Unpacking the Gooey Secrets: What Soil Microbes Put in Their EPS

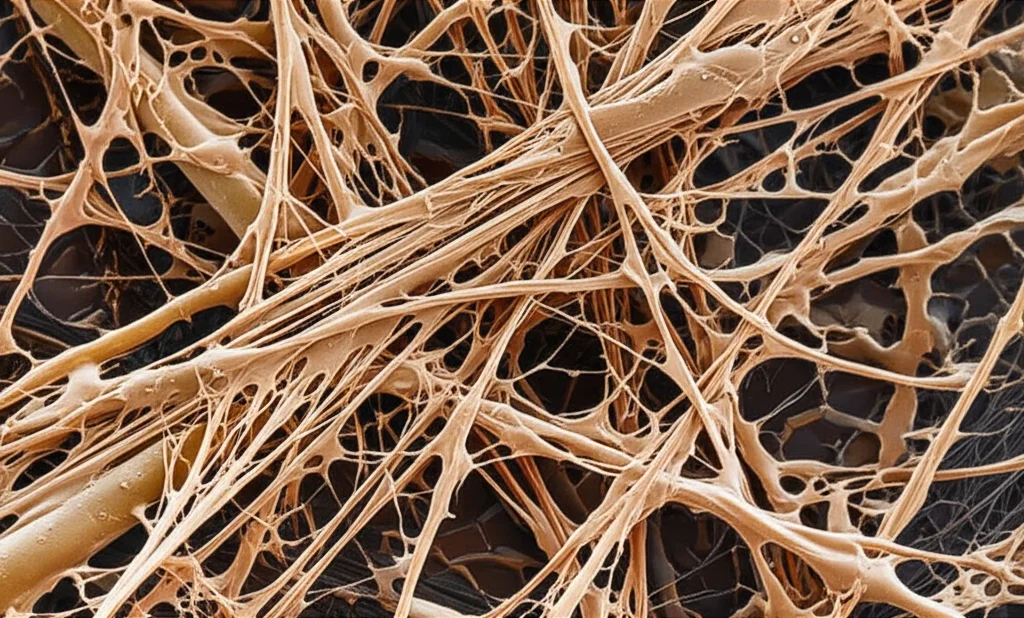

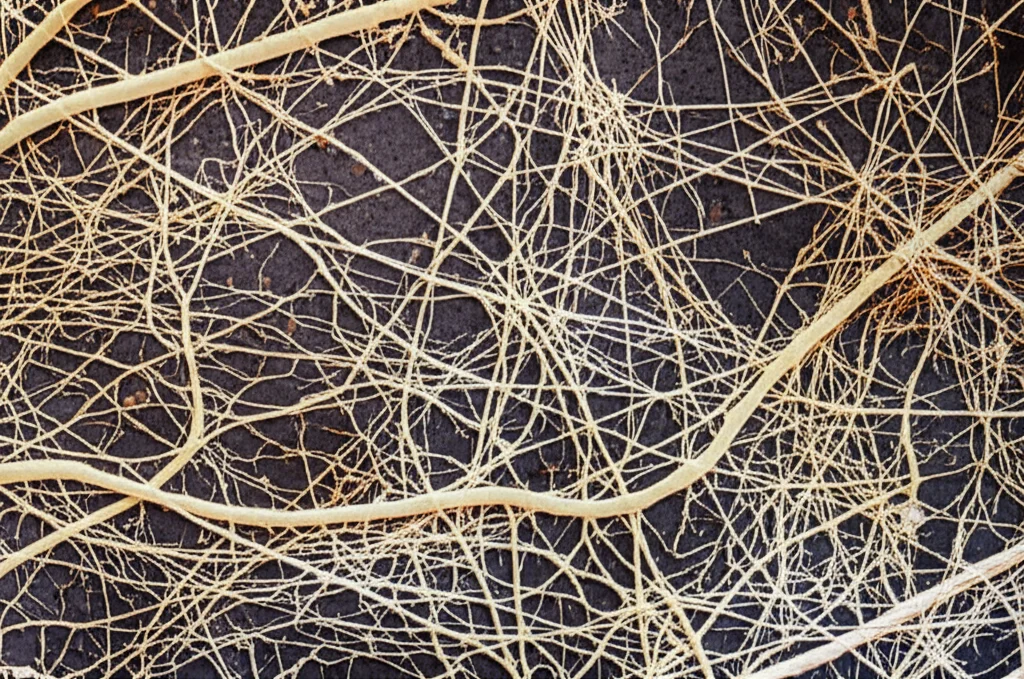

Hey there! Let’s dive into something pretty cool that’s happening right under our feet, in the soil. We’re talking about this amazing stuff called Extracellular Polymeric Substances, or EPS for short. Think of it as the microbial world’s very own construction material – a kind of sticky, gooey matrix that bacteria and fungi build around themselves.

What Are These Gooey Things Anyway?

So, picture this: most tiny critters in the soil, the microbes, don’t just float around willy-nilly. Nope, they often hang out together in communities called biofilms. And what holds these biofilms together, sticking them to surfaces and to each other? You guessed it, EPS! This stuff is super important, not just for the microbes themselves (it helps them grow, stick around, and stay protected), but also for the soil ecosystem as a whole. We’re talking better soil structure, holding onto precious water and nutrients, and even protecting important enzymes that break things down.

Now, we know EPS is a big deal, and we’ve learned a fair bit about it, especially because folks are interested in biofilms for all sorts of things, from cleaning up pollution to understanding infections. But here’s the kicker: figuring out exactly *what* makes up this EPS goo and *how* those different bits work together to do all these cool things, especially in a messy place like soil, has been tricky. Methodological challenges, you know?

We had a hunch that maybe the environment plays a big role. Like, would microbes make more EPS if they had a surface to stick to? And would the type of food they eat (the carbon source) change things? We also knew that while carbohydrates and proteins are usually the main stars of the EPS show, there are other players, like DNA and some interesting molecules called amino sugars, that are hanging out in there too. We specifically wondered about mannosamine (ManN) and galactosamine (GalN), which some recent work suggested might be *only* found in microbial EPS, unlike some other amino sugars.

Setting Up Our Microbial Micro-Worlds

