When Stress Shows on Your Skin: Unpacking the Cellular Story of Vitiligo

Hey there! So, let me tell you about something pretty wild that researchers have been digging into. You know how stress can sometimes feel like it’s just… everywhere? Like it gets under your skin? Well, turns out, for some folks, it might literally do just that, contributing to conditions like vitiligo, where patches of skin lose their color.

Vitiligo is this fascinating, sometimes frustrating, skin condition where you get these depigmented spots. It happens because the cells that give your skin and hair color – called melanocytes – decide to check out. And get this, over half of people with vitiligo report that stress seems to play a role, either kicking it off or making it worse. But the big question has always been, *how*? What’s the actual mechanism? What’s going on down there at the cellular level?

That’s where this cool study comes in. Researchers wanted to get a really close look at what happens in the skin and the immune system when stress is a factor. Since studying this in humans is tricky, they used a mouse model. Not just any mouse model, but one designed to mimic chronic mental stress. They called it the Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stimulation (CUMS) model. Sounds intense, right? The idea is to give the mice various mild, unpredictable stressors over time, kind of like the low-level, ongoing stress many of us deal with.

Building a Stressy Mouse Model

Okay, so how do you stress out a mouse to study skin? These researchers got creative (and followed ethical guidelines, of course!). They took C57BL/6 J mice and put them through a 12-week program of “chronic unpredictable mild stimulation.” We’re talking things like:

- Cage swaps (a change of scenery, I guess?)

- Tilting cages

- Wet litter (ugh, nobody likes wet socks, right?)

- Confinement

- Brief cold water dips

- Predator sounds or smells

- Rapid light changes

- Tail suspension (just for a short bit!)

They made sure the stimuli were unpredictable so the mice couldn’t just get used to it. They even checked the mice’s body weight (stress often leads to weight loss in these models) and did behavioral tests. And yep, the CUMS mice showed signs of stress and even depression-like behavior compared to the chill control group.

The big visual outcome? After 12 weeks, about 60% of the stressed mice started showing obvious depigmentation and white hairs, especially on their tails. This looked a lot like the depigmentation seen in human vitiligo and other vitiligo mouse models. They even looked under a special light (Wood’s lamp) and stained the skin to confirm the loss of melanin particles.

Peeking Inside with Single-Cell Tech

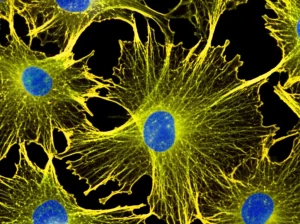

Now, the really exciting part. To figure out the ‘how’, they used this super-powered technique called single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Imagine being able to look at *every single cell* in a piece of skin and see which genes are turned on or off. It’s like getting a detailed report card for thousands of individual cells! They took tail skin samples from the stressed and control mice and ran this analysis.

They ended up with data from over 72,000 cells! When they mapped these cells out based on their gene activity, they could see distinct clusters – basically, different types of cells like keratinocytes (the main skin cells), fibroblasts (connective tissue cells), immune cells, and, crucially, melanocytes.

They noticed something right away: the stressed mice had fewer melanocytes and more immune cells in their skin compared to the control group. This already hints that the immune system might be involved in the melanocyte loss.

The Melanocyte Mystery: Two Fates?

When they zoomed in *just* on the melanocytes, they made a fascinating discovery. Instead of just one big group of melanocytes, the scRNA-seq data revealed three sub-clusters. One cluster looked like keratinocytes that had picked up some melanin (which happens in skin), so they set those aside. But the other two? Those were the real melanocytes, and they looked distinct:

- Mel2: These cells expressed markers for melanocyte stem cells (the ‘parent’ cells that make new melanocytes). They *didn’t* seem to be actively making melanin or dividing much.

- Mel3: These expressed markers for mature melanocytes – the ones busy producing pigment.

In the stressed mice, the number of Mel2 (stem) cells was significantly reduced. And here’s the kicker: these two types of melanocytes seemed to be dying in different ways! The Mel2 stem cells were prone to types of cell death called pyroptosis and necroptosis. The Mel3 mature melanocytes, on the other hand, were more susceptible to oxidative stress, problems with their mitochondria (the cell’s powerhouses), and a specific type of iron-dependent cell death called ferroptosis.

It’s like stress hits these cells differently depending on their maturity! The stem cells seem to get wiped out by inflammatory cell death pathways, while the mature cells succumb to damage from within, like oxidative stress.

The Inflammatory Neighborhood

It’s not just the melanocytes feeling the heat. The researchers also looked at the other cells in the skin’s neighborhood. Keratinocytes and fibroblasts, which make up the bulk of the skin’s structure, also seemed to be involved. In the stressed mice, these cells were pumping out pro-inflammatory signals – things like cytokines and chemokines (chemical messengers that call in immune cells). This creates a “pro-inflammatory micro-environment” right there in the skin, similar to what’s seen in human vitiligo lesions.

