Unlocking the Doors to Hearing: Finding New Ways to Protect Against Drug Damage

Hey there! Ever thought about how you hear the world or keep your balance?

It’s pretty amazing, right? A lot of that magic happens thanks to tiny, specialized cells in your inner ear called sensory hair cells. Think of them as super sensitive microphones that translate vibrations and movements into electrical signals your brain understands. And right at the heart of this process are these crucial little doorways called mechano-electrical transducer (MET) channels. They’re mainly made up of proteins called TMC1 and TMC2.

Now, here’s a bit of a bummer. While these channels are essential for hearing, they can also be a pathway for trouble. Certain life-saving drugs, like some antibiotics (aminoglycosides) and chemotherapy agents (cisplatin), can actually sneak into these hair cells through the very same MET channels. When that happens, it can seriously mess up your hearing and balance, sometimes permanently. It’s a tough trade-off: treat a serious illness, but risk losing your hearing.

The Big Challenge: Finding the Right Key

For a long time, we haven’t really understood *exactly* how small molecules interact with these TMC proteins. It’s like trying to pick a lock when you don’t know what the key looks like or where the tumblers are. This lack of detailed knowledge has made it super tricky to find new drugs that could potentially block these harmful substances from entering the hair cells, essentially acting as protectors for your hearing.

Our Clever Plan: A Digital and Lab Adventure

So, my colleagues and I (okay, the brilliant researchers behind this study!) decided we needed a smarter way to tackle this. We came up with a cool strategy that mixes high-tech computer modeling with real-world lab experiments. Our plan was to:

- Build a detailed 3D model of the TMC1 channel complex (including its buddies CIB2 and TMIE).

- Use computer simulations to see how it moves and where potential “sticky spots” or binding sites might be.

- Figure out the essential “features” a molecule needs to have to interact with TMC1 (that’s pharmacophore modeling!).

- Go on a massive digital treasure hunt, screening millions of compounds based on those features.

- Test the most promising candidates in actual inner ear tissue from mice to see if they really work.