To get a better handle on this, we decided to set up a little experiment. We took ten different types of soil bacteria and ten different types of soil fungi. We grew them in the lab under controlled conditions. We gave them different food – either glycerol, which is like easy-to-eat fast food for microbes, or starch, which is a bit more complex and takes more work to break down. And crucially, we grew them either just in the liquid food medium or with some sterile quartz sand added, giving them a surface to potentially stick to and grow on. We let them chill and grow for four days.

After our four-day microbial party, we carefully extracted the EPS they produced. This extraction method is pretty standard, using something called cation exchange resin (CER). It’s good because it doesn’t mess with the EPS composition too much, but we had a little thought in the back of our minds that maybe it only gets the loosely attached stuff.

What We Found Inside the Goo

Once we had the extracted EPS, we got down to analyzing it. We measured seven different things:

- Total carbohydrates

- Total proteins

- DNA

- Four amino sugars: muramic acid (MurN), mannosamine (ManN), galactosamine (GalN), and glucosamine (GlcN)

We wanted to see how the type of microbe (bacteria vs. fungi), the food source (glycerol vs. starch), and the presence of a surface (with or without quartz) affected both the total amount of EPS produced and *what* was actually in it.

Production vs. Composition: A Tale of Two Drivers

Here’s one of the coolest findings: it turns out that *what* makes up the EPS (its composition) was really strongly influenced by the *type of microbe*. Bacteria and fungi made different kinds of goo. But *how much* EPS they produced seemed to be driven more by the *environment* – the food they ate and whether there was a surface there.

Let’s break it down a bit.

The Main Players: Carbohydrates and Proteins

Proteins in the EPS were higher when microbes were grown on the easy-to-eat glycerol and when they had the quartz surface. Bacteria, on average, produced more EPS protein than fungi across all conditions.

Carbohydrates told a slightly different story. Their production shot up dramatically, especially for both bacteria and fungi, in the treatment with starch *and* quartz. Starch in general led to more carbohydrate production.

