Unlocking Super Alloys: How Strain Energy Picks the Perfect Pattern

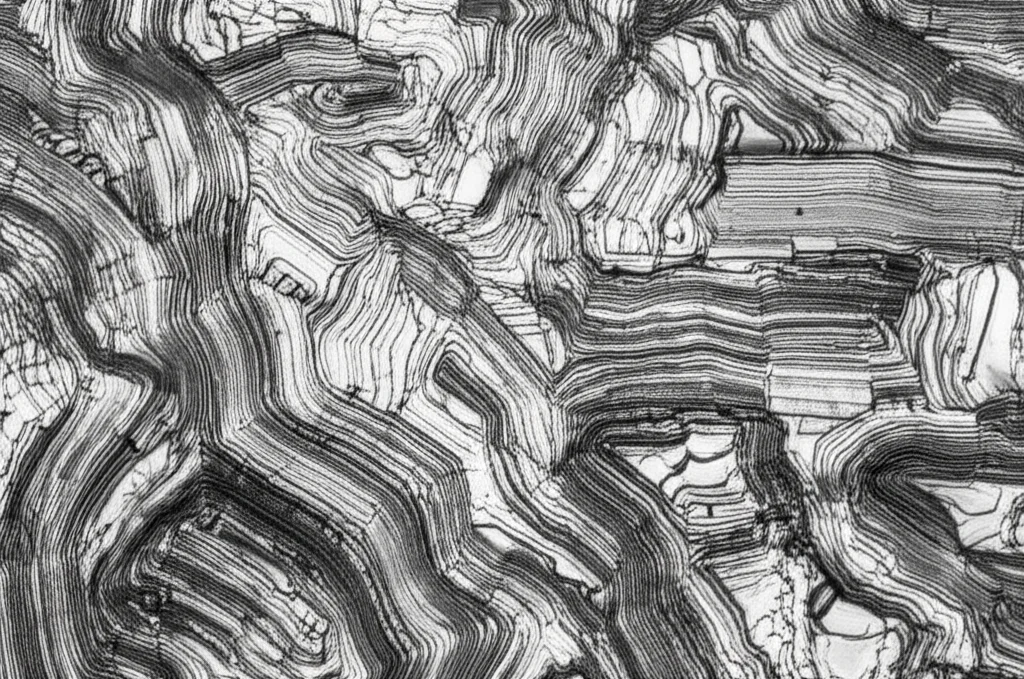

Alright, let’s talk about something pretty cool that happens deep inside some seriously tough materials. We’re diving into the world of Ti-Al alloys, the kind of stuff they use in places where things get *really* hot, like aircraft engines. These aren’t just any metals; they have this fascinating internal structure, kind of like microscopic layers or “lamellae,” made up of different crystal orientations, or “variants,” of the gamma (γ) phase.

Now, this layered structure is super important for making these alloys strong and tough, especially at high temperatures. But here’s the million-dollar question: out of all the possible ways these layers could form and stack up, how does the material *choose* which ones go where? It’s like a microscopic architectural puzzle, and the pieces are these different γ variants bumping into each other and forming boundaries.

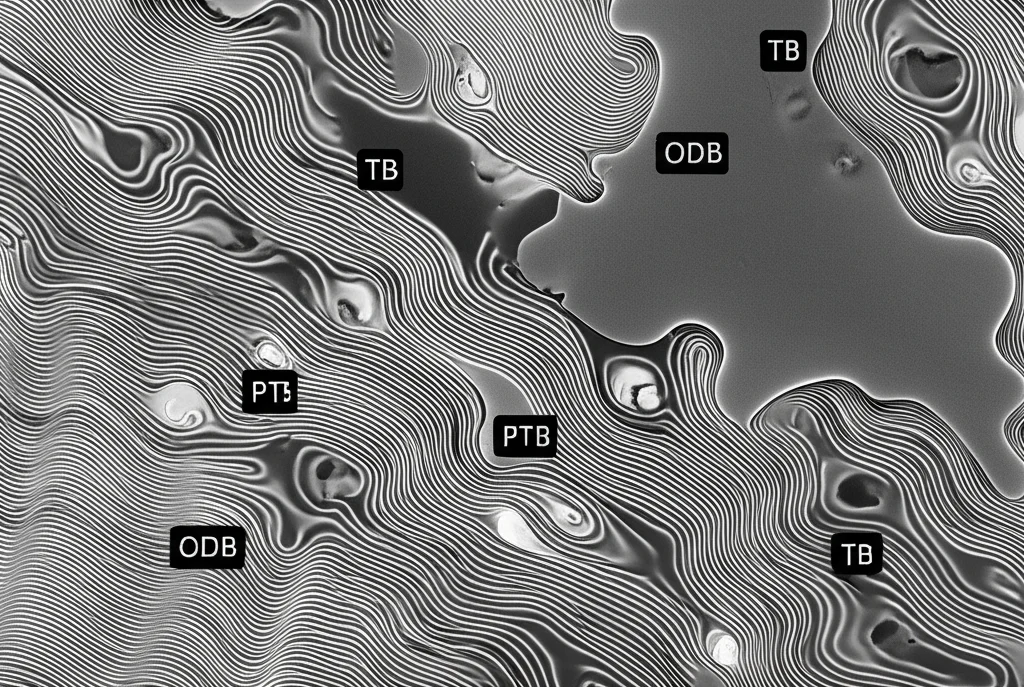

There are a few main types of boundaries (or interfaces, if you want to get technical) between these γ variants:

- Twin Boundaries (TB): Think of these as mirror images – a very low-energy, stable way for crystals to meet.

