Unlocking Ancient Secrets: The Ritual Landscapes of the Tangier Peninsula

A Gateway to the Past

Let me tell you, there’s something truly special about the Tangier Peninsula. Tucked away on the northwestern tip of Africa, right where the Atlantic kisses the Mediterranean and Europe is just a stone’s throw across the Strait of Gibraltar, this place has been a buzzing crossroads for millennia. Imagine, since the Late Stone Age, it’s been a bridge, a meeting point, a place where ideas, people, and practices flowed back and forth.

And what did all this connectivity leave behind? Well, from roughly 3000 to 500 BC, it created a simply incredible tapestry of burial traditions, ritual spots, mysterious monuments, and rock art. It’s a mosaic that completely ignores the modern borders we’ve drawn on maps.

Now, I have to be honest, studying this period in North Africa, west of Egypt, is a bit of a challenge. Despite folks looking into it for over 200 years, it’s still one of the least understood parts of the Mediterranean. Why? Well, life today moves fast. Urban sprawl, farming, political ups and downs, and sadly, a lot of looting have taken their toll. These ancient sites, especially cemeteries and monuments with cool artifacts, are prime targets for treasure hunters. We’re talking about “Souassa” in Morocco, who’ve been at this since medieval times – and it’s still a big problem.

Add to that, during the colonial era, archaeology here often focused heavily on the Roman period, kind of giving the cold shoulder to everything that came before. The big exception was the investigation of dolmen-like burials, but even that only scratches the surface. This has left us with a bit of a patchy understanding, using old labels like “Copper Age” or “Bronze Age” that might not even fit the local story perfectly. And finding settlements from this time? That’s another puzzle piece that’s often missing, making it tough to see the whole picture of how these ancient societies lived.

That’s why the Tangier Peninsula is such a fantastic place to focus on. Its unique location makes it key to understanding North Africa’s ancient ritual and burial scenes. Plus, while it’s been researched, its funerary and ritual landscapes haven’t gotten the deep dive they deserve. What’s really cool is the sheer variety here – caves, pits, cists, tumuli, rock art, standing stones – you name it, it’s got echoes in both Atlantic Europe and the Sahara.

Instead of looking at cemeteries here and rock art there, we’re trying to see them as part of one big, interconnected symbolic and ritual landscape. Our fieldwork, part of the Tahadart and Kach Kouch Archaeological Projects, is all about digging into these social, cultural, and economic dynamics and seeing how they link up with the wider Mediterranean and Atlantic worlds.

Mapping the Ancient Landscape

Think of the Tangier Peninsula as a chunky triangle of land, about 8000 sq km, facing Spain across that narrow Strait. It’s bordered by the Atlantic and Mediterranean, with rivers defining its southern edges. Geographically, it’s diverse – sandy plains and big rivers on the Atlantic side, rugged mountains and valleys on the Mediterranean side.

In ancient times, the coastlines were a bit different. The Atlantic side had open bays and lagoons that might have made coastal travel tricky, perhaps encouraging boat use or inland routes. Using fancy GIS software, we can map out potential communication corridors and crossroads based on where ancient settlements were found. We targeted a couple of these crossroads for our fieldwork, and boy, did they deliver! One spot, Crossroad A, gave us exciting new finds of cemeteries, standing stones, and rock art. Another, Crossroad D, is revealing details about settled life, like the amazing farming settlement at Kach Kouch, which was occupied for ages (late third to early first millennia BC) and shows connections far and wide.

The close proximity to southern Iberia, just a few kilometers away, meant maritime connections were likely happening since way back. We see shared artifacts across the Strait, hinting at these links. The arrival of farming around 5400 BC, coming from the Western Mediterranean, also suggests increasing sea travel. Later, around 4500 BC, there seems to be a Saharan influence, maybe due to environmental changes pushing people around.

