Unraveling the Web: How Childhood Trauma Shapes Psychosis Pathways

Hey there! Let’s dive into something pretty fascinating and, frankly, a bit heavy, but super important for understanding how our early experiences can ripple through our lives. We’re talking about childhood trauma and how it might connect to something as complex as new-onset psychosis.

You know, for a while now, we’ve understood that going through tough stuff as a kid – things like abuse or neglect – can increase the chances of developing psychosis later on. And if someone *does* develop a psychotic disorder, those early traumas often make things harder, impacting their symptoms and how well they manage in daily life.

We’ve seen studies showing that trauma can really mess with functioning – like holding down a job, having relationships, or just generally getting by. Some research even hinted that neglect might be particularly tough on functioning compared to abuse, and that our social lives seem to take a big hit.

But here’s the thing: while we knew there was a link, the *how* was still a bit murky. How do specific types of trauma connect to specific symptoms, and how do *those* then influence different areas of functioning? It’s like trying to trace threads in a giant, tangled ball of yarn. We needed a better way to see the whole picture, all at once.

Enter Network Analysis: A New Way to See the Connections

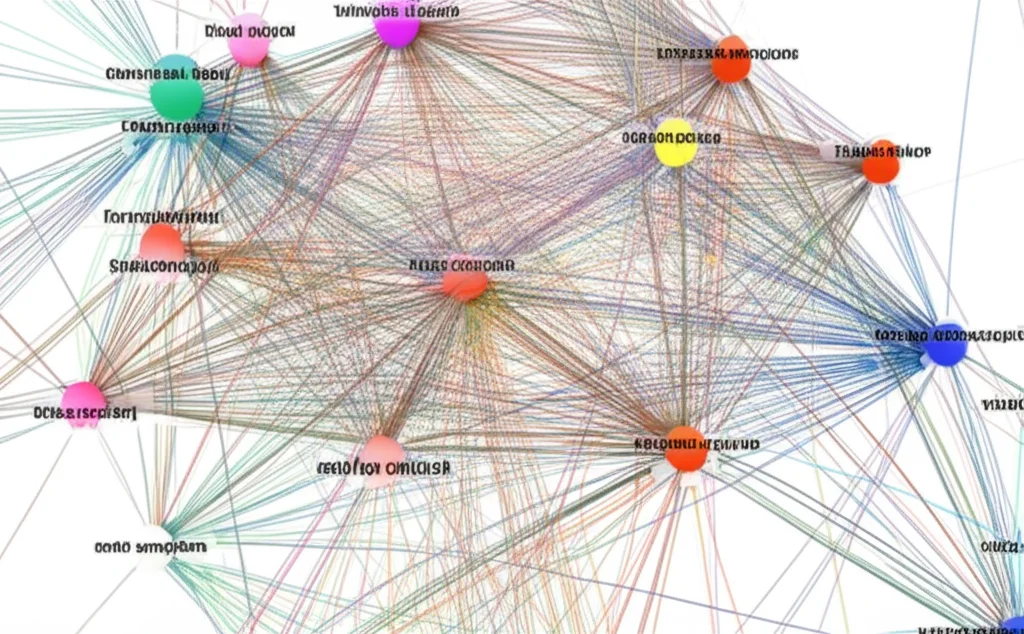

This is where a really cool approach called network analysis comes in. Think of it like mapping out a city. Instead of just saying “there are roads and buildings,” you map *every* street, *every* intersection, and see how traffic flows. In this context, the “buildings” and “intersections” are things like different types of trauma, specific symptoms, and various aspects of functioning. The “roads” are the connections between them.

This method lets us look at all these factors simultaneously and see which ones are most connected, which ones act as “bridges” between different groups, and what the most direct “pathways” are through the network. It doesn’t tell us definitively that A *causes* B, but it shows us the strongest, most likely routes of influence *within* the system at a given time. Pretty neat, right?

Previous studies using network analysis had looked at trauma and symptoms, or symptoms and functioning, but rarely all three together in people just starting to experience psychosis. And often, they used broad scores for trauma or functioning, which is like looking at the city from a plane – you see the major highways, but you miss the smaller, crucial side streets.

What This Study Did

So, a group of researchers decided to use this network approach to get a more detailed view. They looked at data from 277 patients in Switzerland who were in an early intervention program for new-onset psychosis. These were people relatively early in their journey, which is a key time to understand what’s going on before things get too complicated by long-term illness or treatment.

They gathered detailed information on:

- Five common types of childhood trauma (before age 16): sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect.

- Clinical symptoms: using a standard scale called the PANSS, which covers positive symptoms (like hallucinations, delusions), negative symptoms (like lack of motivation, social withdrawal), and general psychopathology (like depression, anxiety, tension).