Think of it like this: the stress causes the structural cells of the skin to get agitated and start sending out distress signals, which then attracts immune cells and creates a hostile environment for the sensitive melanocytes.

Immune Cells Join the Party (The Wrong Kind!)

Speaking of immune cells, the scRNA-seq showed an increase in immune cells, particularly T cells and macrophages, in the skin of stressed mice. When they looked closer at the T cells, they found an increase in two specific types:

- γδT cells: These are a bit different from the usual T cells. They’re part of the ‘innate’ immune system, meaning they react quickly and non-specifically to threats.

- Th1 cells: These are helper T cells that promote inflammatory responses.

Macrophages (the ‘ Pac-Man’ cells that gobble up debris and pathogens) in the stressed mice were also more inclined towards an ‘M1’ pro-inflammatory state and seemed better at phagocytosis (eating things). Dendritic cells (DCs), which are key players in showing bits of invaders to T cells (antigen presentation), also showed signs of enhanced migration and antigen presentation in the stressed mice.

This suggests that stress doesn’t just affect the melanocytes directly; it also ramps up the local immune system in a way that seems detrimental to pigment cells.

The CXCL16-CXCR6 Connection: A Cellular Handshake?

One of the coolest findings was about how these cells might be talking to each other. Using another analysis tool, they looked at potential communication pathways between different cell types. A key pathway that popped out in the stressed mice was the CXCL16-CXCR6 axis.

Turns out, dendritic cells in the skin of stressed mice had high levels of CXCL16 (a chemokine, a chemical signal). And the γδT cells (those quick-reacting immune cells) had high levels of CXCR6, which is the receptor that binds to CXCL16. It’s like the DCs were waving a flag (CXCL16) saying “Hey! Come over here!” and the γδT cells (with their CXCR6 receptors) were responding to that call.

But the story doesn’t stop in the skin. They also looked at the spleen, a major immune organ. In the spleen of stressed mice, they found an increase in NKT cells (Natural Killer T cells), another type of innate-like immune cell. And guess what? These NKT cells also had elevated levels of CXCR6! Dendritic cells in the spleen were expressing CXCL16 too. This suggests this same communication line might be linking the stressed skin to the wider immune system via the spleen.

The hypothesis is that stress triggers changes in the skin, leading to DCs releasing CXCL16, which recruits CXCR6-positive cells like γδT cells in the skin and potentially NKT cells from the spleen. These recruited immune cells then contribute to the inflammatory environment and damage the melanocytes.

Does This Happen in Humans?

To see if this mouse model was relevant to human vitiligo, the researchers looked at publicly available single-cell data from human vitiligo patients. And they found something similar! In the depigmented skin of vitiligo patients, there was also an increase in T cells, including γδT cells. Interestingly, some CD8+ T cells (often thought to be the main culprits in vitiligo) also showed some characteristics of γδT cells, hinting at this innate-like, rapid response might be more important than previously thought, especially in the early stages.

They also saw evidence of CXCL16 and CXCR6 expression in human vitiligo skin, suggesting this communication pathway might be relevant in people too.

Piecing it All Together

So, what’s the big picture here? This study, using a clever stress model and cutting-edge single-cell technology, gives us a much clearer view of the cellular chaos that might happen in stress-induced vitiligo. It suggests that chronic stress can:

- Create a pro-inflammatory environment in the skin via keratinocytes and fibroblasts.

- Lead to the loss of melanocytes, but maybe in different ways depending on whether they are stem cells or mature cells.

- Activate innate-like immune cells (γδT cells in skin, NKT cells in spleen) potentially via the CXCL16-CXCR6 pathway.

- This non-specific immune response might be a key early event, perhaps even before the more widely studied CD8+ T cell attack kicks in.

It challenges the idea that vitiligo is *just* a simple autoimmune disease mediated by CD8+ T cells specifically targeting melanocytes. It looks more complex, involving stress, inflammation, different types of melanocyte death, and a cast of various immune cells, including those from the innate side.

Why This Matters

Understanding these detailed cellular mechanisms is super important. If we know *how* stress contributes to vitiligo, we might be able to find new ways to prevent or treat it. Targeting the CXCL16-CXCR6 pathway, or finding ways to protect melanocyte stem cells from specific death pathways, could be potential avenues for therapies.

This model, which seems to mimic the human condition quite well (especially the lack of heavy immune infiltration often seen in vitiligo lesions), provides a valuable tool for future research. Of course, it’s just one piece of the puzzle. The study had limitations – it was mainly in male mice, just a snapshot in time, and relied heavily on sequencing data with some validation. More experiments are needed to confirm these pathways and see if blocking them helps.

But still, it’s a big step forward in understanding the intricate dance between our minds, our stress levels, our immune systems, and those precious pigment cells in our skin. It really drives home how connected everything is!

Source: Springer