Prostatectomy’s Secret: Tracking Tumor Cells in the Local Bloodstream

Hey there! Let’s chat about something pretty interesting in the world of prostate cancer research. You know how prostate cancer is super common for guys? And how sometimes, even after surgery, it can come back or spread? Well, scientists are always trying to figure out *how* and *why* that happens. One big piece of the puzzle is understanding how tumor cells might escape the original tumor and travel through the body.

We’ve heard a bit about these escapees, called circulating tumor cells (CTCs), showing up in the peripheral blood – that’s the blood just chilling in your arms and legs. Finding CTCs there can sometimes be a sign that things are getting a bit more serious. But here’s a thought: what happens right at the source during surgery? Does the very act of removing the prostate stir things up and release cells locally?

That’s the million-dollar question this study tackled, and honestly, it’s been a bit of an under-investigated area. Most research looks at CTCs far away from the tumor site. But what about the blood vessels right *around* the prostate, specifically the prostatic plexus? That’s like the local highway system for blood draining from the area.

Peeking into the Prostatic Plexus

So, what did these clever researchers do? They rounded up 103 guys who were getting their prostate removed because of early-stage cancer. These fellas hadn’t had any treatment yet, which is key. During the surgery, they did something pretty unique: they collected blood samples from two places at the same time:

- Blood right from the prostatic venous plexus (the local spot).

- Blood from a peripheral vein (like your arm, the systemic spot).