This led us to look at the ratio of carbohydrates to proteins (the EPS-carbohydrate/protein ratio). This ratio is thought to be a good indicator of how the biofilm behaves, like how sticky or watery it is. We found this ratio was higher with starch compared to glycerol, and it also increased when the quartz surface was present.

Why does this ratio matter? Well, in water environments, a higher carbohydrate/protein ratio has been linked to biofilms that are less sticky and more water-repellent (hydrophobic). This kind of biofilm might be tougher against things like water, solvents, or even biocides. It could also be better at grabbing onto organic stuff. So, maybe more complex food sources (like starch) or surfaces (like quartz) push microbes to make biofilms that are more hydrophobic, helping them stick and resist harsh conditions.

On the flip side, lower ratios (like with glycerol) might mean more sticky and water-loving (hydrophilic) biofilms. These could be better at holding onto water, which would be super useful for microbes in dry soil. But honestly, we need more experiments to really confirm this link in soil contexts.

The fact that the ratio increased with the quartz surface also hints that carbohydrates might be key players in helping the biofilm stick to solid stuff. Other studies have seen more polysaccharides (a type of carbohydrate) linked to stronger adhesion. So, even though quartz is pretty simple, this finding opens the door to understanding how biofilms stick to more complex soil minerals.

One little note on the carbohydrates: since we used starch as a food source and our extraction method might be gentle, there’s a chance some of the ‘carbohydrates’ we measured included unmetabolized starch, not just the stuff in the EPS structure. But the overall trends we saw still seem valid and give us good clues.

The Mysterious Amino Sugars

Now, let’s talk about the amino sugars – MurN, ManN, GalN, and GlcN. These guys are often used as markers for microbial leftovers (necromass) in soil because they’re part of cell walls. For example, MurN is only found in the cell walls of bacteria (in peptidoglycan). GlcN is in bacterial cell walls and also in fungal cell walls (chitin).

But remember that recent study? It suggested ManN and GalN might *only* come from microbial EPS. Our results added to this puzzle. We found higher concentrations of ManN and GalN in bacterial EPS compared to fungal EPS. Interestingly, the food source or the presence of quartz didn’t seem to change the concentrations of ManN and GalN much within bacteria or fungi. This makes us think maybe these two are tied more to the microbe’s own characteristics or cell wall structure, rather than the immediate environment.

What about MurN and GlcN? We found more MurN in bacterial cultures grown with quartz and glycerol. Since MurN is a bacterial cell wall marker, its presence in the extracted EPS, especially with quartz, might suggest that the quartz caused some physical abrasion during extraction, leading to more dead bacterial cell bits (necromass) being pulled out with the EPS. We saw a similar pattern for GlcN, which also suggests necromass might be part of the extracted extracellular material.

However, here’s where it gets really interesting. In bacterial cell walls, GlcN and MurN should ideally be in a 1:1 ratio. But we found much higher GlcN to MurN ratios in bacterial cultures, especially without quartz. This strongly suggests that a good chunk of the GlcN we measured isn’t just from dead cell walls but is actually a component of the bacterial EPS itself, just like ManN and GalN. This challenges the old idea that GlcN is *only* a necromass marker.

We also looked at the GlcN to GalN ratio, which was generally higher when quartz was present. This could mean different things depending on the microbe, but it adds another layer of complexity to how these amino sugars fit into the EPS picture.

DNA in the Mix

Yep, DNA is also found in EPS! It can come from microbes actively releasing it or from dead cells. We saw that the presence of quartz significantly increased the amount of DNA in the extracted EPS, particularly in bacterial cultures grown on glycerol. This could mean that having a surface encourages more cell turnover (leading to necromass) or that DNA itself plays a role in helping cells stick to surfaces.

