Tiny RNA Hero? Unraveling a New Pathway in the Fight Against Alzheimer’s

Alright, let’s talk about something that affects so many lives, something really tough: Alzheimer’s disease. You know the picture – memory fading, confusion setting in, a slow, heartbreaking decline. From a scientific point of view, it’s this incredibly complex neurodegenerative mess, characterized by sticky plaques of β-amyloid (Aβ), tangled tau proteins inside neurons, and, sadly, the loss of those precious brain cells. It’s a huge puzzle, and finding ways to tackle it feels like searching for a needle in a haystack.

The Alzheimer’s Challenge

For ages, we’ve known about the hallmarks: those amyloid plaques building up outside neurons and neurofibrillary tangles forming inside. But it’s not just about the gunk. The brain’s own cleanup crew, cells called microglia, get involved. Early on, they try to clear the Aβ, which is great. But as AD progresses, they can get stuck in a ‘bad’ state, called M1-type polarization. When that happens, they start pumping out inflammatory factors and toxic stuff that just makes everything worse for the surrounding neurons.

Then there’s tau. Normally, it’s like the scaffolding for the neuron’s internal transport system. But in AD, it gets over-phosphorylated – basically, too many phosphate groups get stuck on it. This makes it detach from the scaffolding, causing the structure to collapse, and the tau proteins clump together into those nasty tangles. This totally messes up neuronal function and eventually leads to cell death. It’s a double whammy: external plaques and internal tangles, all contributing to the brain’s decline.

Tiny Messengers and Cellular Antennas

Now, science is always looking in new places for answers. Lately, these little molecules called transfer RNA (tRNA)-derived small RNAs, or tsRNAs for short, have popped up on the radar. They’re basically small pieces broken off from the tRNAs we all have, and it turns out they’re doing a lot more than just helping build proteins. They seem to be important regulators in all sorts of biological processes. But their specific role in AD? That’s been a bit of a mystery.

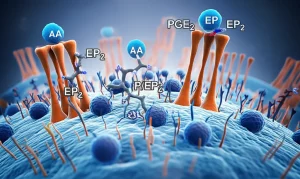

At the same time, another family of proteins called Eph receptors has caught our eye. Think of them as cellular antennas that receive signals from other cells. They’re super important for things like how cells move around, how the brain develops, and even how blood vessels form. They have partners, called ephrins, and when an Eph receptor meets its ephrin partner, they send signals back and forth. We already knew some Eph receptors, like EphA4 and EphB2, are linked to problems with synapses (the connections between neurons) in AD. But how do tsRNAs fit into this picture, and could they be talking to Eph receptors in AD? That’s what we really wanted to find out.

Our Deep Dive into the Brain’s Signals

So, we set up an investigation. We used a common model for AD research – mice that are genetically engineered to develop some key AD features, specifically those Aβ plaques (they’re called APP/PS1 transgenic mice). We looked at their brain tissue, specifically the cortex, and used some pretty advanced technology called RNA sequencing to see which tsRNAs were present and how their levels differed compared to healthy mice.

Once we had a list of tsRNAs that looked interesting (meaning their levels were significantly different in the AD mice), we used bioinformatics tools – basically, powerful computer analysis – to predict which genes these tsRNAs might be targeting. See, tsRNAs can act a bit like another type of small RNA called miRNAs, binding to messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and stopping them from being translated into proteins. We were particularly interested if any of these tsRNAs were targeting genes in the Eph receptor family.

