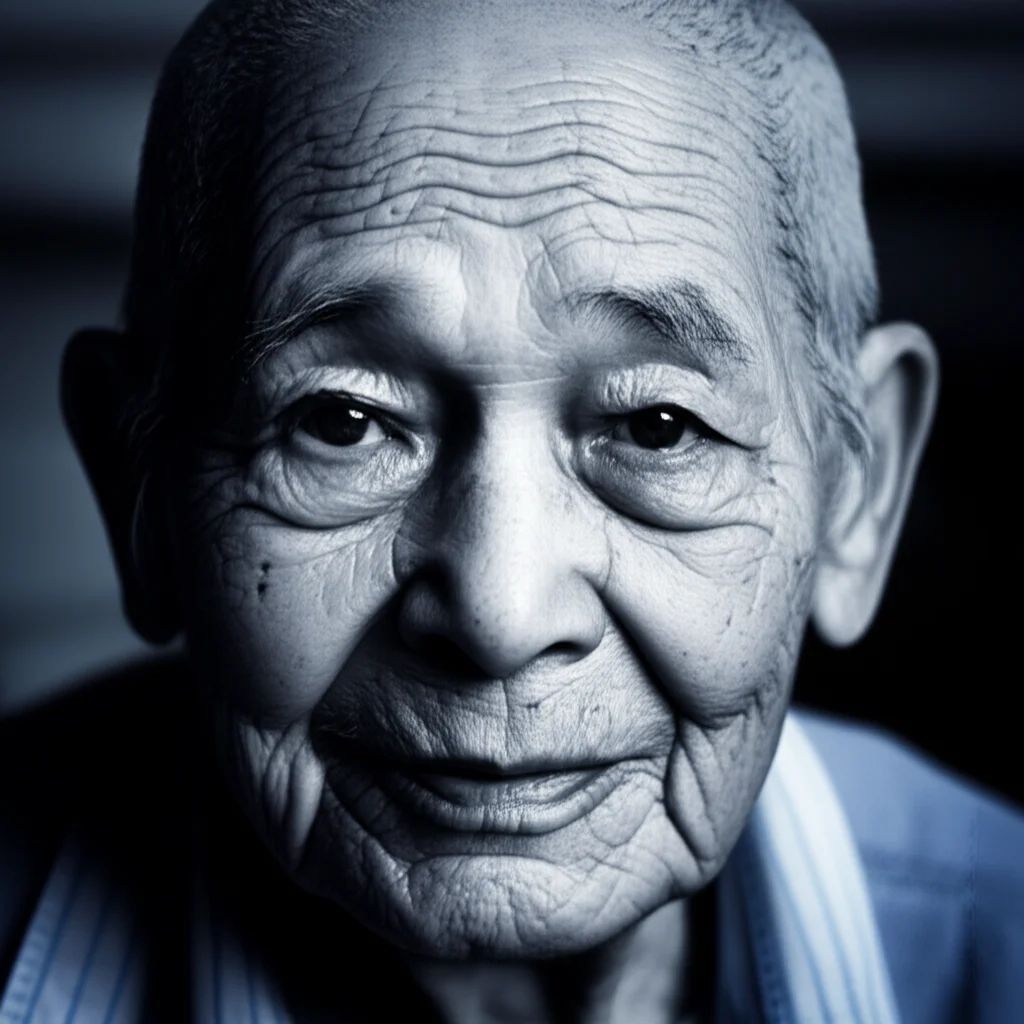

China’s Oldest-Old: When Care Needs Go Unmet, What Happens to Quality of Life?

Alright, let’s talk about something that’s becoming a massive deal worldwide, but especially in places like China: how we look after our oldest folks. I mean, hitting 80, 90, or even 100 is an incredible milestone, but let’s be real, it often comes with needing a bit more help with daily life. And when that help isn’t there? Well, that’s what I want to dive into today, specifically looking at what happens with unmet long-term care (LTC) needs and how it messes with the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) for the oldest-old in China.

I stumbled upon this really insightful study, and it got me thinking. We’re seeing more people live longer than ever – which is fantastic! China, for instance, had about 35.8 million people aged 80 and over, including around 110,000 centenarians, back in 2020. That’s nearly a quarter of the world’s oldest-old population! But living a long life and living a good long life are two different things, aren’t they?

So, What Are We Talking About with “Unmet LTC Needs”?

Basically, unmet LTC needs happen when someone needs assistance – whether it’s from another person or a device – for their daily activities, but they just don’t get it, or what they get isn’t enough. Think about things like getting dressed, making meals, or even just moving around. The study I’m looking at focused on perceived unmet needs. This is super important because it’s about how the individuals themselves feel about the care they’re getting (or not getting). They’re the best judges, right? If they feel their needs aren’t met, that’s a big indicator of a gap in the system.

There are different ways to look at this. Some studies focus on specific symptoms or difficulties with Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) like bathing or eating, or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs) like managing money or using the phone. This study, however, zeroed in on the general feeling of “I need help, but I’m not getting it.” This subjective experience can really predict health outcomes and quality of life because it taps into satisfaction and whether folks feel supported, especially emotionally and psychologically.

Why China’s Oldest-Old, and Why Hainan?

This research, called the China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study (CHCCS), is pretty unique. It didn’t just look at a general older population; it specifically targeted those aged 80-99 and all centenarians in Hainan province. Hainan, by the way, is China’s southernmost province and boasts the highest percentage of centenarians in the country! So, it’s a pretty special group to learn from.

The researchers gathered a ton of info through face-to-face interviews, exams, and lab analyses. They looked at everything from demographics to health status, and crucially, their LTC needs and what kind of support they were receiving.