- Functioning: using an adapted scale that looked at different areas like work status, global functioning, socio-personal functioning, interest in life, and energy level. (Interestingly, they also looked at ‘independence,’ but more on that in a bit).

They then built a network model with all these pieces to see how they connected.

The Big Findings: Two Distinct Pathways Emerge

What they found was super insightful! The network showed that trauma types, symptoms, and functioning domains tended to hang out in their own clusters, but there were definite links connecting them. And when they mapped the *shortest, most efficient* pathways from childhood trauma to functioning, two main routes popped out:

- The first pathway linked all the different types of childhood trauma, but particularly highlighted sexual abuse, and then went through depression symptoms, leading primarily to issues with occupational functioning (like work status).

- The second major pathway linked most types of trauma, with a strong emphasis on physical neglect, and then went through stereotyped thinking (a symptom related to disorganization/negative symptoms), leading mostly to difficulties in socio-personal functioning, as well as impacting global functioning, interest, and energy.

Think of it like this: it’s not just *any* trauma leading to *any* problem. It seems specific types of trauma might be more strongly associated with certain symptom patterns, which in turn impact particular areas of life functioning.

They also noticed that having *multiple* types of trauma seemed to create more or shorter pathways to functioning issues, suggesting a cumulative effect – the more types of trauma, the stronger the connection to later difficulties.

An interesting side note: the ‘independence’ aspect of functioning seemed pretty isolated in the network, meaning it wasn’t strongly connected to the trauma or symptom nodes in this study. This actually lines up with some other research suggesting trauma might not directly impact independent living status as much as other functional areas in people with psychosis.

What Does This All Mean? The “Ecophenotype” Idea

These findings really support an idea that’s been gaining traction: that there might be different “pathways” to psychosis, potentially linked to different underlying vulnerabilities or experiences. The researchers here suggest their findings align with the concept of two distinct “ecophenotypes” (basically, different ways the environment shapes the illness):

- An affective ecophenotype: strongly linked to sexual abuse, going through symptoms like depression, and primarily impacting work/occupational functioning. This fits with ideas about trauma affecting stress sensitivity and emotional regulation.

- A cognitive ecophenotype: strongly linked to physical neglect, going through symptoms like stereotyped thinking (related to disorganization/negative symptoms), and primarily impacting social/personal functioning, interest, and energy. This aligns with ideas about neglect affecting cognitive development and leading to more chronic, deficit-like forms of the illness.

It’s like different early experiences set you on different paths, influencing the *type* of symptoms you might experience and the *specific* areas of your life that are most affected.

So, What’s the Takeaway for Real Life?

This isn’t just academic stuff; it has real implications for how we approach care:

- Spotting Vulnerability: It highlights the importance of asking about and understanding a person’s childhood trauma history, and maybe even paying extra attention to those who’ve experienced multiple types of trauma.

- Targeting Treatment: It reinforces that treating psychosis isn’t just about tackling hallucinations or delusions. Symptoms like depression, which are often present and can be undertreated in psychosis, are crucial targets, especially given their role in the sexual abuse/occupational pathway.

- Personalized Care: If these distinct pathways hold up, it suggests we might need more tailored treatments. Someone whose difficulties align more with the “cognitive” pathway might benefit more from therapies focused on cognitive skills or social interaction, while someone on the “affective” path might need more support with emotional regulation and stress management.

- Focusing on Functioning: The study also shows that difficulties in one area of functioning (like social interaction) can be tightly linked to others (like interest and energy), and these can maintain problems even if symptoms improve. This really underlines the need for comprehensive rehabilitation that targets multiple aspects of daily life.

A Note on Limitations (Because Science Isn’t Perfect)

Like any study, this one has its limits. They used a custom questionnaire for trauma, not a widely standardized one, which can make comparisons tricky. Also, it’s a snapshot in time (cross-sectional), so while network analysis suggests pathways, it can’t definitively prove cause and effect. We can’t say for sure that trauma *caused* these symptoms and functioning issues based *only* on this study, though the findings align with existing theories. They also couldn’t include every possible factor that influences psychosis, like genetics, age of trauma, or other psychological factors.

Looking Ahead

This study is a fantastic step, using a powerful tool to shed new light on a complex issue. But it’s just one piece of the puzzle. Future research needs to follow people over time (longitudinal studies) to see how these connections develop and change, use standardized trauma measures, and try to include even more factors to build an even more complete picture.

Wrapping It Up

Ultimately, this research gives us a much clearer view of the intricate dance between childhood trauma, clinical symptoms, and functional outcomes in the early stages of psychosis. By identifying these distinct pathways – perhaps an affective one linked to sexual abuse and occupational issues, and a cognitive one linked to physical neglect and socio-personal challenges – it moves us closer to the exciting possibility of truly personalized care for people experiencing psychosis. It reminds us that understanding someone’s past isn’t just about history; it’s key to shaping a better future.

Source: Springer