Conil’s Buried Secret: How the 1755 Tsunami Wrote Its Story in the Sand!

Hey everyone! Ever wondered how a catastrophic event from centuries ago can leave its fingerprints right under our feet, even in a bustling town? Well, buckle up, because I’m about to take you on a fascinating journey to Conil de la Frontera, a beautiful spot on the southern coast of Spain. We’re diving deep – literally – into the aftermath of the infamous 1755 Lisbon earthquake and the monster tsunami it unleashed. It’s a story written in sand, shells, and believe it or not, ancient tuna bones!

A Town with a Tale: Conil and La Chanca

Our main stage for this historical detective story is a place called “La Chanca” in Conil. Picture this: Conil de la Frontera is nestled southeast of the Gulf of Cádiz, kissed by the Atlantic waves. The town itself sits on a little rise, while to the east, you’ve got the stunning Castilnovo beach and dune complex. Right in the heart of the old town is La Chanca. Back in the 16th century, it started as a small fortress, but its real claim to fame was becoming a hub for the tuna salting industry (known as ‘almadraba’). This was big business, a cornerstone of the local economy for the Duchy of Medina Sidonia, who pretty much had a monopoly on tuna fishing along the whole Andalusian coast from the 15th century!

Initially, all this salty business happened right out on the beach. We even have historical documents and a cool engraving by Hoefnagel from 1572 showing this. But, as you can imagine, being out in the open wasn’t always safe. Continuous attacks (think pirates and raiders!) pushed the Duke of Medina Sidonia to order the construction of a proper fortification. This was La Chanca – built to protect not just the precious tuna production but also the warehouses storing fishing gear and all the bits and bobs for the salting activity. Little did they know, a far more terrifying force of nature was heading their way.

The Day the Wave Hit

On November 1, 1755, disaster struck. A violent earthquake off the coast of Lisbon, Portugal, triggered one of Europe’s most devastating tsunamis. And La Chanca? It was right in the firing line. Historical sources, including a report by the Royal Academy of History for King Ferdinand VI, tell us that the fortress was completely devastated. It took the direct impact of the first wave, which was likely the most destructive. Imagine the scene – a wall of water, estimated by historical documents to be between 8 to 10 meters high, crashing into this small fishing town.

Fast forward to 2010. During archaeological excavations at La Chanca, something peculiar caught the eye of the archaeologists. About 50-60 cm deep, they found a distinct layer of sediment. This wasn’t just any dirt; it was a jumbled mix of 18th-century materials: fragments of tuna (of course!), livestock remains, bits of tableware, pots, everyday utensils, all mixed up with debris from the collapsed building itself. It was like a snapshot of the chaos from that fateful day. Other researchers had looked into sediments at La Chanca before, even finding materials from older high-energy events that got stirred up by the 1755 catastrophe. This new study, though, aimed to dig even deeper into what these sediments could tell us.

Unearthing the Evidence: What the Sediments Say

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake-tsunami didn’t just damage buildings; it tragically claimed human lives and caused massive destruction in Conil. The nearby Castilnovo neighbourhood, right on the beach, was completely wiped out. So, a key goal of this research, beyond just understanding the La Chanca sediments, was to try and estimate how high that terrifying tsunami wave actually was. This isn’t just about looking back; it’s crucial for understanding what could happen if such an event repeated itself.

To piece this puzzle together, researchers got to work. They scoured historical sources, including previously unreviewed documents from the General Archive of the Duchy of Medina Sidonia Foundation. They analyzed old maps from before and after the disaster. And, of course, there was the hands-on sediment study. Samples were taken from various spots for comparison:

- The beach

- Current dunes

- The Salado River channel

- A known tsunami fan in the floodplain

- And, crucially, from the archaeological site at La Chanca.