- Pseudo-Twin Boundaries (PTB): A bit more complex than TBs.

- Ordered Domain Boundaries (ODB): Another type of interface, often with higher energy.

The ratios of these interfaces inside the material matter a lot for how strong and durable it is. But figuring out *why* certain interfaces become more common during the material’s formation? That’s been a bit of a head-scratcher. Lots of things influence this “variant selection” – crystal orientation, temperature, even external stress. It’s a tiny, complex dance happening at the nano and micro-scale.

The Mystery of Variant Selection

People have been trying to crack this code for a while. Some theories focused on minimizing interface energy – basically, crystals prefer to meet in ways that require the least energy at the boundary. They figured a higher percentage of those low-energy TBs would make the whole system happier, energetically speaking. And yeah, studies did show that TBs seem to pop up a lot.

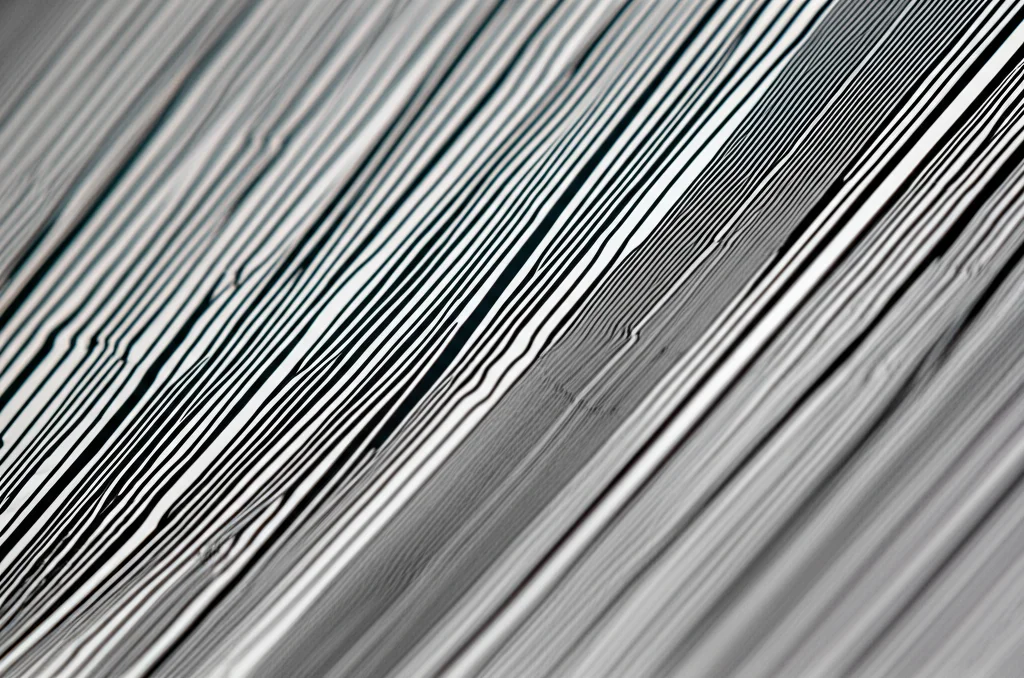

But here’s where it gets interesting: previous work mostly looked at the *interface energy* itself. What about the *elastic strain energy*? Think of strain energy as the stress built up in the material when different crystal structures or orientations don’t quite fit together perfectly. It’s like trying to fit slightly different shaped LEGO bricks together – there’s going to be some tension. Could *this* strain energy be a major player in deciding which variants get to nucleate (start forming) and grow? This study says, “Yep, hold my beer, that’s exactly what we’re going to look at!”