Building Our TMC1 Map

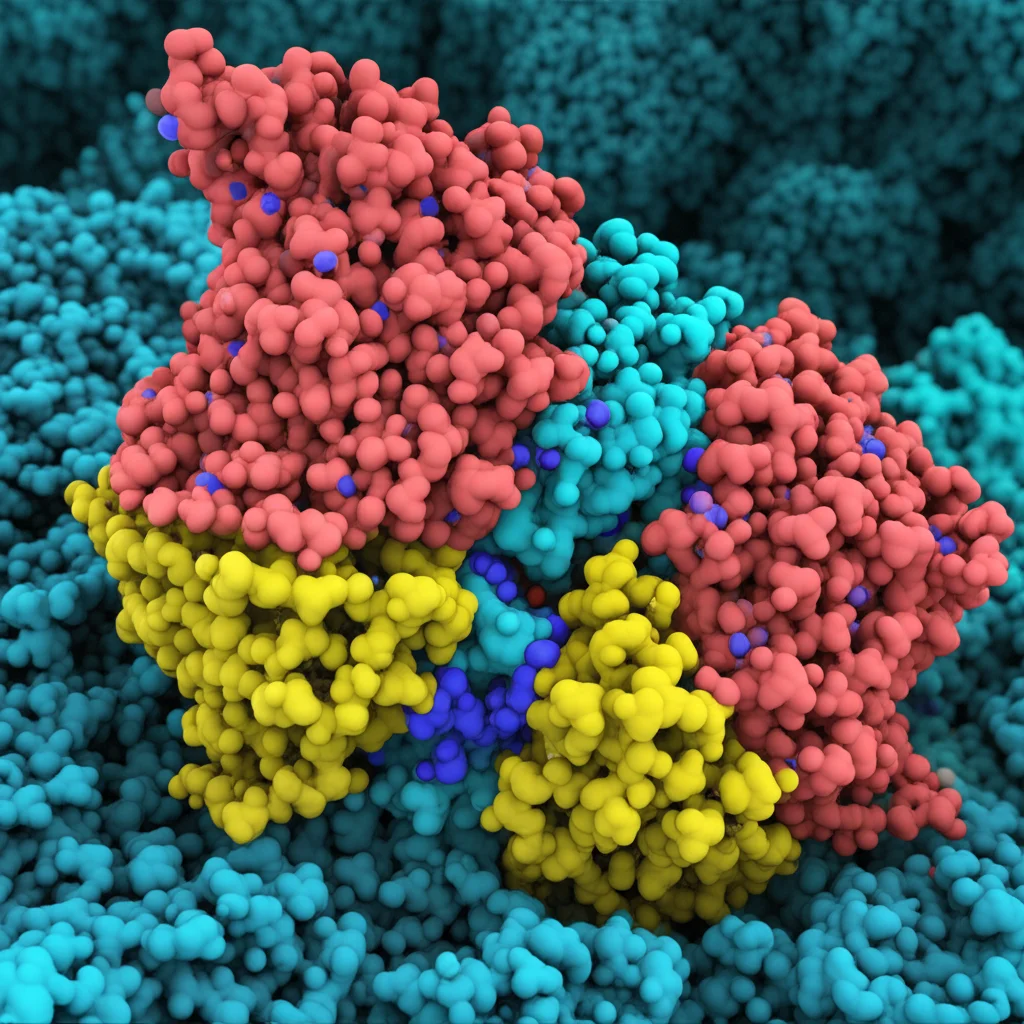

First things first, we needed a really good map of the TMC1 channel. We used fancy tools like AlphaFold2 to predict the 3D structure of the mouse TMC1 protein, along with its partners CIB2 and TMIE. Think of this complex as the whole MET channel machinery. We then put this model into a simulated cell membrane environment, complete with water and ions, and let it wiggle around in what we call molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. It’s like watching a tiny biological machine in action on your computer screen.

These simulations helped us understand how the TMC1 channel behaves, how stable it is, and importantly, what the “doorway” or pore looks like. We used a tool called HOLE analysis to measure the pore’s shape and size. We found it has a sort of winding cavity, with wider spots at the top (extracellular side) and bottom (intracellular side) and a narrower part in the middle. Crucially, we saw that phospholipid molecules (parts of the cell membrane) actually move into the pore cavity, forming a kind of “sidewall.” Water molecules and ions also hang out in there, making it a hydrated environment. This detailed view gave us a great idea of where potential drug molecules might want to bind.

Finding the Right Features: The Pharmacophore Key

Next, we looked at a bunch of compounds already known to block the MET channel, even if we didn’t fully understand *how*. We analyzed their structures to find common features – like maybe they all have a spot that can accept a hydrogen bond, or an aromatic ring, or a positive charge. We used software to build 3D “pharmacophore” models representing these essential features. It’s like creating a template for the perfect key.

Our top model, which we called APRR, suggested that a good MET channel blocker likely needs a hydrogen bond acceptor, a positively charged group, and two aromatic rings. This makes sense, as many known blockers have a protonatable nitrogen atom that can become positively charged, which seems important for blocking TMC1 activity.

The Great Digital Search

With our pharmacophore “keys” in hand, we went searching through massive databases of chemical compounds. We looked at over 230 million non-FDA-approved compounds and nearly 1800 FDA-approved drugs. We used computational screening methods to find molecules that matched our pharmacophore models. It was like sifting through a mountain of potential keys to find the ones that looked like they might fit our TMC1 lock.

This process narrowed down the possibilities significantly. We ended up with a few hundred promising candidates from the non-FDA library and a few dozen from the FDA-approved list. We even found carvedilol, an FDA-approved drug, matched our models, which was exciting because it was already known as a MET channel blocker but wasn’t in our initial training set! This told us our screening method was on the right track.

Predicting Where They Stick: Docking and Binding Energy

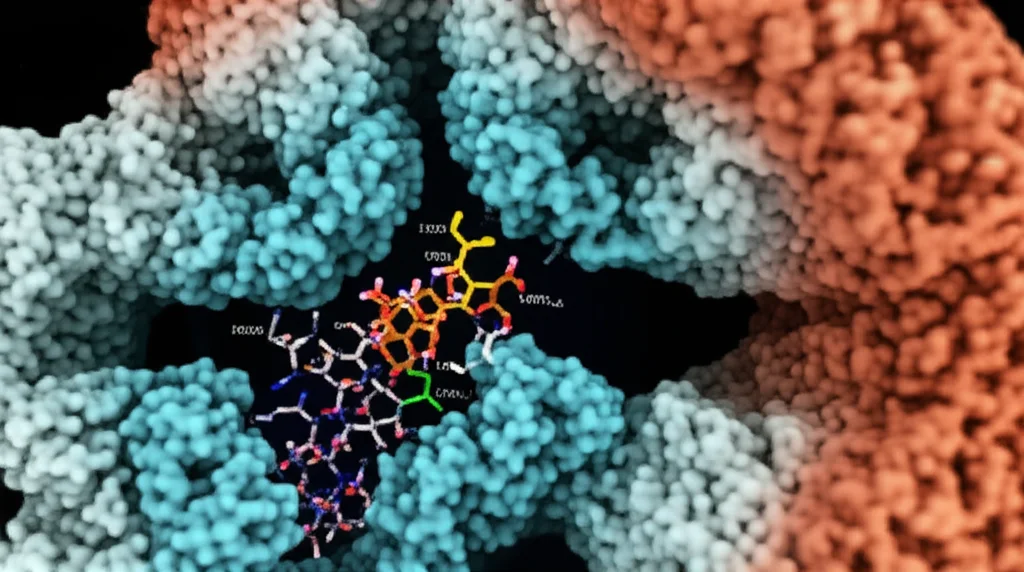

Okay, we have our potential keys. Now, where do they actually fit in the TMC1 lock, and how strongly do they bind? We used molecular docking simulations to predict how these compounds would fit into the TMC1 pore cavity. We looked for the best “poses” or orientations of the molecules within the pore. We also used a method called MM-GBSA to estimate the binding energy – basically, how “happy” the molecule is to be stuck there.