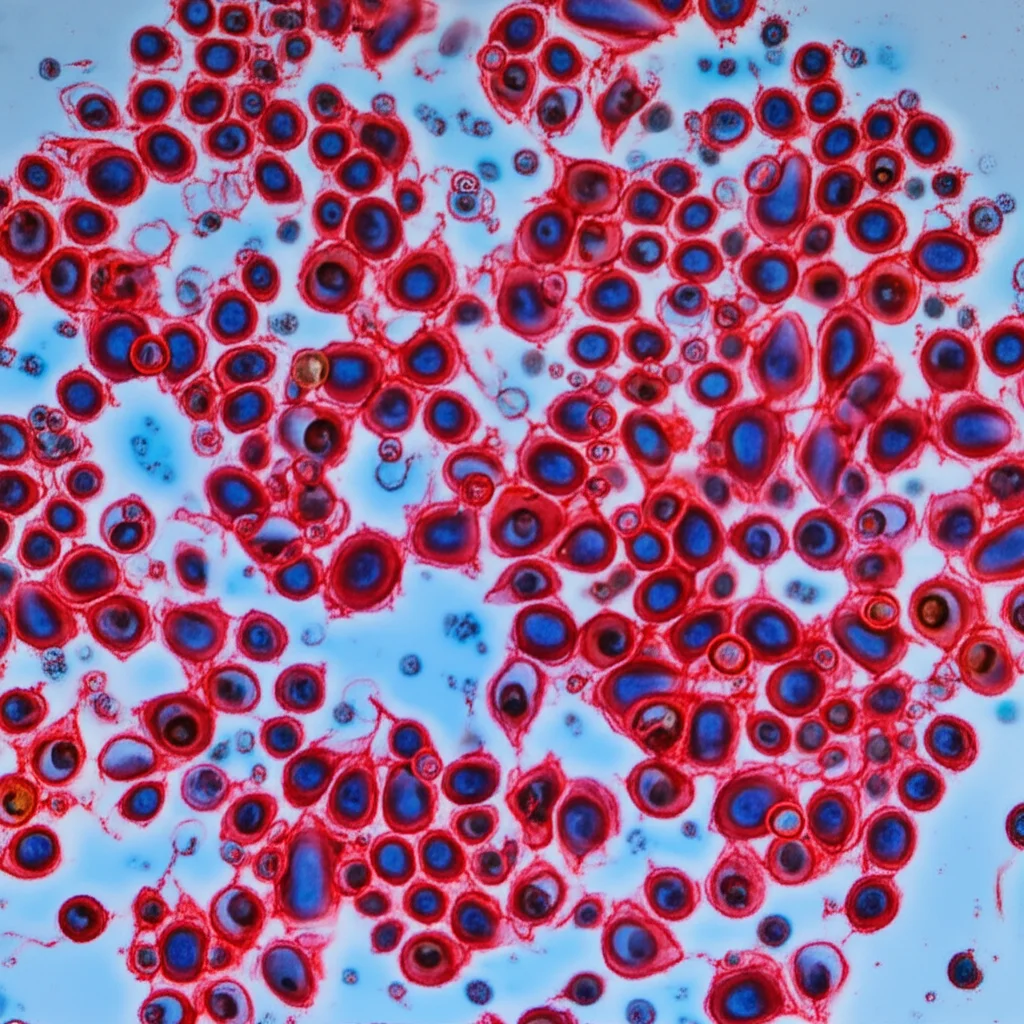

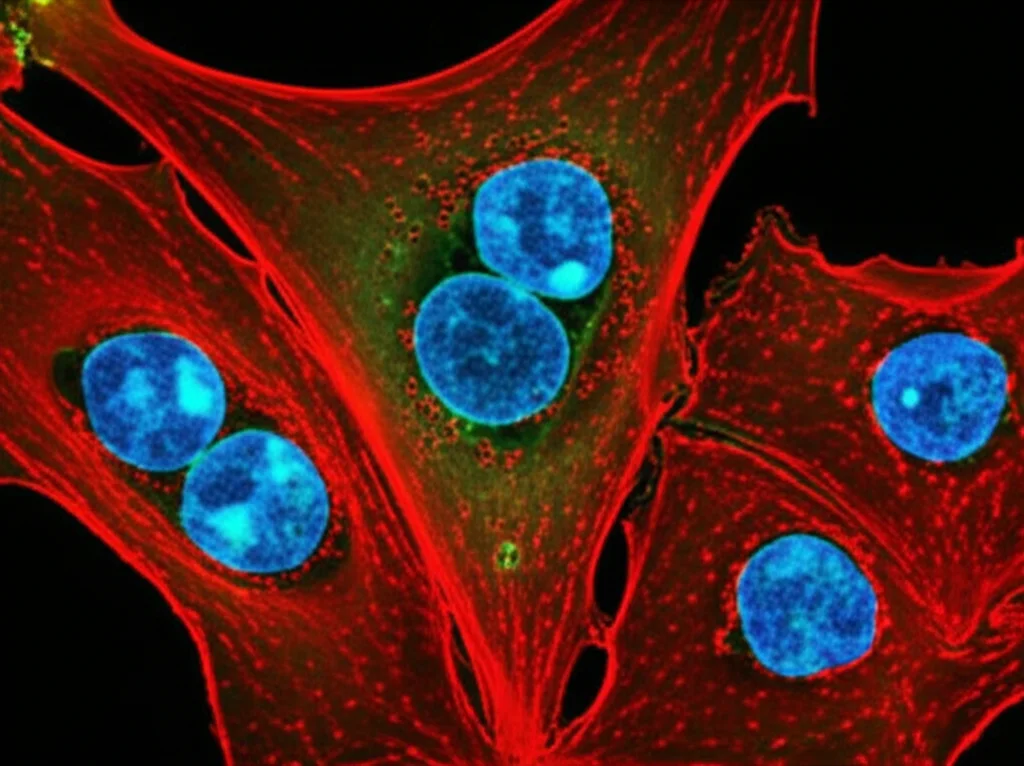

They wanted to see if tumor cells were being released locally during the procedure and if that local release meant more CTCs were showing up systemically in the peripheral blood. To find these sneaky tumor cells, they looked for cells that expressed epithelial keratin (like prostate cells) but *lacked* CD45, which is a marker for white blood cells. Basically, they were looking for non-blood cells floating in the blood.

The Tale of Two Detection Methods

Now, finding CTCs in peripheral blood can be tricky because they’re rare little things. To boost their chances, the researchers used *two* different methods to capture CTCs from the peripheral blood:

- The CellSearch System: This one grabs cells based on a surface marker called EpCAM, which is common on many epithelial cells, including prostate cancer cells.

- The Parsortix System: This method captures cells based on their size and squishiness, which is great because some tumor cells might lose that EpCAM marker if they’re changing shape (undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition, or EMT).

