The Chronic Cost: Severe TBI’s Lasting Impact on Brain Blood Flow and Thinking

Alright, let’s talk about something pretty serious that doesn’t get nearly enough airtime: what happens *years* after someone survives a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). You know, the kind of injury that really knocks you off your feet. We often focus on the immediate aftermath, the recovery in the hospital, maybe the first year or two of rehab. But what about a decade down the line? It turns out, for many young survivors, the struggle isn’t over. They often face persistent issues with thinking, memory, and just generally getting their brain to work like it used to. It’s a huge burden, not just for them, but for their families and society too.

Now, our brains are incredibly complex, and they need a constant, well-regulated supply of blood to function properly. Think of it like the delivery service for all the fuel and oxygen your brain cells need to do their job. When this blood flow regulation goes haywire right after a TBI, we know it’s a bad sign for recovery. But what we haven’t really understood is whether these blood flow problems stick around for the long haul, and if they do, whether they’re linked to those chronic thinking difficulties. That’s exactly what we wanted to dig into with this study.

The Lingering Shadow of TBI

Severe TBI is a leading cause of long-term disability, no doubt about it. Survivors often struggle with things like remembering stuff, paying attention, making plans, and processing information quickly. These aren’t just minor annoyances; they can really impact someone’s ability to work, study, and just live a full life. While the initial injury is like the main punch, there are these “secondary” injury mechanisms that kick in afterwards, and mounting evidence suggests *these* are the culprits behind a lot of the long-term issues.

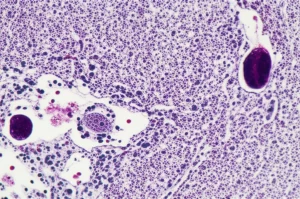

We know that regulating cerebral blood flow (CBF) is absolutely vital for keeping our cognitive engines running smoothly. TBI, especially severe TBI, is notorious for messing with these regulatory mechanisms right from the start. Acutely, problems with CBF autoregulation – the brain’s ability to keep blood flow steady despite changes in blood pressure – are a big predictor of how well someone will recover. It makes sense, right? If your brain isn’t getting a stable blood supply, it’s going to struggle.

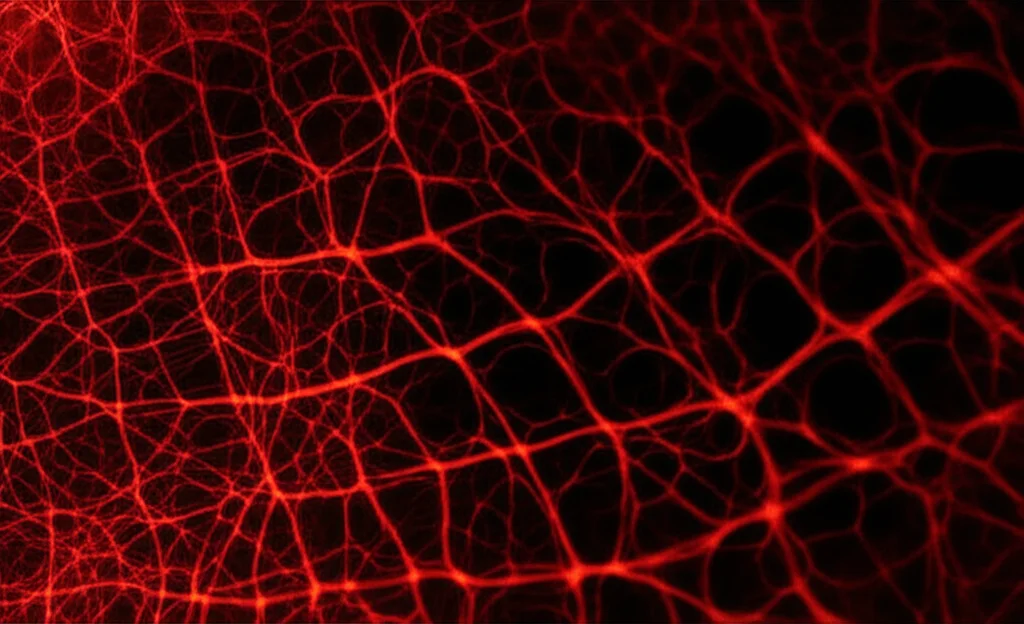

But there’s another crucial mechanism called *neurovascular coupling* (NVC). This is the brain’s brilliant way of directing blood flow precisely to the areas that are working hardest at any given moment. When you’re thinking, learning, or remembering, certain parts of your brain light up with activity, and NVC ensures those areas get an extra boost of blood flow to meet their increased demand. It’s like a smart, on-demand delivery system. Studies have shown that when NVC is impaired in various conditions, it can contribute to cognitive problems. Our own previous work in mice even showed that messing with this specific NVC response was linked to decreased cognitive function.

There’s also been talk about the role of growth factors, specifically something called IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1). IGF-1 is important for the health of the tiny blood vessels in the brain, and low levels have been linked to impaired NVC and CBF regulation. Since TBI can sometimes mess with the system that produces IGF-1, leading to deficiency in a significant number of survivors, it seemed plausible that chronic low IGF-1 could be contributing to long-term vascular and cognitive issues.

So, putting it all together, we had a couple of big questions we wanted to answer:

- Does severe TBI lead to *chronic* problems with NVC and CBF autoregulation, and are these problems linked to cognitive deficits years later?

- Does TBI-induced IGF-1 deficiency play a role in these long-term vascular impairments?

To tackle this, we brought in some young folks who had survived severe TBI a good chunk of time ago and compared them to healthy people their age. We used a bunch of different tools to look at their brain function and blood flow.

