Spruce’s Secret Weapon: Uncovering the PaChi Gene for Fungal Defense

Hey there! Let’s dive into the fascinating world of trees, specifically a cool type of spruce called Picea asperata. These aren’t just any trees; they’re super important for the environment in places like southwest China. But, like many living things, they face challenges. One big headache for these spruces is a nasty fungal disease called needle cast, caused by Lophodermium piceae. It makes their needles sick, slows them down, and can even be fatal. Not good!

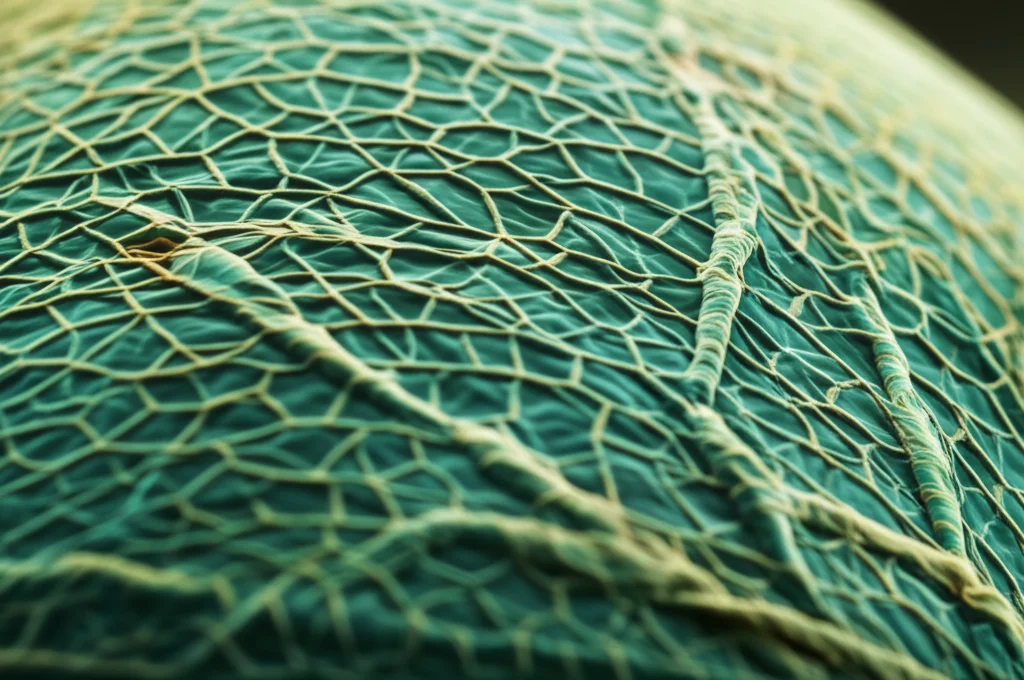

So, what’s a tree to do when faced with a fungal invader? Well, plants have their own defense systems, and one of their secret weapons is a group of proteins called chitinases. Think of chitinases as tiny molecular scissors that are really good at snipping apart chitin. Why is that useful? Because chitin is a major building block of fungal cell walls! Plants don’t have chitin, so breaking it down is a smart way to mess with a fungal attacker.

Finding Our Hero Gene: PaChi

We got really curious about how Picea asperata fights back against this needle cast fungus. We had some previous data that hinted at a specific chitinase gene getting really active when the fungus was around. So, we thought, “Aha! Let’s find this gene and see what it’s all about!”

We successfully isolated this gene from P. asperata and decided to call it PaChi. It’s a pretty neat little package, containing the instructions (an open reading frame) to build a protein made of 255 amino acids.