While the period around 3000 BC (the Copper Age in Iberia) is still a bit of a mystery box in northwest Africa, finds of Beaker pottery and metal objects suggest there was definitely something happening and connections across the Strait continued. The Bronze Age (roughly 2200–800 BC in Iberia) is even less understood here, but new radiocarbon dates, like the one we got, are slowly filling in the blanks. Understanding this period is super important for figuring out what happened next, during the Mauretanian 1 phase (c. 800–500 BC), which saw the rise of Phoenician settlements and increasing connectivity.

Basically, this region wasn’t some isolated corner. It was smack-dab in the middle of a huge network, not just within the Mediterranean but also the bustling inner Atlantic. And as we’re finding, this connectivity is totally reflected in the ancient monuments, rock art, and rituals from 3000 to 500 BC.

Ancient Ways of Death and Memory

The way people dealt with death in the Tangier Peninsula, from the earliest times right through to 500 BC, tells us a lot. The oldest burial we know of is in Hattab II Cave, dating back to the Late Stone Age. It’s a simple inhumation with some grave goods, showing that burial practices here have deep roots.

In the Early Neolithic (c. 5400–4500 BC), people were buried in both caves and open-air sites, like near the ancient bay of Tahadart. The Middle and Final Neolithic (c. 4500–3000 BC) are less clear in the peninsula itself, but elsewhere in northwest Morocco, caves and large open-air cemeteries were used. Sites like Rouazi-Skhirat, with around 100 burials, show these practices were happening on a significant scale, sometimes including distinctive pottery like Achakar Ware.

Now, let’s jump to our core period, 3000 to 500 BC. The early part, the third millennium BC, is still pretty blank in the Tangier Peninsula, except for a single intriguing tooth from the Achakar Caves that hints at activity around 2470–2240 BC. Cave burials are definitely present, like at Benzú and Hafa II, dating from the late third to mid-second millennia BC. These caves are near Djebel Moussa, a really prominent spot linked to the Pillars of Hercules legend, and they mirror burials across the Strait in Gibraltar. It makes you wonder if this area was seen as a symbolic maritime space, or if it just shows a long tradition of using caves for burials.

Pit burials were also a thing, with bodies placed in simple pits, sometimes covered by slabs. Some might even have been part of larger cemeteries, similar to what we see across the Strait. Our dive into the archives of Cesar Montalban, an archaeologist from the 1940s, revealed previously unknown pit burials on the Achakar plateau, right above those famous caves. These contained multiple individuals and pottery, and the style of the pots suggests a date in the third to second millennia BC. Pit burials are common across North Africa and Iberia during this time, so it’s another link in the chain.

Then, from at least the late third millennium BC, a new type of burial pops up: cist burials. These are more monumental – built with large stone slabs – requiring a real investment of time and effort. This might suggest communities were becoming more settled and maybe had clearer control over their land.

Early French researchers in North Africa called similar megalithic burials “dolmens,” connecting them to European ones. But some, like Camps, argued that the Tangier Peninsula’s cists were different – older, distinct in shape, and linked to Iberia and the Atlantic world, perhaps arriving with things like Beaker pottery. Dolmens further east in the Maghreb seem to be later and linked to Italy and Sardinia. It’s a complicated picture, and honestly, the lack of dates and detailed research makes it hard to be sure about the origins of these structures across North Africa.

Back in the Tangier Peninsula, cist burials were first noted way back in the 1870s. Ponsich did major work in the 1960s, classifying them and suggesting differences between Bronze Age and Iron Age cists based on how they were built and what was found inside. Bronze Age cists are typically trapezoidal boxes of four big vertical slabs with a capstone, often with a unique crescent-shaped stone pile outside the eastern side. They look a lot like cists in southwestern Iberia, though that crescent feature is unique to North Africa. They usually contain one person, buried in a flexed position, sometimes sprinkled with ochre, and accompanied by pottery, tortoiseshell, and metal items like awls or daggers that have parallels in Early Bronze Age Iberia.

Intriguingly, some cists contain only grave goods, or are completely empty. This isn’t just looting; it happens in Iberian cists too, leading to debates about whether they were intentionally built as cenotaphs (empty tombs honoring someone buried elsewhere). In the Tangier Peninsula, finding empty tombs next to ones with remains suggests it was a cultural practice, assuming they weren’t looted beforehand.