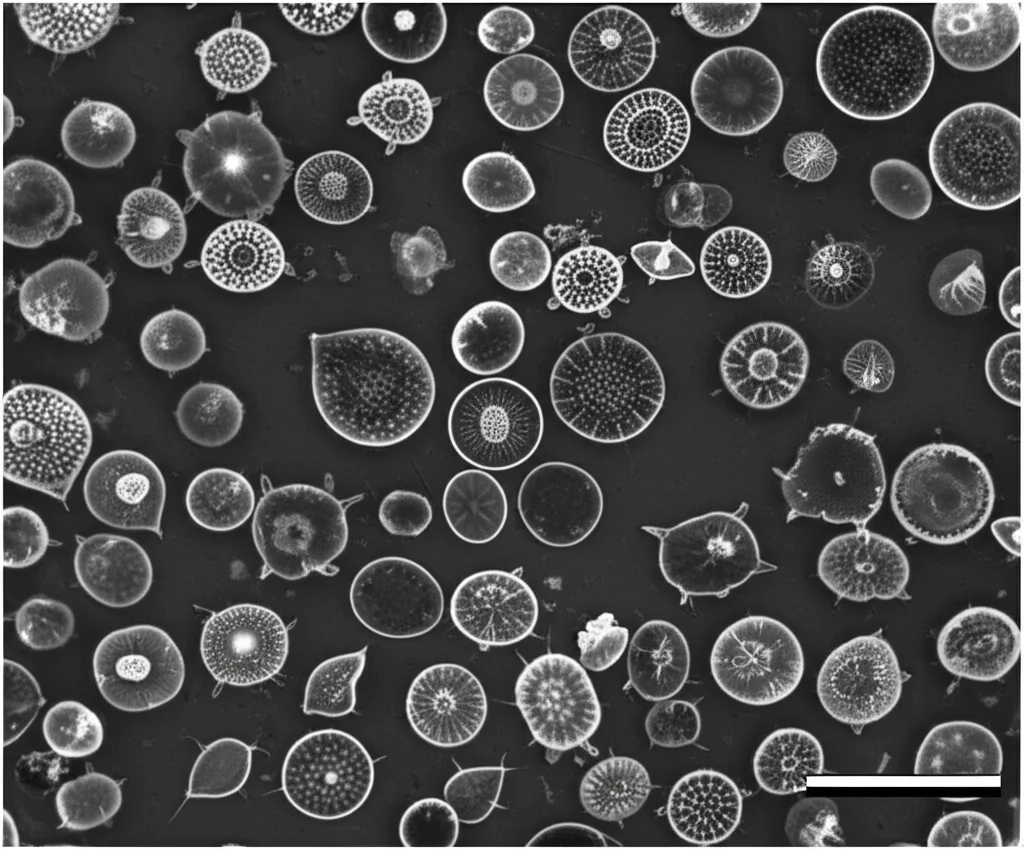

These samples went through granulometric (grain size) and morphoscopic (grain shape) analyses. Scientists also identified tiny foraminifera (marine microorganisms) and other bioclasts (fragments of shells or skeletons) within the deposits. Interestingly, they didn’t need Carbon-14 dating because the sediments were found in such a well-documented historical and archaeological context – literally sealed by the debris of the fortress destroyed in 1755 until they were uncovered in 2010!

Marine Invaders: Clues from the Deep

So, what did these tiny clues reveal? The sediments from inside La Chanca are overwhelmingly marine in origin. They’re packed with tuna scales and spines (no surprise there, given its history!), and about 50% of the material is made up of bioclasts, even if many are too fragmented to identify precisely. But among the identifiable bits were bryozoans (colonial marine animals) and both planktonic (free-floating) and benthic (sea-floor dwelling) foraminifera. Specifically, they found Globigerina (planktonic) and Cibicidoides pseudoungerianus (benthic), a type that lives anywhere from 5 to 5,000 meters deep on the seafloor! These little guys are like tiny messengers from the ocean, confirming the marine source of the La Chanca deposit.

The evidence pointing to the 1755 tsunami is pretty compelling:

- Marine Life: The presence of these deep-sea and coastal marine organisms is a dead giveaway.

- Transported Tuna: The tuna remains found inside La Chanca weren’t just any scraps. Bone studies showed they came from massive specimens, up to 14 years old and weighing over 300 kg! These were likely fish caught earlier and stored outside the fortress. Something with enormous force must have picked them up and dumped them inside. A tsunami fits the bill perfectly.

- Swept-Away Livestock: Inside some of the fortress’s brine ponds, they found remains of livestock. Historical documents confirm that animals were swept away and killed by the tsunami. This tells us the wave packed a serious punch.

Even the sand itself tells a story. The La Chanca sediments have a high percentage of rounded quartz, very similar to the sands on the current beach and dunes just a few hundred meters away. The grain size (medium sands, around 0.32 mm) and other technical characteristics (leptokurtic curves, high Trask index) are also very much like other known tsunami deposits. This is quite different from the finer sands found in the nearby river and dune systems, making it clear that the urban area’s deposit came from the wave scouring the beach and dunes.

The Wave’s Fury and Today’s Risks

Historical records paint a grim picture: Conil de la Frontera was one of the hardest-hit towns. Twenty-four lives were lost, nearly 600 head of livestock perished, and numerous buildings in the historic centre were obliterated. The small village by the Castilnovo Tower was completely flattened.

So, how high was that wave? Most sources agree it reached about 8 to 10 meters above mean sea level. This makes sense because the La Chanca building itself is about 5 meters above sea level, and its walls were over 4 meters high. The wave clearly overtopped it. It even reached buildings like the Guzmán Tower, the Church of Santa Catalina, and the prison, which are perched on a hill about 10-11 meters above sea level! GIS analysis, combined with historical documents, suggests the wave came from a west-southwest direction, travelling over 120 meters inland with a gradient of over 5%, smashing through obstacles.

Interestingly, the earthquake itself seems to have caused minimal damage in Conil – just a bit to the church tower. The real catastrophe was the tsunami. Now, here’s the sobering part. Using these findings, researchers mapped out the area that would be impacted by a similar 8-meter tsunami today. With modern coastal urbanization and the tourism boom, a much wider region would be affected. In the study area alone (about 1 km²), around 245 people live, and there are 350 homes and other bits of infrastructure. The effects could be far worse than in 1755, especially given the lack of widespread warning systems and specific protection plans for such an event. The sheer number of structures close to the coast highlights a pretty significant hazard.

Lessons from the Past, Warnings for the Future

This study is a fantastic piece of detective work! It conclusively confirms that the sediment found in the heart of Conil, about 5 meters above sea level, is indeed a deposit from the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and tsunami. The clues – foraminifera, massive tuna remains, beach and dune sand, even cattle bones matching historical accounts – all point to this one, devastating event.

It’s highly probable that the tsunami wave towered 8 to 10 meters high, crashing into the town with incredible force. And the really crucial takeaway? Estimating the number of people and buildings at risk today if such a disaster were to repeat. Conil now has over 23,000 residents. The consequences could be incredibly serious. Investigations like these into past disasters aren’t just academic; they’re vital for helping us prepare for, and hopefully prevent, future ones. For Conil de la Frontera, the risk is clear. The scary thing is, this kind of event could happen again, and without the old fortress walls (which are no longer there to offer any protection), the impact could be even more devastating than it was nearly 270 years ago. Food for thought, isn’t it?

Source: Springer