Getting to Know PaChi: Structure and Family

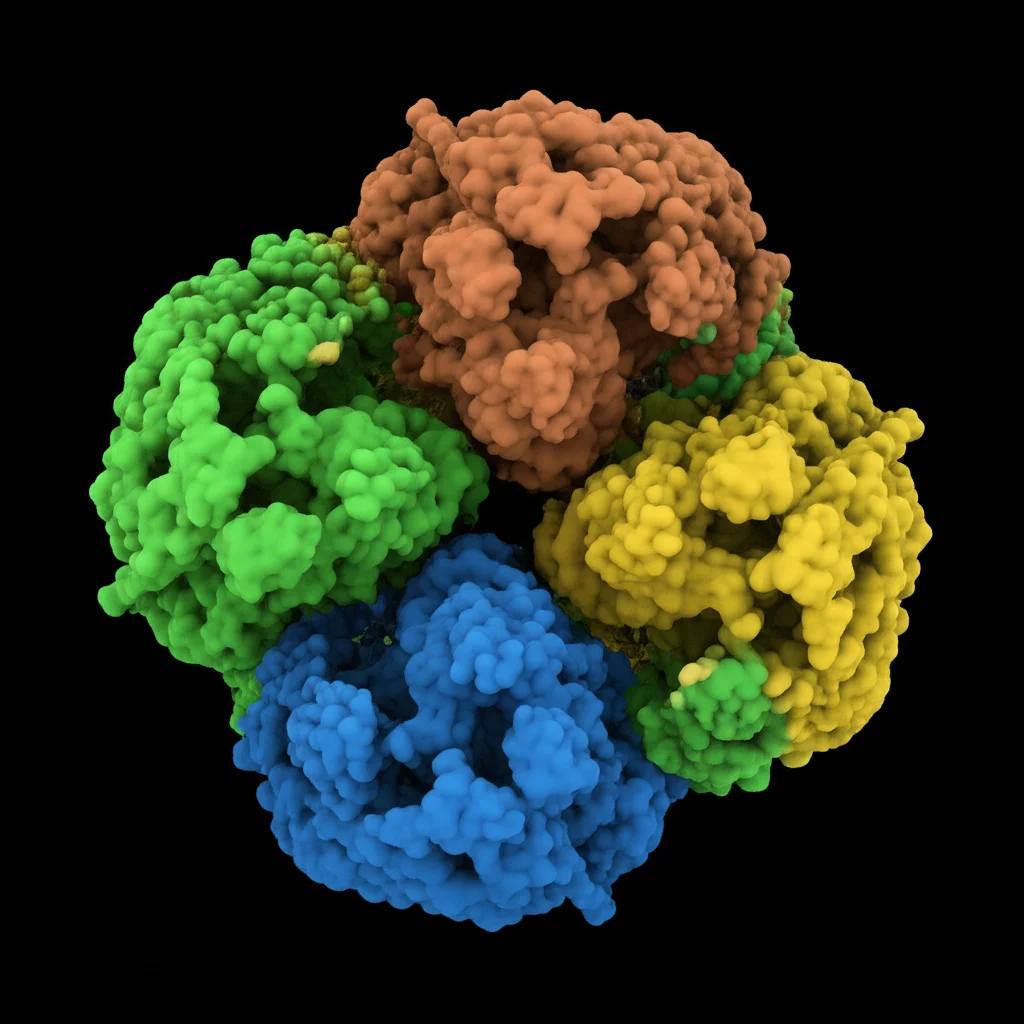

Once we had the PaChi gene, we started poking around to see what kind of protein it makes and where it fits in the big picture of plant defenses. Turns out, PaChi is a member of the GH19 family of enzymes and belongs to Class IV chitinases. These are like specialized units within the plant’s defense force.

Looking at the protein’s predicted structure was pretty cool. It has the classic features you’d expect from a Class IV chitinase:

- A chitin-binding domain: This is like the protein’s “hand” that grabs onto the fungal chitin.

- A catalytic domain: This is the “scissors” part that actually does the cutting.

- Specific active sites within the catalytic domain: These are the precise spots where the chemical reaction happens.

We also compared PaChi to chitinases in other plants, especially its relatives like the Norway spruce. Guess what? PaChi looks incredibly similar structurally and is closely related genetically to the Norway spruce chitinase. This suggests they might have similar jobs!

Where Does PaChi Hang Out?

To understand what PaChi does, we needed to know where in the tree it’s most active. We checked out its expression levels in different tissues:

- Roots

- Phloem (the inner bark)

- Twigs

- Needles

- Young fruits

- Seeds

The results were quite telling! PaChi expression was found in all tissues, but it was highest in the roots and also quite high in the needles. This makes sense! Roots are constantly interacting with soil microbes, some of which are fungi. And needles? They’re the first line of defense against airborne fungal spores like those from L. piceae. The low expression in the phloem suggests it might not be super involved there.

PaChi on High Alert: Responding to Infection

Okay, so PaChi is in the needles, where the fungus attacks. But does it *do* anything when the fungus shows up? This was a big question! We looked at PaChi transcription levels in needles infected with L. piceae over several months.

And the answer is a resounding YES! PaChi expression shot up significantly during the early stages of infection. It peaked around one month after infection, being over 3.5 times higher than in healthy needles. While it decreased a bit after that, it stayed significantly elevated compared to the control. This strongly suggests that PaChi is actively involved in the spruce’s defense response right from the get-go.

Bringing PaChi to the Lab: Making the Protein

Finding the gene and seeing its expression pattern is great, but to really understand what the PaChi protein does, we needed to get our hands on it. So, we used a common lab trick: we put the PaChi gene into E. coli bacteria and got them to churn out the protein for us! We specifically focused on making the mature protein without a little “signal peptide” part, which can sometimes cause issues when making proteins in bacteria.

We successfully produced the recombinant PaChi protein. It showed up on our tests (SDS-PAGE) at about the expected size, around 27 kDa. We figured out the best conditions (like how much of a chemical called IPTG to add and for how long) to get a good amount of the protein. Then, we purified it to get a cleaner sample for testing its capabilities.

What Does This Protein Actually Do? Enzymatic Activity

With purified recombinant PaChi in hand, the next step was to see if it could actually do its job: break down chitin. We used a standard test with colloidal chitin as the target.

Good news! The purified recombinant PaChi definitely had chitinase activity. We measured its specific activity at 4.61 U/mg. We also checked what conditions it likes best to work efficiently. Turns out, it’s happiest at:

- Optimal pH: 7.0 (pretty neutral, like water)

- Optimal Temperature: 40°C (warmer than room temp, but not super hot)

These optimal conditions are similar to some other chitinases out there, though different enzymes have their own preferences.