Continuity and New Forms

What’s fascinating is how Iron Age burial traditions (eighth to fifth centuries BC) in the Tangier Peninsula show continuity. Cists are still used, often near older Bronze Age ones. The earliest Iron Age cists even look similar, but they start adding a stone pile on top, like a mini-tumulus. Over time, the stone slabs get replaced by squared stone walls, and the shape becomes more rectangular. Burial practices stay similar – flexed bodies, ochre – but the grave goods change, including wheeled pottery, iron objects, decorated ostrich eggshells, and fancy eastern jewelry. Some Iron Age cemeteries, like Djebila and Ain Dalia Kebira, are huge, with over 80 or 100 cists, suggesting larger communities.

Alongside the Iron Age cists, a totally new burial type appears: hypogaea, which are rock-cut tombs. These show up on the Achakar plateau, a spot that clearly had long-standing ritual significance. These hypogaea look very similar to tombs found in southern Iberia and other Phoenician sites in the Mediterranean around the seventh-sixth centuries BC. But here’s the kicker: the stuff found inside is the same as in the contemporary cist graves. This makes you wonder if the people buried in these foreign-looking tombs were actually locals, or perhaps people of mixed background, adopting a new tomb style but keeping local burial practices and grave goods.

Then there are tumuli and bazinas – mounds of earth or stone, sometimes shaped like truncated pyramids. These are the most widespread burial types across North Africa, from the Mediterranean coast down into the Sahara. Camps thought they had a deep local North African origin, unlike other built tombs. In Morocco, they’re common along the Atlantic coast and spread south. While often dated to the first millennium BC, the presence of older tumuli in the Sahara and Iberia, and the fact that some tumuli cover cists in both North Africa and Iberia, make me think they might be older here too, perhaps evolving from or alongside the cist tradition. They were likely monumental burials, maybe reflecting growing social differences.

Mzoura: A Monumental Mystery

Speaking of monuments, Mzoura is a real head-scratcher. About 40 km southwest of Tangier, it’s a massive site with several groups of standing stones. The most famous part is the “Cromlech of Mzoura,” a circle of 176 standing stones, some over 5 meters tall, surrounding a huge tumulus, 6 meters high and 55 meters wide. Early excavations in the 1930s found retaining walls inside the tumulus, described as “straight ashlar-built walls,” and even a Libyan inscription, suggesting a later date, perhaps the Mauretanian period. There’s conflicting info about a cist burial at the center, but the excavator did find small stone structures (trilithons), a pit with charcoal, and a burial outside the mound.

More recent studies suggest the standing stones were shaped with stone tools, while the ashlar blocks in the tumulus walls used metal tools, hinting at two construction phases: an earlier one for the stones, and a later one (mid-first millennium BC) for the tumulus, likely as a burial for someone important. But those standing stones don’t really have parallels in North Africa in the first millennium BC; they look more like monuments from third millennium BC Atlantic Europe. Plus, there are other smaller groups of standing stones at Mzoura without tumuli.

It’s a frustrating lack of data, but it makes me think Mzoura might have been a significant gathering place since way back, perhaps reused later by elites who wanted to link themselves to an ancient, powerful spot. Its location on a major route, surrounded by cist and tumuli cemeteries, definitely places it within a broader ancient ritual landscape.

New Discoveries in the Field

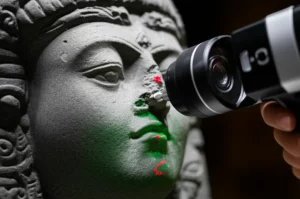

Our fieldwork in the northwestern Tangier Peninsula has been exciting. We surveyed a major crossroads identified by GIS and found three previously unknown cemeteries: Daroua Zaydan, Oulad Zin, and Oued Ksiar. Daroua Zaydan is a single cist. Oulad Zin has a tumulus and several cists on neighboring hills. Oued Ksiar is the biggest, with two tumuli and multiple clusters of cists spread across five hills. Sadly, all show signs of extensive looting, which is a stark reminder of the threats to these sites.