To figure out who needed LTC, they used standard assessments for IADLs (like using a phone, laundry, cooking, shopping) and ADLs (grooming, bathing, dressing, mobility). If someone said they needed help with any of these, they were considered to have an LTC need. Then, the big question: “Do you require assistance for daily activities of daily living?” If they said, “I need assistance, but no one provided it,” bingo – that’s an unmet need.

Measuring What Makes Life Good: HRQOL

To get a handle on health-related quality of life, the study used something called the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire. It’s a standard tool that asks people about their current health across five areas:

- Mobility

- Self-care

- Usual activities

- Pain/discomfort

- Anxiety/depression

Each area has three levels: no problems, moderate problems, or severe problems. From this, they calculate a QALY (Quality-Adjusted Life Year) score, which ranges from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). It’s a neat way to quantify overall well-being.

The study included 1,444 folks, with an average age of a whopping 95.75 years! Most were women (about 76%), lived in rural areas (over 80%), and a large majority (nearly 88%) were illiterate. Most were widowed. These details paint a picture of the population we’re talking about.

The Sobering Numbers: How Many Have Unmet Needs?

Okay, here’s the kicker: 32.69% of these oldest-old individuals reported unmet LTC needs. That’s nearly one in three. To put that in perspective, this figure is generally higher than what you see in many high-income countries, where it can range from 1% to 26%. It’s also higher than an average of 25.1% reported in a systematic review of older people globally. This isn’t entirely surprising, as in China, LTC has traditionally been a family responsibility rather than a government one. In this study’s sample, almost everyone (99.38%) relied on informal care from family.

Who’s Falling Through the Cracks?

The study found some clear patterns. Unmet needs were more common among:

- Those over 105 years old (over 50% of them!) compared to the “younger” 80-85 group (around 16%).

- People who were illiterate.

- Rural residents.

- Those living alone.

- Individuals with more severe ADL or IADL disabilities.

- Those with vision and hearing impairments.

Essentially, economic and social deprivation played a big role. If you have a lower socioeconomic status, you might live in a smaller household, be single or widowed, and just have less access to informal care. The rural-to-urban migration in China also means adult children might be far away from their elderly parents in rural areas, making it harder to provide care.

The Ripple Effect: Unmet Needs and Quality of Life

This is where it really hits home. The research clearly showed that individuals with unmet LTC needs reported lower QALY scores (β=-0.04, p<0.01). Their overall quality of life was worse. It makes sense, doesn't it? If you're struggling daily without the help you need, life just isn't going to feel as good.

But it wasn’t just a general dip. When they looked at the five dimensions of the EQ-5D, they found that unmet LTC needs were significantly linked to worse outcomes in:

- Mobility (β = 0.18, p<0.05)

- Self-care (β = 0.19, p<0.05)

- Pain or discomfort (β = 0.27, p<0.01)

- Anxiety or depression (β = 0.09, p<0.01)

A positive sign on these coefficients means a negative relationship – more unmet needs meant more severe problems in these areas. So, people were struggling more to get around, take care of themselves, were in more pain, and felt more anxious or depressed. This lines up with other studies showing unmet healthcare needs often go hand-in-hand with depression.

The Family Factor and Sustainability

In China, as this study confirms, family – usually children or spouses – are the main providers of long-term care. Very few use institutional care or paid formal care. This is partly cultural; there’s a strong tradition of filial piety where children are expected to care for aging parents. Plus, formal home care and nursing homes are still developing in China and aren’t always available or affordable.

While the study found that living with children or grandchildren (without a formal carer) meant people were less likely to report unmet LTC needs, this informal care model is under immense pressure. Think about it:

- Caregiver burden: Informal care can take a huge toll on the caregiver’s health, finances, and ability to work.

- The one-child policy legacy: Many families now have a “4-2-1” structure, where two adults (a couple) might eventually need to care for four aging parents and one child. That’s a monumental task.

- Longer lifespans: People are living longer, often with chronic conditions, meaning the period of needing care is also extending.

This kinship-based system, while deeply ingrained, just isn’t sustainable in the long run as the population ages so rapidly. China faces a huge challenge in building a more formal, sustainable LTC system.

A Few Caveats and Where We Go From Here

Like any study, this one has its limitations. The data came only from Hainan Province, so we can’t say for sure it’s the same story across all of China. Also, because it was a snapshot in time (cross-sectional), it’s hard to definitively say unmet needs cause lower quality of life, though the link is pretty strong. Future research could follow people over time and look at more diverse regions.

The way they measured unmet needs was also quite general (“Do you require assistance… and not get it?”). Future studies could dig deeper into specific types of unmet needs – emotional, social, physical support, etc.

The Big Takeaway

So, what’s the upshot of all this? Well, it’s pretty clear that a significant chunk of China’s oldest-old population, especially those who are rural and economically vulnerable, are struggling with unmet long-term care needs. And this isn’t just an inconvenience; it seriously impacts their health and overall quality of life, affecting their mobility, ability to care for themselves, pain levels, and mental well-being.

These findings really shout out the need for better strategies and policies. We’re talking about targeted interventions to make sure these vulnerable folks get the support they need. It’s not just about adding years to life, but life to years, right? And for other countries with rapidly aging populations, especially lower and middle-income ones, there are definitely lessons to be learned here. Addressing these unmet needs is crucial for helping our elders age with dignity and well-being.

It really makes you think about how we, as a society, value and care for those who’ve lived the longest among us. Food for thought, indeed.

Source: Springer