TRPV3’s Wild Side: Unveiling the Super-Permeable Pentamer

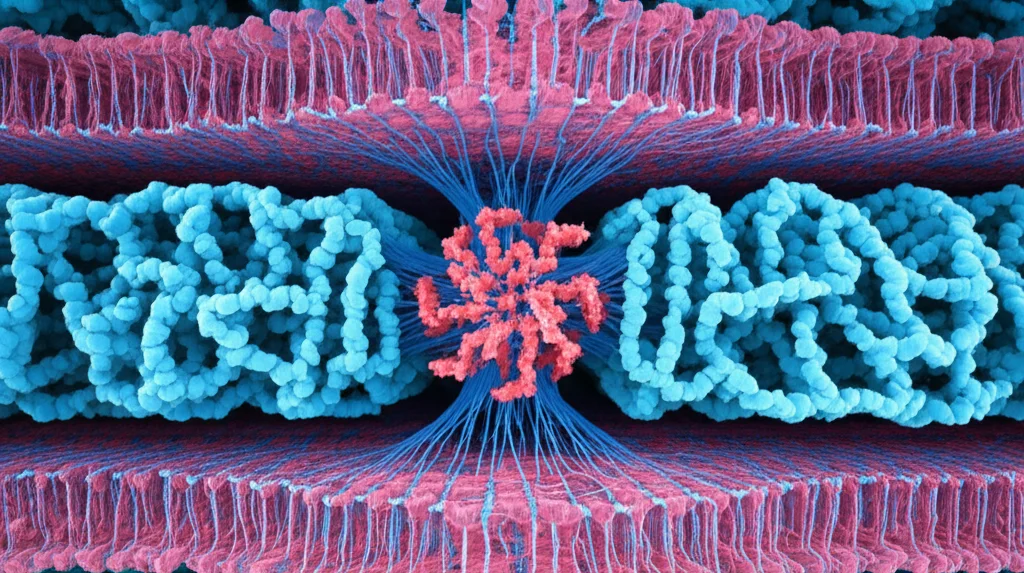

Hey there! Let’s dive into the fascinating world of tiny gates inside our bodies, specifically one called TRPV3. You know, these things are usually like little bouncers, controlling what gets in and out of our cells. For the longest time, we thought TRPV3 always showed up as a group of four, a ‘tetramer’. It’s the standard setup for its whole family, the TRP channels, which are super important for sensing things like temperature, touch, and even certain chemicals.

But science is always full of surprises, isn’t it? Turns out, TRPV3 has a secret identity! We recently stumbled upon a rare, fleeting moment where it forms a group of five – a ‘pentamer’. Imagine discovering your favorite band sometimes plays a gig with a surprise fifth member! This pentamer state isn’t the usual gig; it’s transient, meaning it pops in and out of existence, hanging out in equilibrium with its more common tetrameric form.

Unveiling the Pentamer Puzzle

Finding this pentamer was pretty cool, thanks to some high-tech tools like high-speed atomic force microscopy (HS-AFM). This allowed us to actually *see* these molecular machines moving around in real-time. We even got a blurry first picture using cryo-EM, which hinted that this pentamer had a much bigger hole in the middle than the tetramer. But honestly, that first look was like trying to understand a complex painting with fuzzy glasses on. A lot of the details were just… missing.

A Sharper Look: The New Structure

So, we rolled up our sleeves and went back to the cryo-EM. And wow, did we get a better picture! This new, higher-resolution structure of the TRPV3 pentamer is a game-changer. It showed us something called a ‘domain-swapped architecture’, which is how the different parts of each subunit link up with their neighbors. It also revealed that the spot where certain molecules (like vanilloids) usually bind in the tetramer is all squished up, or ‘collapsed’, in the pentamer. And the pore? Yep, confirmed – it’s *large*.

Getting this clearer view wasn’t easy. It involved some serious data crunching and using machine learning to find those tricky side views that were hiding from us before. But the effort paid off, giving us a much more complete model, even showing us parts we couldn’t see before, like the crucial S4–S5 linker region. This linker confirmed the domain-swapped setup, just like its tetramer cousin.

The Big Pore Story: Permeability Secrets

Now, about that big pore. Comparing the pentamer’s pore to the tetramer’s (both closed and open states) is like comparing a garden gate to a double doorway. The pentamer’s pore is significantly wider, especially at key choke points like the selectivity filter (SF) and the gate. We’re talking diameters that are multiple times larger than in the tetramer!

