most direct evidence? Staining for a marker of senescence (beta-galactosidase) showed a higher percentage of senescent cells when S100A11 was knocked down. This tells us that S100A11 seems to be actively *preventing* cells from entering this senescent state, which is a key way it helps cancer cells keep dividing unchecked.

USP14 Enters the Scene: Stabilizing S100A11

Okay, so S100A11 is bad news and stops senescence. But how are its levels controlled? Remember USP14, the protein janitor? We suspected it might be involved with S100A11. And guess what? Our experiments showed that USP14 and S100A11 actually bind to each other inside the cell. They even hang out in the same cellular neighborhoods.

We then dug into *how* USP14 affects S100A11. It turns out USP14 doesn’t really change the amount of S100A11 mRNA (the genetic blueprint), but it *does* affect the S100A11 protein itself. When we blocked the proteasome (the cellular machine that breaks down proteins), S100A11 levels went up, suggesting S100A11 is normally degraded this way. Then, using a technique to track protein lifespan, we saw that when we knocked down USP14, S100A11 protein didn’t stick around as long – its half-life decreased. But when we added *more* functional USP14, S100A11 became more stable. A version of USP14 that couldn’t do its deubiquitinating job didn’t have this stabilizing effect. This strongly suggests that USP14 works by removing those ubiquitin tags from S100A11, saving it from being broken down by the proteasome.

To confirm this, we directly looked at S100A11’s ubiquitination status. Overexpressing functional USP14 significantly *reduced* the amount of ubiquitin attached to S100A11. Knocking down USP14, on the other hand, *increased* S100A11 ubiquitination. This was true in different cell types, including CRC cells. The more functional USP14 there was, the less ubiquitinated S100A11 was. This is pretty clear evidence that USP14 is a key enzyme that deubiquitinates and stabilizes S100A11 protein in CRC cells.

The USP14/S100A11 Axis: A Cancer Power Couple

So, we have USP14 stabilizing S100A11, and S100A11 promoting cancer growth and stopping senescence. Are they working together in a meaningful way? We tested this by knocking down USP14 and then adding S100A11 back in (overexpression). As expected, knocking down USP14 significantly slowed down CRC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion, and it increased cellular senescence. But when we overexpressed S100A11 *at the same time*, it partially *rescued* these effects. The cells started growing and moving a bit more, and senescence was less pronounced. This is strong evidence that USP14 is exerting its effects on CRC progression, at least in part, by stabilizing S100A11.

Interestingly, while S100A11 and USP14 protein levels correlate positively in CRC tissues (meaning they tend to be high together), their mRNA levels don’t seem to correlate. This reinforces the idea that USP14 is regulating S100A11 primarily at the *protein* level by preventing its breakdown, rather than affecting how much S100A11 is initially made.

Putting It All Together: A Potential New Target

Based on everything we found, here’s the picture: In colorectal cancer, USP14 levels are often high. High USP14 acts like a guardian for S100A11, removing the ubiquitin tags that mark it for destruction. This leads to higher levels of S100A11 protein. Elevated S100A11 then puts the brakes on cell senescence (that cellular aging process that can stop cancer cells) and instead pushes the cells to proliferate, migrate, and invade, driving tumour progression and metastasis. This USP14/S100A11 axis seems to be a pretty important pathway helping CRC grow and spread.

This is super exciting because it points to a potential new way to fight CRC. Since USP14 stabilizes S100A11, and both contribute to the disease, targeting either or both could be effective. USP14 inhibitors are already being explored in cancer therapy and have shown promise in CRC by slowing growth and making other treatments work better. Our findings add another layer, suggesting that part of *why* USP14 inhibitors might work is by allowing S100A11 to be degraded, thus re-activating senescence and slowing down the cancer.

Looking Ahead

In a nutshell, this study confirms S100A11’s role as a driver in CRC and, crucially, uncovers a novel partnership with USP14. This USP14-S100A11 interaction, by inhibiting cell senescence, appears to be a key mechanism promoting CRC progression. This is a big deal because it suggests that disrupting this specific interaction could be a promising therapeutic strategy. There’s definitely more work to be done, perhaps developing drugs that specifically target how USP14 and S100A11 interact. Also, understanding more about how S100A11 stopping senescence affects cancer’s response to existing treatments could open up new possibilities. It’s a complex puzzle, but finding pieces like the USP14/S100A11 axis brings us closer to better solutions for patients.

Source: Springer