Our docking results showed that compounds tend to bind in three main areas within the pore: the top, middle, and bottom sites. We identified specific amino acid residues (the building blocks of the protein) in each of these sites that seem important for interacting with the compounds. Interestingly, the phospholipid “sidewalls” we saw in the MD simulations also seem to play a role, potentially enhancing how strongly some compounds bind.

We looked closely at how some known blockers like FM1-43 (a dye used to study these channels), benzamil, and tubocurarine interact. They bind in different spots but often involve interactions with key residues and the phospholipids. For example, positively charged parts of the molecules often interact with negatively charged amino acids in the pore, forming what we call “zwitterionic interaction zones.” We also looked at dihydrostreptomycin (DHS), an aminoglycoside antibiotic, and predicted how it binds, finding interactions consistent with previous experiments. This gave us confidence that our predictions were pretty accurate.

Bringing it to the Lab: Experimental Validation

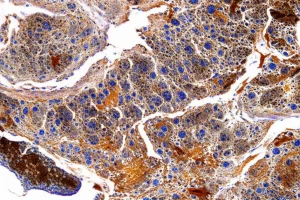

Computer predictions are awesome, but you gotta test them in the real world! We took the most promising compounds identified by our computational pipeline and tested them on actual inner ear tissue (cochlear explants) from young mice. These explants contain living hair cells with functional MET channels.

We used a fluorescent dye called AM1-43, which is similar to FM1-43 and enters hair cells through open MET channels. By measuring how much dye gets into the cells when our test compounds are present, we can see if the compounds are blocking the channel. Less dye uptake means the compound is likely blocking the MET channel.

We tested 15 commercially available compounds from our list (10 from the non-FDA library, 5 from the FDA library). And guess what? It worked! Twelve of the fifteen compounds significantly reduced the amount of AM1-43 dye entering the hair cells compared to controls. Some of the most effective blockers included:

- Several novel compounds from the non-FDA library (like ZINC24739924 and ZINC58438263).

- FDA-approved drugs like posaconazole, pyrithioxine, and cepharanthine.

This experimental validation is super important because it shows that our computational pipeline is effective at finding molecules that actually modulate TMC1 activity in a biological setting.

Beyond TMC1: Connections and Future Steps

It’s interesting that cepharanthine, one of the FDA-approved drugs we found, is also known to inhibit a related protein called TMEM16A. This suggests there might be some overlap in how these different ion channels are modulated, and our pharmacophore models might be useful for studying other related proteins too.

Our study provides a ton of new atomic-level details about how small molecules interact with the TMC1 pore. We confirmed the importance of some previously known residues (like M412, D528, D569) and identified many new ones that likely play a role in ligand binding. The idea that phospholipids are active players in this binding process is also a cool insight.

Where do we go from here? Well, this is just the beginning! We need to do more detailed experiments, like single-cell electrophysiology, to really understand how potent these new compounds are and exactly how they affect the channel’s function. We also want to use techniques like site-directed mutagenesis to change specific amino acids in the TMC1 pore and see if it affects the binding of these compounds, further validating our predictions about the key interaction sites.

We also need to think about TMC2. While TMC1 is the main player in mature hair cells, TMC2 is present during development. Our current model focuses on TMC1, but future work could explore how these compounds interact with TMC2 or if they are selective for one over the other. This is especially important for protecting the hearing of young patients.

Wrapping it Up

So, what’s the big takeaway? We’ve developed and validated a powerful pipeline that combines sophisticated computer modeling with experimental testing to find new molecules that can modulate the TMC1 channel. We identified specific structural features (our pharmacophore key) that seem important for blocking the channel and pinpointed potential binding sites within the TMC1 pore, highlighting the crucial roles of specific amino acids and even phospholipids.

This work has successfully identified several novel compounds and existing FDA-approved drugs that can reduce the entry of substances into hair cells via the MET channel. This is a huge step forward in the search for otoprotective therapies – drugs that could potentially prevent the devastating hearing loss caused by necessary medications like certain antibiotics and chemotherapy.

It’s an exciting time in hearing research, and we’re hopeful that this approach will lead to the discovery of new treatments to protect this precious sense.

Source: Springer

![Macro lens, 60mm, high detail, precise focusing image of a collection of colorful, glowing 3D molecular models representing the 2-(Aryl)benzo[d]imidazo[2,1-b]thiazole-7-sulfonamide derivatives, arranged on a dark, reflective surface with artistic, controlled lighting to emphasize their complex structures and potential as antitubercular and antibacterial agents.](https://scienzachiara.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/149_macro-lens-60mm-high-detail-precise-focusing-image-of-a-collection-of-colorful-glowing-3d-molecular-models-300x150.webp)