The Main Event: Fighting the Fungus In Vitro

Okay, the protein breaks down chitin in a test tube. But can it actually affect the *fungus* that causes needle cast, L. piceae? We added our recombinant PaChi protein to dishes where the fungus was growing to see what would happen.

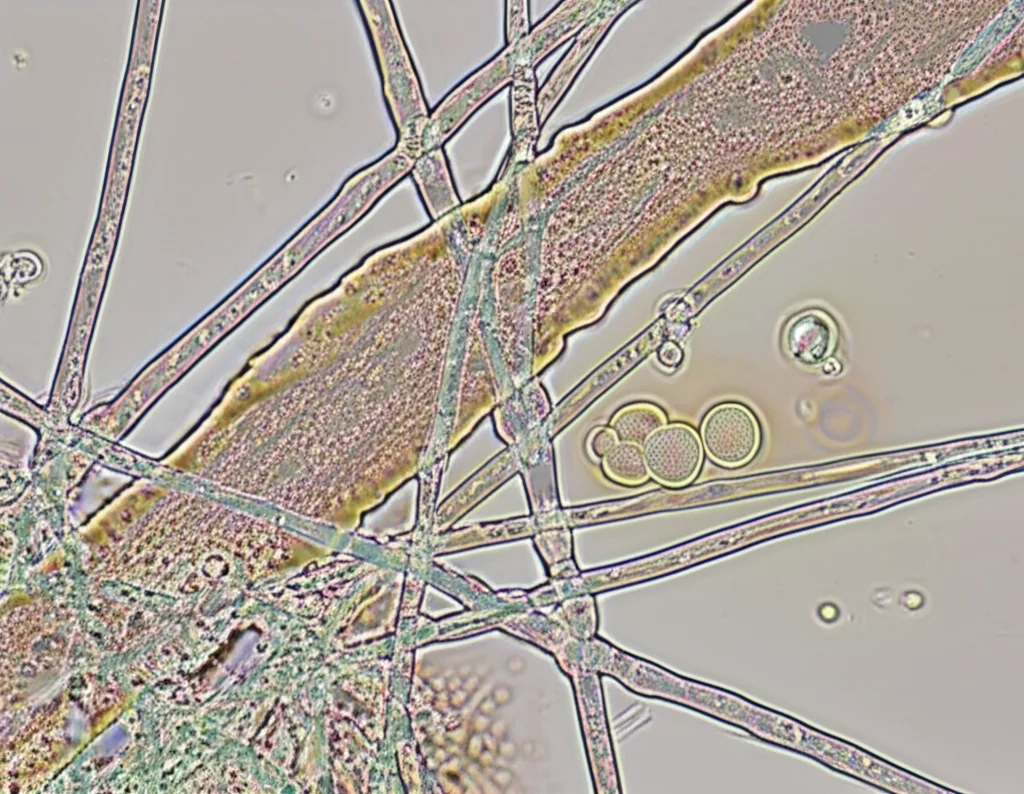

Here’s where it got really interesting. At the concentration and temperature we tested (25°C, simulating the natural environment), the recombinant PaChi didn’t significantly stop the fungus from growing across the dish. You might think, “Hmm, not a great fighter then?” But wait! We looked at the fungal threads (the mycelia) under a microscope after they were treated with PaChi.

Under the microscope, it was a different story! A large number of the fungal mycelia treated with PaChi showed abnormal changes. We saw things like:

- Cell swelling: The fungal cells looked bloated.

- Inclusion body concentration: Stuff inside the cells seemed to clump up.

These changes weren’t seen in the control group that just got water. So, even if it didn’t stop growth completely in this specific test setup, the PaChi protein was definitely messing with the fungus’s structure and internal workings. This is a big deal because healthy mycelia are crucial for the fungus to grow and infect the tree.

So, What Does This All Mean?

This study is pretty exciting because, as far as we know, it’s the first time anyone has identified and characterized a chitinase specifically in Picea asperata. We found that PaChi is indeed a Class IV chitinase with the right tools (binding and catalytic domains) to interact with chitin.

Its high expression in roots suggests it might play a role not just in defense, but potentially in root growth and development too, similar to what’s been seen with chitinases in other plants. But its significant upregulation in needles during L. piceae infection, especially early on, strongly points to its involvement in the tree’s defense against this particular fungal foe.

While our in vitro test didn’t show complete growth inhibition (maybe we need more protein, or test at the enzyme’s optimal temperature of 40°C next time!), the fact that the recombinant PaChi protein caused structural damage to the fungal mycelia is a powerful indicator of its antifungal potential.

These findings lay important groundwork. They tell us that PaChi is a key player in P. asperata‘s response to needle cast disease. This knowledge could be super valuable for future research, maybe looking at how to enhance this defense mechanism or even exploring other chitinase genes in this important tree species. It’s another piece of the puzzle in understanding how trees protect themselves!

Source: Springer