This massive pore size immediately made us think: could this be the mysterious ‘pore-dilated’ state that other studies have hinted at? This phenomenon is seen in electrophysiology experiments where, under certain conditions, TRP channels start letting through really *large* molecules, like NMDG+, Tris+, and 2-MAE+, which are way too big for the normal pore. Our structural analysis suggested the pentamer’s pore is definitely big enough to let these bulky cations through without a squeeze.

To really test this, we used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and potential of mean force (PMF) calculations. Think of this as running tiny, super-detailed computer experiments, watching molecules move through the channel. These simulations showed that the energy barriers for these large cations to pass through the pentamer’s pore are surprisingly low – comparable to how easily sodium ions (the small ones) go through the *open* tetramer. So, yes, the pentamer seems to be a super-permissive channel, happy to let the big guys through.

What Holds It Together (or Doesn’t)?

We also dug into how the individual subunits in the pentamer stick to each other compared to the tetramer. It’s all about the ‘subunit interfaces’ – where the building blocks connect. In the standard closed tetramer, there are lots of interactions holding everything tightly, including some special ones helped by a lipid molecule (the vanilloid lipid) that acts like molecular glue in the vanilloid binding site.

In the pentamer, however, many of these interactions, especially in the transmembrane domain (TMD), are significantly reduced. The vanilloid binding site is collapsed, and that lipid glue is gone! This makes the pentamer’s interfaces seem weaker. Interestingly, the open and inactivated tetramer states also have fewer interactions than the closed state, but the pentamer seems to have the fewest interactions *per interface*.

Our MD simulations backed this up, showing the pentamer is generally more flexible, especially in its intracellular parts. Even though the interfaces are weaker, the pentamer has *five* interfaces compared to the tetramer’s four. So, when you add up all the interactions, the pentamer’s total interaction energy is actually comparable to the closed tetramer, and potentially more stable than the open or inactivated tetramer states. It’s a bit counterintuitive – weaker connections individually, but more connections overall!

Agonists: The Destabilizers

So, if the pentamer is a bit fragile at its connections, how does it form? We suspected that things that activate TRPV3 might play a role. We used nano differential scanning fluorimetry (nano-DSF), a technique that measures how stable a protein is when you heat it up. We tested several known TRPV3 activators like 2-APB, camphor, and even the general anesthetic propofol, alongside the reported pore-dilation agent DPBA.

And guess what? At concentrations known to activate the channel or cause pore dilation, these compounds significantly *destabilized* TRPV3! They lowered the temperature at which the protein starts to unfold. Control substances that don’t activate TRPV3 didn’t have this effect. This suggests that activation, especially strong activation, makes the TRPV3 tetramer less stable.

How Does It Happen? The Proposed Mechanism

Putting all this together – the HS-AFM showing subunits swapping, the structure revealing weak interfaces, the MD showing dynamics, and the nano-DSF showing destabilization by activators – we can propose a story for how the tetramer turns into a pentamer.

It seems that activators first nudge the stable, closed tetramer into its open state. This displaces that vanilloid lipid glue and weakens the subunit interfaces, making the tetramer less stable. The open state quickly transitions to an inactivated state, which is a bit more stable than the open state but still has weaker interfaces than the closed tetramer. This inactivated state is key. We think the transition to the pentamer happens from this state because its interfaces are already weakened, especially where the fifth subunit needs to slide in.

Our hypothesis is that a subunit interface in the inactivated tetramer partially breaks open, allowing a free TRPV3 subunit floating nearby in the membrane to insert itself into the gap. This requires overcoming an energy barrier, but by going through the less stable open and inactivated states first, the channel breaks down that big barrier into smaller, more manageable steps. It’s like dismantling a wall brick by brick instead of trying to knock the whole thing down at once.

The fact that activators make the protein less stable and increase the population of pentamers seen by HS-AFM strongly supports this idea. The pentamer, despite its individually weaker interfaces, gains stability overall by incorporating that fifth subunit and forming five interfaces.

So, there you have it! We’ve gotten a much clearer picture of the elusive TRPV3 pentamer. It’s a dynamic, hyper-activated state with a surprisingly large pore that can let through molecules the tetramer can’t. And it seems that pushing the channel hard with activators can nudge it towards this unusual, super-permeable form by making its usual tetrameric structure less stable. It’s a fascinating new layer to the story of how these important channels work, and it opens up all sorts of questions for future research!

Source: Springer