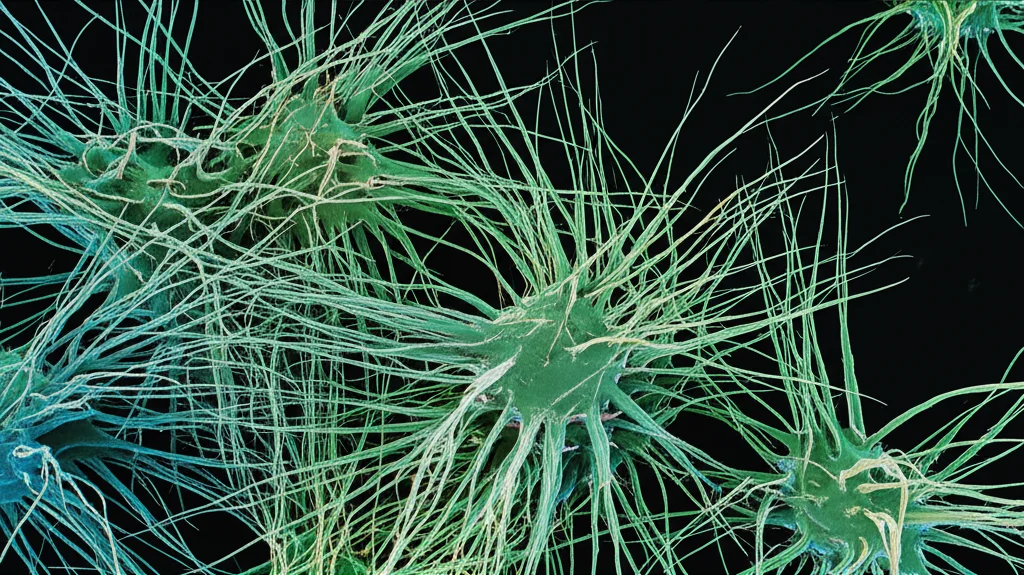

Bacteria generally had much higher concentrations of EPS-DNA than fungi, which makes sense because bacteria tend to have more DNA per cell than fungi. While bacterial EPS-DNA seems important for sticking, fungal EPS-DNA might be more related to how fungi form their biofilms and grow their thread-like structures (hyphae). However, in our short experiment, the fungi probably didn’t have enough time to really get into complex hyphal growth or sporulation, so the fungal EPS-DNA we saw was likely mostly from dead fungal cells.

Microbial Identity Matters (Mostly)

When we crunched all the numbers using something called Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which helps us see the main patterns in complex data, it really highlighted that the biggest differences in EPS composition came down to the *type of microbe*. The amounts of protein, DNA, ManN, GalN, and MurN were key drivers separating bacterial EPS from fungal EPS. This suggests that the specific mix of these components is largely an ‘intrinsic’ characteristic of the microbe itself.

Carbohydrates, however, were the component most affected by the environment (food source and surface). This means that changes in the total *amount* of EPS produced in response to environmental shifts are likely reflected mostly in the carbohydrate fraction.

Interestingly, while bacterial EPS composition seemed more tied to the bacteria’s inherent traits, fungal EPS production and composition showed a stronger response to the environment, particularly the presence of quartz and the type of food (starch). For fungi, increases in EPS weren’t just about carbohydrates but also included GalN and ManN. Why this difference between bacteria and fungi? That’s still a bit of a mystery!

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Our little lab experiment gave us some neat insights into the complex world of microbial EPS. We learned that while the environment (like what food is available and if there’s a surface) mostly dictates *how much* goo is made (especially the carbohydrate part), the type of microbe largely determines *what* kind of goo it is (the mix of proteins, DNA, and amino sugars).

The carbohydrate/protein ratio looks like a promising indicator of how the EPS might function – maybe higher ratios mean more hydrophobic, better-sticking biofilms, though we need more proof. We also confirmed that ManN and GalN are indeed key components of EPS and found strong evidence that a significant amount of GlcN is also part of the EPS matrix, not just from dead cells, especially in bacteria. MurN and DNA often seem to signal bacterial necromass, though DNA might also help with sticking.

This work, using a relatively straightforward extraction method like CER, shows that we can start to pick apart the components of this crucial microbial goo. It opens up exciting possibilities for studying these biofilms in much more complex, real-world settings like actual soil, helping us understand how these tiny structures play such a massive role in soil health and processes. The microbial world is full of sticky secrets, and we’re just starting to unpack them!

Source: Springer