We decided to excavate the single cist at Daroua Zaydan, partly to minimize attention on the larger sites. It was a trapezoidal cist built with sandstone slabs, covered by a large capstone, with a crescent-shaped pit outside the eastern side – just like those described by Ponsich at El Mers! Inside, we found only a few flint flakes. No human remains *in* the cist, but scattered human bones were found just outside, likely due to past looting.

And here’s the breakthrough: we got a radiocarbon date from one of those bones! It dates the use of this cist to 2119–1890 BC. This is the *first* radiocarbon date for a cist burial in northwestern Africa, and it places this tradition firmly in the Early Bronze Age, aligning with similar cist burials in neighboring Iberia. This date helps explain why we haven’t found earlier Beaker pottery in cists and why the metal objects found in them look like items from Iberian Early Bronze Age contexts. Isotopic analysis on the bone also tells us the person had a diet mostly of land animals and plants, with only a little bit of seafood. We’re still waiting on DNA results, which could be incredibly revealing about who these people were.

We also revisited known cemeteries. The big Bronze Age cemetery at El Mers seems completely gone due to urban growth. El Mriès and Jebila are badly damaged. At El Mriès, an excavator basically dug away a huge part of the hill, destroying many burials but exposing lots of pottery. We collected some decorated sherds that have parallels in other local sites and caves, providing rare examples of pottery from cist cemeteries. We also found a pure copper awl. And digging through Montalban’s archives, we found a report from 1952 mentioning a dagger/halberd and Palmela points looted from El Mriès. This doubles the known daggers/halberds from the region and highlights just how much information has been lost to looting.

Beyond burials, standing stones are another part of this ritual landscape. We found two previously undocumented ones along what seem to be ancient routes. One is a big pointed stone over 2.5m tall, located in a key corridor. The other is smaller but strategically placed overlooking an inland road. Their position near major cemetery concentrations suggests they were important markers in the landscape, though many might have disappeared over centuries of farming.

Rock Art and Sacred Places

Caves and shelters have long been seen as sacred in North Africa. The “Idol’s Cave” in the Achakar complex, for example, yielded hundreds of clay figurines from later prehistory, perhaps linked to solar cults or fertility rituals. Rituals in caves also include rock art – paintings, cup marks, carvings. Before our work, Magara Sanar 1 was the only known painted shelter in northwest Morocco, with figures painted mainly in red, showing parallels with Late Stone Age art in southern Iberia. Paintings are more common further south in Morocco, but less so in the north.

Engraved cup marks are found in open-air sites and on Mzoura’s standing stones in the Tangier Peninsula. They’re also found elsewhere in Morocco and across the Strait. Other carvings include lines and symbols, like those at Marsa IV shelter. Some engraved standing stones (stelae) further south near Rabat depict human figures and concentric lines, different from Iberian stelae and of uncertain date.

Our survey hit the jackpot, finding twenty-four previously unknown rock art sites! Nineteen are clustered around a major crossroads, and five are near Magara Sanar 1. We found open-air cup marks, shelter cup marks, and sixteen painted rock shelters. This totally changes the picture, showing the western Rif mountains are a major area for rock art study. The styles show influences from both Iberian schematic art and sites further south in Morocco.

We see motifs shared with southern Iberia (lines, dots, anthropomorphs) and others with the Moroccan Atlas and the Sahara (squares with dots, certain lines). Some sites might be very old, with dotting compositions similar to Late Stone Age examples in Magara Sanar 1 and Iberia. But others show later elements, like Arabic inscriptions, proving these places were used for ritual activities into historical times.

The presence of cup marks on Mzoura’s stones, open-air rocks, and in shelters shows they are widespread. Finding shelters with *both* paintings and cup marks is new for the region, highlighting cavities as places for complex rituals. People have suggested cup marks were for water rituals, but in Atlantic Europe, they’re also seen as marking symbolic places linked to the earth or spirits, or serving as territorial markers. The similarities in rock art across Atlantic Europe and now including northwest Africa suggest a shared cultural network, maybe conveying knowledge or messages.