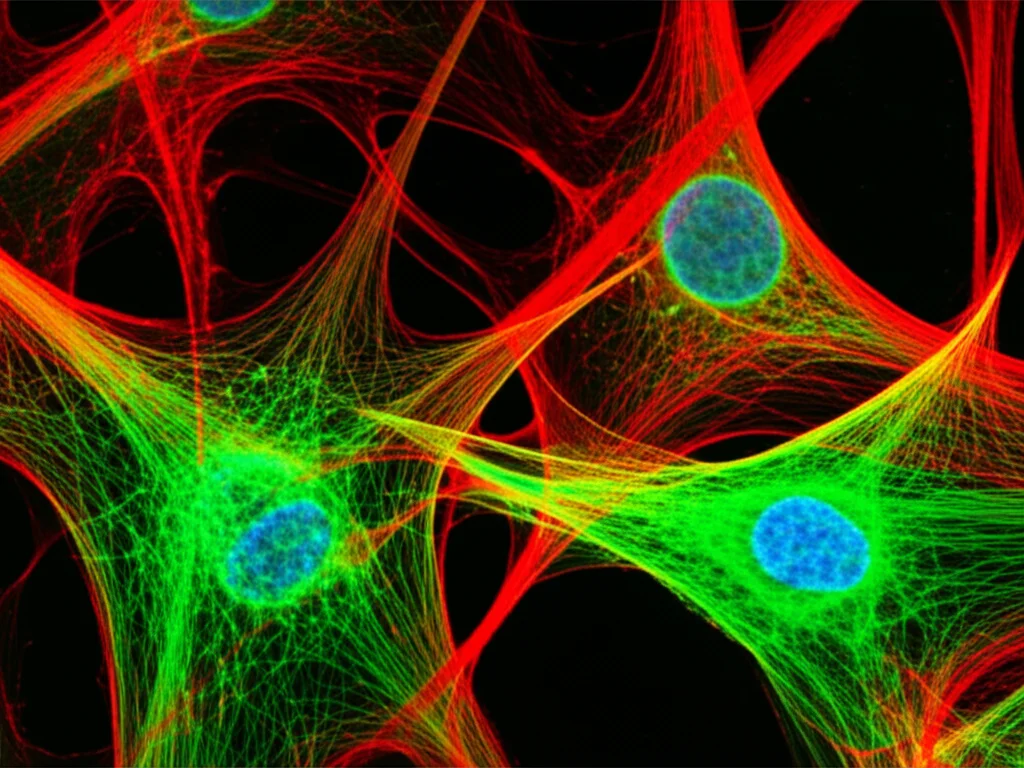

We didn’t stop there. We also worked with cell cultures in the lab – specifically, BV-2 cells, which are a type of mouse microglial cell, and HT22 cells, which are mouse hippocampal neurons. We treated these cells with Aβ to mimic what happens in AD and watched how the levels of our interesting tsRNAs and potential target genes changed. We even did experiments where we artificially increased the levels of a specific tsRNA (using something called a ‘mimic’) or blocked a target gene (using ‘siRNA’) to see what effect it had on the cells and the signaling pathways inside them. To confirm that a specific tsRNA was *really* binding to a target gene, we used a clever test called a dual-luciferase reporter assay. And to see the proteins and their locations, we used Western blotting and immunofluorescence, which are like molecular and cellular photography.

The Crucial Connection Emerges

Okay, so what did we find? Well, it turns out our deep dive paid off! We identified a specific tsRNA, one derived from the 5′ end of a tRNA, called tRFAla-AGC-3-M8. And guess what? In the AD mice, the levels of tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 were significantly *down*. This was a big clue.

Then, we looked at the Eph receptors. Our bioinformatics analysis pointed to one in particular: EphA7. And wouldn’t you know it, in the AD mice, the levels of EphA7 were significantly *up*. This inverse relationship between tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 being low and EphA7 being high was super interesting.

Using that dual-luciferase assay I mentioned, we got solid evidence that tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 actually binds directly to the mRNA of EphA7. This binding seems to work like a switch, turning down the production of the EphA7 protein. So, when tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 levels drop in AD, it’s like the switch is broken, and EphA7 production goes unchecked, leading to higher levels of the EphA7 protein.

We also saw where this high EphA7 was showing up in the AD mouse brains. It was particularly noticeable in the hippocampus, a brain region critical for memory that’s hit hard by AD. Interestingly, we saw high EphA7 not just in neurons but also in those aggregated microglia we talked about earlier. This was the first time anyone had really highlighted EphA7 expression in aggregated microglia in AD, which is pretty neat.

Unraveling the Signaling Chain

So, we have low tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 leading to high EphA7. But what does high EphA7 *do* in the context of AD? This is where the signaling pathways come in. We investigated which pathways might be activated when EphA7 levels are high.

We found that in the AD mice, two key proteins in a specific signaling pathway – ERK1/2 and p70S6K – were significantly more phosphorylated. Phosphorylation is often like an “on” switch for proteins, so this meant this pathway was more active. We saw the same thing happen in our BV-2 and HT22 cells when we treated them with Aβ – the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p70S6K went up.

