Could Targeting This Protein Be the Key to Calming Ulcerative Colitis?

Hey there! Let’s dive into something pretty fascinating about a tough condition called Ulcerative Colitis (UC). If you or someone you know deals with this, you know it’s no walk in the park. It’s a chronic inflammatory disease that really messes with the lining of your colon, causing all sorts of unpleasantness and even increasing the risk of colon cancer down the line. Current treatments? Well, they help some people, but honestly, over half don’t get full relief, and even those who do often see symptoms come back. So, yeah, we desperately need new ideas.

The Body’s Clean-Up Crew: Efferocytosis

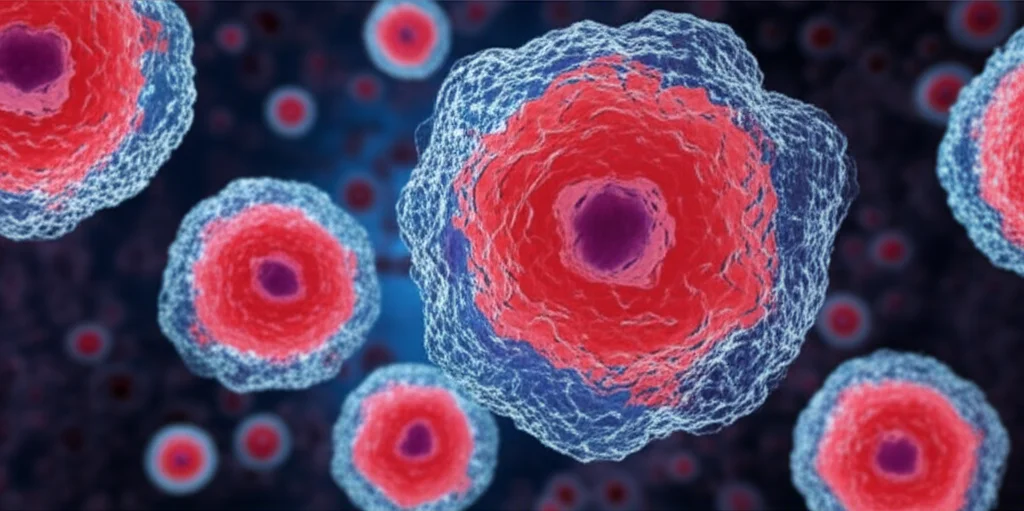

Think of your body like a busy city. Cells are constantly working, living, and eventually, well, dying. When cells die, especially in a messy way like apoptosis (a kind of programmed self-destruct), you need a good clean-up crew to get rid of the debris. This clean-up process is called efferocytosis. It’s super important for keeping tissues healthy and preventing inflammation.

Here’s how it generally works:

- Dying cells send out “find me” signals to attract clean-up cells (phagocytes).

- They then show “eat me” signals, like exposing a molecule called phosphatidylserine.

- Phagocytes recognize these signals and gobble up the dead cells.

When this clean-up system breaks down, those dead cells hang around, causing irritation and fueling chronic inflammation. And guess what? Problems with efferocytosis have been linked to inflammatory diseases, including, you guessed it, UC. Getting rid of dead cells properly can actually help calm things down and promote healing.

Enter SLC7A11: A Protein with a Role

Now, let’s talk about a specific player in this story: a protein called SLC7A11. It’s part of a big family of proteins that transport stuff across cell membranes – in this case, it swaps an amino acid called cystine from outside the cell for glutamate inside. Recent studies have hinted that SLC7A11 might actually *inhibit* that crucial efferocytosis process we just talked about, especially in immune cells like dendritic cells. If SLC7A11 is putting the brakes on the clean-up crew, and broken clean-up leads to inflammation… well, you start to see where this is going, right?