What’s really interesting is the spatial relationship between some rock art sites and cemeteries. Idol’s Cave is near burials. The Achakar plateau above it was a burial ground. Ziaten cup marks overlook a plain with many cist and tumuli cemeteries. Several of our newly found rock art sites are within sight of the new cemeteries we found, clustered around that important crossroads. This suggests a deliberate connection between these ritual spaces and burial grounds, perhaps acting as territorial markers along key routes. Similar connections are seen in Iberia and the Middle Draa/Tamanart Valley in southern Morocco, reinforcing the idea of a symbolic link between rock art and burial sites.

Putting the Pieces Together

So, what does all this tell us? From around 3000 BC, the Tangier Peninsula was increasingly connected to the outside world, and this shows up clearly in its ancient ritual landscape. We see a mix of burial practices – pits, caves, hypogaea, cists, tumuli – with strong parallels in southern Iberia and the Sahara. Our new radiocarbon date for Daroua Zaydan confirms that cist burials were happening here by the Early Bronze Age, around 2100 BC, and they continued for a long time, unlike in southern Iberia where they disappeared later and cremation became common.

The discovery of more cist cemeteries, often along major routes, suggests this tradition was more widespread than we thought. These cemeteries might have served as territorial markers for communities, maybe competing for land as things got busier. Finding paired settlements and cemeteries, like they do across the Strait, is still a big goal for future research here.

Cist cemeteries seem mostly confined to the Tangier Peninsula in northwest Africa and were gradually replaced by tumuli. While many Moroccan tumuli are dated later, the older examples in Iberia and the Sahara, and the fact that some tumuli cover cists, make me think the tumuli tradition here might be older too. They likely became more monumental as society changed, perhaps reflecting the rise of elites.

It’s tough to fully understand the social, economic, and cultural dynamics with the data we have, especially the lack of settlement information. The current picture, with seemingly small sites (except maybe Kach Kouch, which needs more work) and little evidence of big defenses or strong central control, might suggest kin-based communities rather than complex societies like the Early Bronze Age Argaric culture in southern Iberia. Differences in burials might reflect individual achievements rather than inherited wealth or power. Or, maybe the Tangier Peninsula was just a less centralized area, part of a wider network with bigger centers located elsewhere – under modern Tangier, or across the Strait, or further south.

The similarities between Iberian and North African cists raise big questions: were they due to trade, migration, or just similar ideas popping up independently? The finding of mixed local and African ancestry in an individual from a cemetery in southern Spain definitely supports the idea of human movement across the Strait.

The continuity we see in rituals and burial grounds in the first millennium BC is fascinating. Even the Phoenician-style hypogaea on the Achakar plateau seem to have been used by locals or people of mixed background, based on the grave goods and the site’s long history. This suggests external influences weren’t just imposed; they were likely negotiated and adapted by local communities. This challenges older ideas about colonization and acculturation, showing that when the Phoenicians arrived, they met active communities with their own networks and established ways of life, including farming. The interaction was probably a complex mix of resistance, blending, and change.

Beyond burials, the standing stones, rock art, and rituals in caves and rivers point to a much broader ritual landscape that needs more exploration. These elements weren’t isolated; their placement along routes and near cemeteries suggests they were interconnected parts of how these communities marked their territory and interacted with their world.

The new rock art discoveries are particularly exciting, showing that the Rif Mountains are a major, largely unexplored area for prehistoric imagery, with clear links to both southern Morocco and Atlantic Europe.

Finally, I have to stress the urgent need for conservation. The destruction we’ve seen from looting, building, and farming is heartbreaking. Losing these sites means losing irreplaceable pieces of North Africa’s past and our chance to truly understand the complex story of this incredible region.

By sharing what we’ve found and highlighting what we still don’t know, I hope we can encourage more research into this overlooked period and help everyone see the Tangier Peninsula’s crucial role in the ancient Western Mediterranean and Atlantic world. It’s a story that’s far from finished.

Source: Springer