Enter the Phase-Field Simulation Heroes

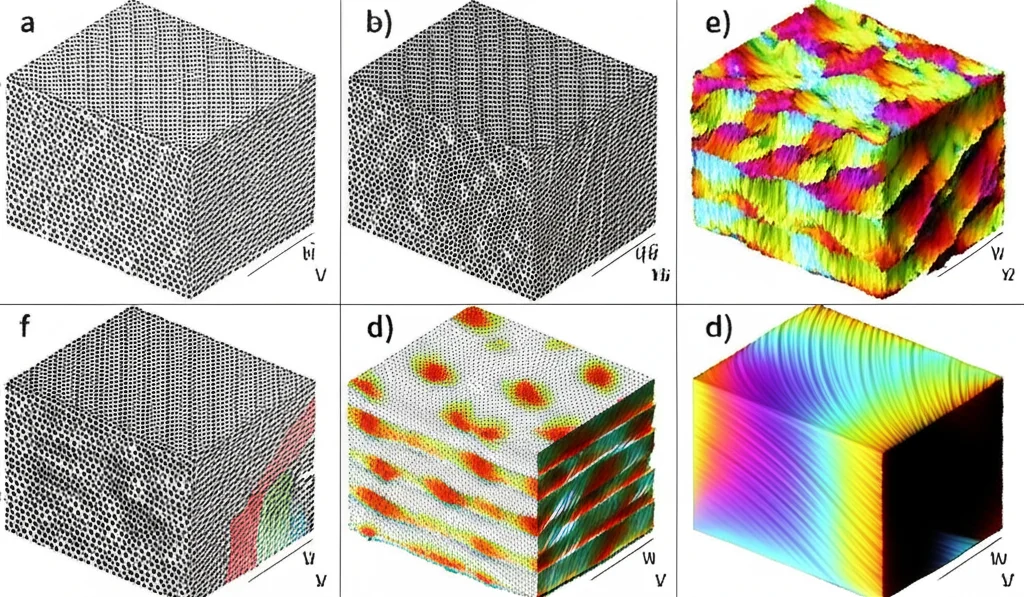

To get a real peek into this microscopic world, the researchers used something called phase-field simulations. Imagine building a detailed virtual model of the material as it forms, tracking everything from the composition of elements (like Aluminum in our Ti-Al alloy) to the crystal structure and the energies involved. This lets us watch the variant selection process unfold step-by-step, seeing how interfaces form and evolve.

They set up a simulation for a specific Ti-Al alloy (Ti-45 at.% Al) and, crucially, included the effects of both interface energy *and* elastic strain energy. They could even tweak a parameter, let’s call it ‘D’, to represent the *strength* of the elastic strain energy’s influence.

Watching the Magic Happen (in Simulation)

So, what did they see when they ran the simulations?

First, they looked at what happens with no elastic strain energy effect (D=0). The γ variants formed, sure, but they were kind of scattered and didn’t really line up into those neat lamellar layers we talked about. It was a bit of a random free-for-all.

But then, they cranked up the elastic strain energy parameter (D=0.9, 1.0, 1.1). *Voilà!* The lamellar structure started to appear. And not only that, the *type* of interfaces forming changed dramatically. As D increased, the number of TB interfaces shot up compared to PTB and ODB. It turns out, elastic strain energy isn’t just *a* factor; it seems to be a *driving force* pushing the system towards forming more TBs.

At the very early stages of nucleation, the different interface types might appear in a more random ratio (like 1:2:2 for TB:PTB:ODB in one simulation snapshot). But as the variants grow and the system evolves, the TBs take over, becoming the most frequent interface type. This matches up with what experimentalists often see in real materials.

Why TBs Are the Favorites

The simulations also helped explain *why* TBs win the popularity contest. They measured the elastic strain energy associated with each type of interface. Guess what? TBs had the *lowest* elastic strain energy. ODBs had the highest, and PTBs were somewhere in between. It’s like TBs are the most comfortable fit, creating the least stress in the material.

They also looked at the interface energy itself, and again, TBs had the lowest interfacial energy.

This is a big deal! It suggests that while interface energy plays a role, the *elastic strain energy* might be the primary driver, especially under certain conditions. The material seems to actively select variants that can form interfaces (like TBs) which minimize the overall strain energy of the system. It fits nicely with non-classical nucleation theory, which says that strain energy plays a huge role in how new phases form, especially when there’s a lattice mismatch. Forming a TB is a great way to reduce that mismatch strain.

Composition and Stability

The study also peeked at the composition – specifically, the concentration of Aluminum – at these different interfaces. They found that as the elastic strain energy increased, the Al concentration at *all* interfaces went up. It’s like the strain field pulls the Al atoms towards the boundaries. However, even with increased strain energy, the TB interfaces consistently had a *lower* Al concentration compared to PTB and ODB. This reinforces the idea that TBs are the “low energy” interfaces – they require less Al segregation to achieve stability under strain.

The stability of TBs under high elastic strain energy is particularly noteworthy. It means that when the material is under stress (or forms in a way that creates internal stress), the TB structure is the one that holds up best, further explaining why they become dominant.

The Big Takeaway

So, what did we learn from this deep dive (or rather, this simulation-based exploration)? The formation of that crucial lamellar structure in Ti-Al alloys isn’t just a random roll of the dice for variant interfaces. It’s heavily influenced, and perhaps *driven*, by the need to minimize elastic strain energy. The material preferentially selects variants that can form low-strain interfaces, primarily the Twin Boundaries (TB).

This isn’t just academic curiosity. Understanding *why* these specific structures form gives us powerful insights. If we know that elastic strain energy is the key driver, we can potentially find ways to control it during the manufacturing process – maybe through heat treatments, processing routes, or even subtle changes in alloy composition – to encourage the formation of more of those desirable TBs. More TBs mean a better, stronger, more reliable material for those demanding high-temperature jobs. It’s all about using fundamental science to build better stuff!

Source: Springer