What We Found: SLC7A11 is High in UC

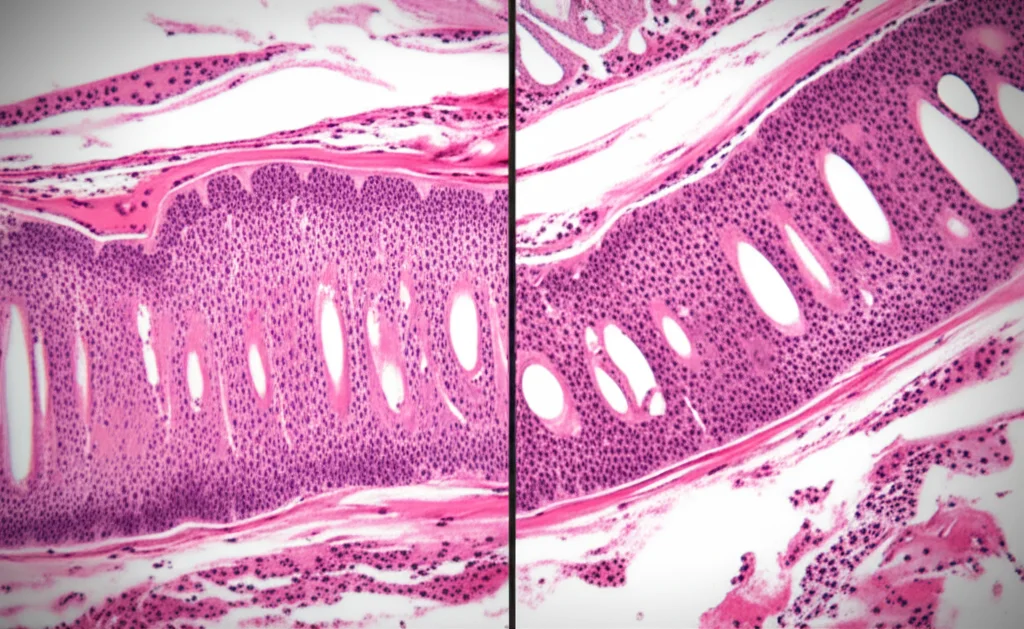

So, we decided to take a closer look at SLC7A11 in the context of Ulcerative Colitis. We examined colon tissues from UC patients and compared the inflamed areas to the non-inflamed parts. What did we see? SLC7A11 expression was significantly *higher* in the inflamed regions. This was particularly noticeable in dendritic cells, those important immune cells that are part of the clean-up crew. This finding immediately suggested that SLC7A11 might be playing a role in the inflammation seen in UC.

Testing the Theory: Mouse Models

To really test if targeting SLC7A11 could help, we moved to mouse models of colitis. We used mice where the colitis was induced (like giving them DSS, a chemical that causes inflammation similar to UC) and compared them to mice where SLC7A11 was either genetically reduced (knockout mice) or targeted with a special antibody we developed (called 1A4).

The results were pretty encouraging!

- Mice with reduced SLC7A11 or treated with the 1A4 antibody showed significantly less weight loss compared to untreated mice with colitis.

- Their disease activity index (a score based on symptoms) was lower.

- Their colons were less shortened (a sign of less damage).

- Their intestinal barrier function was better preserved (less “leaky gut”).

- Even their spleens, which often enlarge with inflammation, were less affected.

In fact, targeting SLC7A11 seemed to perform better than sulfasalazine, a traditional UC treatment, in some aspects of the mouse model. We also saw less tissue damage and fewer signs of excessive cell death (apoptosis) in the colons of mice where SLC7A11 was targeted. This really suggested that reducing SLC7A11 levels was helping to calm the inflammation and protect the gut lining.

Fixing the Gut Barrier: It’s About More Than Just Clean-Up

The intestinal lining isn’t just a passive barrier; it’s a dynamic structure held together by “tight junctions” – like the mortar between bricks. In UC, these junctions get messed up, leading to increased permeability (that “leaky gut” idea). We used a cell model (Caco-2 cells, which act like intestinal lining cells) and exposed them to inflammatory signals (TNF-α and IFN-γ) that mimic UC conditions. This damaged their barrier function.

When we added our 1A4 antibody (targeting SLC7A11) to these damaged cells, it significantly helped restore the barrier integrity. The cells became less leaky. While the overall *amount* of tight junction proteins didn’t change much, their *localization* – where they were positioned to hold the barrier together – improved. We found that targeting SLC7A11 seemed to do this by interfering with a signaling pathway called MLCK-P-MLC, which is known to mess with the structure of the cell lining. So, it looks like SLC7A11 isn’t just involved in efferocytosis; it might also directly weaken the gut barrier through this other pathway.

Boosting the Clean-Up Crew: The ERK1/2 Connection

Now, back to efferocytosis. We specifically looked at how targeting SLC7A11 affected the ability of dendritic cells (those key immune cells) to clear apoptotic cells. Using dendritic cells derived from mouse bone marrow, we saw that both genetically reducing SLC7A11 and treating the cells with the 1A4 antibody significantly *increased* their ability to gobble up dead cells. The clean-up crew became much more efficient!

We then dug into *how* this was happening. Previous studies pointed to the ERK1/2 pathway as being important for efferocytosis. When we targeted SLC7A11 in the dendritic cells, we saw increased activation (phosphorylation) of ERK1/2, as well as an increase in a marker associated with efferocytosis (CD36). To confirm that ERK1/2 was the key, we used a specific inhibitor to block the ERK pathway. When ERK1/2 was blocked, the boost in efferocytosis caused by targeting SLC7A11 disappeared. This strongly suggests that targeting SLC7A11 promotes efferocytosis in dendritic cells *specifically through* activating the ERK1/2 signaling pathway.

Putting It All Together: A New Hope for UC?

So, what does this all mean? Our findings paint a picture where SLC7A11 is elevated in the inflamed colon of UC patients. This elevated SLC7A11 seems to contribute to the disease in at least two ways:

- It might directly compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier, possibly by messing with the MLCK-P-MLC pathway.

- It inhibits the crucial efferocytosis process in immune cells like dendritic cells, preventing the proper clean-up of dead cells and thus fueling inflammation.

By targeting SLC7A11, we saw improvements in both these areas in our models – the barrier function was better preserved, and the efferocytosis (via the ERK1/2 pathway) was enhanced.

This research is super exciting because it points to SLC7A11 as a really promising new target for treating Ulcerative Colitis. Instead of just trying to suppress the general inflammation, we might be able to tackle some of the underlying problems: fixing the leaky gut and helping the body clear inflammatory debris more effectively. It’s still early days, of course, but these insights open up a whole new avenue for developing therapies that could potentially make a real difference for people living with UC.

Source: Springer