This is where things get really interesting. When we artificially increased tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 levels in the Aβ-treated cells (using the mimic), it brought down the high EphA7 levels. And crucially, it also significantly reduced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p70S6K. It was like adding the missing tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 put the brakes back on this pathway.

To be absolutely sure that tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 was doing this *through* EphA7, we did another experiment. We used siRNA to specifically knock down (reduce the expression of) EphA7 in the Aβ-treated cells. And guess what? Reducing EphA7 directly also significantly reduced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p70S6K, just like increasing tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 did. This strongly suggests that tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 controls this pathway by regulating EphA7.

The Downstream Effects: Inflammation and Damage

Okay, so we’ve got the chain: low tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 -> high EphA7 -> activated ERK1/2-p70S6K pathway. But what are the consequences of this activated pathway in AD?

Remember those microglia getting stuck in the M1 inflammatory state? We looked at a marker for that state, a protein called iNOS. In our BV-2 microglial cells treated with Aβ, iNOS levels went up, and the cells started looking more like those activated, star-shaped M1 microglia. But when we increased tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 or knocked down EphA7, the iNOS levels dropped, and the microglia looked more normal. This tells us that the tRFAla-AGC-3-M8/EphA7/ERK1/2-p70S6K pathway is involved in driving microglial inflammation in AD.

What about the neurons? Remember tau hyperphosphorylation leading to tangles and damage? We looked at phosphorylated tau (p-tau) levels in our HT22 neuronal cells treated with Aβ. As expected, p-tau levels went up, and the neurons showed signs of damage, like shrinking cell bodies. But when we increased tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 or knocked down EphA7 in these neurons, the p-tau levels went down, and the neurons looked healthier, extending their processes more normally. This shows that this same pathway is also contributing to tau problems and neuronal damage.

So, it all ties together: Aβ stress reduces tRFAla-AGC-3-M8, which lets EphA7 levels rise. High EphA7 activates the ERK1/2-p70S6K pathway. This activated pathway then fuels microglial inflammation and causes tau hyperphosphorylation and damage in neurons. It’s a clear chain of events linking this tiny RNA to the big problems seen in AD.

A Glimmer of Hope for Therapy

This is really exciting because it gives us a much clearer picture of a specific mechanism driving AD pathology. For the first time, we’ve identified tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 as a key player, showing how its reduction under Aβ stress contributes to the disease via the EphA7-ERK1/2-p70S6K pathway.

Why is this important? Well, understanding the *specific* steps involved in the disease process is crucial for developing effective treatments. This pathway, the EphA7-ERK1/2-p70S6K axis, now looks like a really promising target. If we can find ways to:

- Boost the levels of tRFAla-AGC-3-M8, or

- Block the activity of EphA7, or

- Inhibit the ERK1/2-p70S6K pathway

…we might be able to slow down or even prevent the neuroinflammation and neuronal damage that are so devastating in AD.

Think about it – tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 itself could potentially be used as a therapeutic agent, or maybe we could develop drugs that mimic its action or block its target, EphA7. This study provides strong evidence that targeting this specific pathway could be a valid strategy.

Furthermore, because tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 levels are reduced in AD and correlate with the disease state, it might also serve as a potential biomarker – something we could measure (maybe in bodily fluids, though our study focused on brain tissue and cells) to help diagnose AD earlier or track its progression.

What We Still Need to Explore

Of course, science is a journey, and there are always more questions. Our study gives us this fantastic new insight, but it also opens doors for further research. For example, we saw that the changes in tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 expression might be dynamic, especially in microglia as they change states. We need to understand better *why* tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 levels drop under Aβ stress. Is it actively degraded? Is its production shut down?

Also, given that tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 is found in both neurons and microglia, it’s possible it plays a role in how these cells communicate with each other in the brain, particularly in vulnerable areas like the hippocampus. Exploring this neuron-microglia crosstalk mediated by tsRNAs could reveal even more about AD pathology.

Wrapping Up

But even with those questions remaining, this study is a significant step forward. It clearly demonstrates that tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 plays a specific, crucial role in AD pathology by regulating EphA7 and the subsequent ERK1/2-p70S6K signaling, which drives inflammation and neuronal damage. It’s a complex picture, but finding these specific molecular pathways gives us real, tangible targets to pursue in the ongoing fight against this challenging disease. It’s exciting to think about the potential for new diagnostic tools and, hopefully, effective therapies emerging from this kind of foundational research.

Source: Springer