Turns out, using both methods together was way better than using just one. The Parsortix system alone found more positive cases (32%) compared to CellSearch (16%). And when they combined the results? They got an even more comprehensive picture.

The Big Reveal: Local vs. Systemic

Here’s where it gets really interesting. When they compared the number of those Keratin+/CD45- cells in the prostatic plexus blood versus the peripheral blood, the difference was *huge*. They found a median of 97 cells per 7.5 ml in the prostatic plexus blood compared to just 2 cells per 7.5 ml in the peripheral blood. That’s a massive difference! It strongly suggests that the surgery *does* lead to a considerable local release of cells into the blood vessels right there around the prostate.

They found these cells in the prostatic plexus blood in a whopping 85% of patients. In the peripheral blood, even with the combined methods, they found CTCs in 42% of patients. So, while peripheral CTCs are definitely present in many patients undergoing surgery, the local area is just swimming with them by comparison.

But Do They Correlate? And Do They Matter (Yet)?

Here’s the twist: despite finding way more cells locally, there wasn’t a significant correlation between the number of cells in the prostatic plexus blood and the number of CTCs in the peripheral blood from the same patient during surgery. It’s like the local flood doesn’t necessarily cause a proportional ripple effect systemically at that exact moment.

They also looked at whether the presence of these cells (either locally in the plexus or systemically as CTCs) was linked to how the patients did after surgery, specifically looking for biochemical relapse (when PSA levels start rising again). For this study, with a median follow-up of about two years, they didn’t find an association between the presence or number of these cells (even cell clusters found in the plexus blood) and biochemical relapse.

What *was* associated with peripheral blood CTCs? Higher PSA levels at the initial diagnosis. This aligns with other studies suggesting that higher tumor burden might mean more cells are already trying to escape.

Are They Tumor Cells or Just Normal Ones?

Okay, so they found a bunch of Keratin+/CD45- cells. But are they all cancer cells? Or are some just normal prostate epithelial cells that got dislodged during the surgery? This is a crucial question.

To figure this out, they did some fancy genetic analysis (single-cell genome-wide sequencing) on a subset of these cells from both the plexus and peripheral blood. They looked for copy number alterations (CNAs), which are changes in the amount of DNA in different parts of the genome – often a hallmark of cancer cells.

And guess what? They found CNAs in a good number of the cells they analyzed from both locations. Using a classifier based on known cancer and normal genomic profiles, they were able to identify that *some* of these cells were indeed tumor cells, and some even had genomic profiles similar to metastatic cancers. However, they also classified some as likely normal epithelial cells, suggesting surgery can dislodge both.

So, What Does It All Mean?

Here’s the takeaway from this pioneering study:

- Prostatectomy *does* cause a significant local release of epithelial cells, including identifiable tumor cells, into the prostatic plexus blood.

- Combining different CTC detection methods (like EpCAM-based and size-based) is important for capturing a broader range of CTCs in peripheral blood.

- While peripheral CTCs were linked to higher initial PSA, neither the local cell release nor the peripheral CTCs were associated with biochemical relapse in the relatively short follow-up period of this study.

- The lack of correlation between local release and peripheral CTCs during surgery might be due to factors like rapid dilution in the bloodstream or quick clearance of these cells.

This study is the first to really shine a light on what’s happening right at the surgical site. It confirms our suspicion that surgery can mechanically release cells. The big puzzle now is understanding the *fate* and *clinical significance* of these locally released cells. Do they survive? Do they cause problems down the line? Or are they mostly harmless or quickly cleared?

Looking Ahead

This work opens up some exciting avenues for future research. We need longer follow-up studies to see if that local cell release eventually impacts patient outcomes years down the road. We also need to learn more about the biology of these specific cells released during surgery. Could different surgical techniques affect the amount of release? Could peri-operative treatments (like drugs that might prevent cells from settling in new places) make a difference?

It’s clear that understanding the dynamics of tumor cell dissemination, both before and during treatment, is key to improving how we manage prostate cancer. This study gives us a crucial first look at the local scene during surgery and highlights that there’s still much to uncover about these traveling cells.

Source: Springer