Peeking Inside the Brain’s Plumbing

Our study involved 33 survivors of severe TBI, who were, on average, about 37 years old and roughly 10 years out from their injury. We also had 21 healthy volunteers who were around the same age. We invited them to spend a day with us, where we put them through a battery of tests.

First up, we did a deep dive into their cognitive function. We used a whole suite of neuropsychological tests to check out their memory (visual and verbal), executive function (things like planning, flexible thinking, and impulse control), attention, and language skills. We wanted to get a really detailed picture of how their thinking abilities were holding up.

Then, we looked at their brain’s blood flow. We used MRI to measure their *basal* CBF – basically, how much blood is flowing when they’re just resting. We also used transcranial Doppler (TCD) to assess CBF autoregulation and, crucially, *functional* TCD (fTCD) to measure neurovascular coupling. For the NVC part, we had them do some cognitive tasks while we monitored their blood flow response in the middle cerebral arteries (major vessels supplying the brain). We specifically looked at how much the blood flow *changed* when their brain was actively engaged in these tasks.

Finally, we took blood samples to measure their levels of IGF-1 and a related protein, IGFBP-3, to see if that growth factor system was out of whack.

So, what did we find?

Well, confirming what we already suspected, the TBI survivors definitely showed significant impairments across the board in memory (visual, auditory verbal, short-term, and working memory) and executive function compared to the healthy controls. No big surprise there, but it reinforced that these cognitive issues are indeed a chronic reality for this group.

Here’s where it gets really interesting. When we looked at their *basal* CBF using MRI and their CBF *autoregulation* using TCD, we didn’t find any significant differences between the TBI group and the controls. It seems like, years after the injury, the brain’s basic blood flow and its ability to maintain steady flow *at rest* had largely normalized. That’s good news, right?

But then we looked at the *neurovascular coupling* responses during the cognitive tests. And bam! The TBI survivors had significantly *impaired* NVC responses. Their brains weren’t able to ramp up blood flow as effectively to the areas working on the tasks compared to the healthy folks. This impairment was still present a decade after the injury.

And here’s the kicker: this impaired NVC was significantly *correlated* with their cognitive performance. The weaker their NVC response, the worse they tended to score on the memory and executive function tests. This suggests a direct link between this specific blood flow problem and their difficulties with thinking.

What about the IGF-1 hypothesis? Turns out, we didn’t find any significant differences in IGF-1 or IGFBP-3 levels between the TBI survivors and the controls. And their IGF-1 levels weren’t associated with their NVC impairment or their cognitive function in this chronic phase. So, while IGF-1 might play a role right after the injury, it doesn’t seem to be the primary driver of the *chronic* NVC problems we observed.

What Does It All Mean?

Our findings paint a pretty clear picture: severe TBI leaves a lasting mark on the brain’s ability to regulate blood flow *in response to activity*. While the basic delivery system might recover (basal CBF and autoregulation), the “smart, on-demand” part (NVC) remains broken years later. This chronic NVC impairment, we believe, is a major reason why young TBI survivors continue to struggle with cognitive tasks. When their brains are working hard, the active regions might not be getting enough blood, and therefore not enough oxygen and nutrients, to perform optimally.

It’s fascinating, and a bit concerning, that this NVC impairment seems to persist even a decade out. We did find a correlation between better NVC and more time since the injury, and also with a higher initial GCS score (meaning a less severe initial injury), which hints that there might be some slow, ongoing recovery, but it’s clearly not complete for everyone.

This persistent vascular dysfunction is particularly noteworthy because impaired NVC is also a known player in other brain conditions associated with cognitive decline, like Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. This raises a serious question: could this chronic NVC problem after TBI put survivors at a higher risk for developing these neurodegenerative conditions later in life? It’s a possibility that definitely needs more investigation.

Since IGF-1 didn’t seem to be the culprit in this chronic phase, we need to look elsewhere for the underlying mechanisms driving this long-term NVC impairment. Maybe it’s chronic inflammation, ongoing oxidative stress, problems with the brain’s energy factories (mitochondria), or damage to the blood-brain barrier. Pinpointing these mechanisms is crucial because they could become targets for new treatments.

So, what are the big takeaways and where do we go from here?

First, our study really highlights that chronic NVC impairment is a significant, measurable problem in young severe TBI survivors, and it’s directly linked to their cognitive difficulties. This means we need therapies that specifically target this vascular dysfunction. Could things like specialized vascular rehabilitation programs, certain medications (maybe antioxidants?), or brain stimulation techniques help restore NVC and improve thinking skills? It’s a promising avenue for research and clinical trials.

Second, our study was a snapshot in time (cross-sectional). We need *longitudinal* studies that follow survivors over many years to see how NVC and cognitive function change over time. Does the impairment get worse, stay the same, or is there some very slow recovery happening? Understanding these patterns will help us figure out *when* interventions might be most effective.

Finally, the potential link between chronic TBI-induced vascular dysfunction and an increased risk of later-life neurodegenerative diseases is a major concern. Future research should explore this connection further and investigate whether improving NVC after TBI could actually help protect against future cognitive decline and dementia.

In a nutshell, our work provides strong evidence that the brain’s ability to match blood flow to its needs remains impaired for years after severe TBI, and this is a key factor contributing to long-term cognitive problems. While basal blood flow and autoregulation seem to bounce back, the NVC system doesn’t. This emphasizes the urgent need to understand the “why” behind this chronic dysfunction and to develop ways to fix it. By focusing on restoring neurovascular health, we might just be able to significantly improve the long-term outcomes and quality of life for young TBI survivors. It’s a challenging puzzle, but one that’s absolutely worth solving.

Source: Springer