Sandy Soil’s Thirsty Problem? This New Gel Might Be the Answer!

The Challenge: Thirsty Sand

Alright, let’s talk about sandy soil. If you’ve ever tried to grow anything in it, you know the struggle is real. Water just zips right through! It’s like trying to fill a sieve. This is a massive headache, especially when we’re facing global water shortages. Agriculture uses a ton of water, and losing so much of it to deep percolation and evaporation in sandy areas is just… well, wasteful. We need smarter ways to manage water in these soils.

Enter the Superabsorbent Hero

So, what’s the deal? Scientists are looking at clever materials called superabsorbent hydrogels (SAHs). Think of them like tiny sponges that can soak up water hundreds, even thousands, of times their own weight and then hold onto it. Pretty neat, huh? When you mix these into sandy soil, they can dramatically improve its ability to hold moisture, meaning you don’t have to water as often, and less water gets lost.

There are lots of different SAHs out there, but the ones made from natural stuff like cellulose are getting a lot of attention because they’re more eco-friendly and cheaper. Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) is one such natural base. It’s got these hydrophilic groups (basically, bits that love water) that make it good at absorbing moisture. But, on its own, CMC isn’t the toughest or the best at soaking up *massive* amounts of water quickly.

Building a Better Sponge

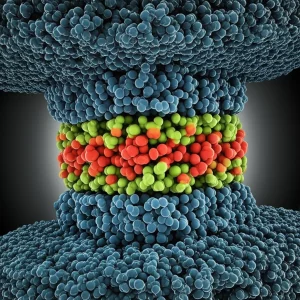

This is where the clever part comes in. To make CMC even better, you can “graft” other polymers onto it. Imagine the CMC as the trunk of a tree, and you’re attaching new, super-absorbent branches to it. In this study, they grafted a mix of two synthetic monomers, acrylamide (AM) and 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonic acid (AMPS), onto the CMC backbone. AM forms polyacrylamide (PAM), a common soil conditioner, and AMPS forms poly(AMPS), which is great because it has sulfonic acid groups that are super hydrophilic and also handle salts well (important for different water types).

The goal was to create a new hydrogel, CMC-g-(PAM-co-PAMPS) SAH, that’s not only great at holding water but also does it *fast* and can handle real-world conditions.

Checking Under the Hood

How do you know if you’ve actually made this new material? Scientists have some cool tools for that. They used:

- FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy): This is like taking a chemical fingerprint. It showed new peaks in the spectrum of the grafted material compared to pure CMC, confirming that the PAM and PAMPS bits successfully attached.

- XRD (X-ray Diffractometer): This looks at the internal structure. Pure CMC has a bit of a crystalline structure, but after grafting, it became more amorphous (less ordered). This is actually *good* for water uptake because it gives water molecules more space to wiggle into.

- TGA (Thermogravimetric Analysis): This tests how well it handles heat. The grafted hydrogel showed improved thermal stability, meaning it can withstand higher temperatures before breaking down compared to the original CMC. It lost half its weight at 391°C, versus 331°C for pure CMC. That extra stability is a plus!

- SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy): This gives you a close-up look at the surface. Pure CMC looked granular, but the grafted hydrogel had a rough, wrinkled, and undulating surface. This increased surface roughness can help with water absorption.

Finding the Sweet Spot: Optimizing the Recipe

Making the perfect hydrogel isn’t just about mixing stuff together; it’s about getting the recipe and the “cooking” conditions just right. They played around with different factors to see what gave the best results:

- CMC Concentration: Too much CMC made the mixture too thick, which actually *reduced* the amount of PAM/PAMPS that could be grafted on (% add-on). Lower CMC concentrations worked better for grafting.

- Total Monomer Amount (AM + AMPS): Increasing the total amount of AM and AMPS monomers generally increased the % add-on (more stuff grafted). However, paradoxically, the *highest* water uptake was seen with a *lower* total monomer amount (3% gave 118 g/g WU vs. 18% giving 87 g/g WU). This is because too many monomers can make the resulting gel network too dense, making it harder for water to get in.

- AM:AMPS Ratio: The ratio of the two monomers mattered. More AM (like a 2.5:0.5 ratio) led to higher % add-on and better water uptake (118 g/g). Why? AM is more reactive in this process, and while AMPS is super hydrophilic, too much of it can interfere with the grafting process and even hinder hydrogen bonding with water molecules.

- Crosslinker (MBA) Amount: A crosslinker is like the glue that holds the 3D network together. Increasing the crosslinker amount increased the % add-on (made the network denser), but it *decreased* water uptake. The sample with the lowest % add-on (from less crosslinker) actually soaked up the most water (183 g/g). You need enough crosslinking to form a stable network, but not so much that it becomes too rigid to swell.

- Initiator (APS) Concentration: The initiator kicks off the grafting reaction. Too much initiator can cause the reaction to finish too quickly, resulting in shorter grafted chains and lower % add-on and water uptake. A lower initiator concentration (0.05%) gave the best water uptake (306 g/g).

- Grafting Time e Temperature: There’s a sweet spot for how long and how hot you “cook” it. Grafting time increased % add-on and water uptake up to 2 hours, then plateaued. Temperature was optimal around 70°C; too hot (80°C) started to hinder the process.

Based on all this testing, they figured out the optimal conditions to get the best performance from their hydrogel.

How Well Does This Sponge Work?

Okay, so they made the gel. How good is it at its job – soaking up water?

- Speed: This is a big one. The hydrogel soaked up water *really* fast. It reached its maximum uptake capacity within just 15 minutes! And the maximum was impressive: 313 g/g. That’s over 300 times its weight in water, and it did it in a flash.

- Environmental Conditions:

- pH: It loved higher pH levels (6-8), where it soaked up the most water (289-313 g/g). In acidic conditions (pH 3-4), the water uptake was much lower (66-98 g/g). This is because the acidic environment messes with the charged groups in the gel that help it swell.

- Temperature: Warmer water (up to 40°C) actually increased water uptake (up to 319 g/g), likely because it made the gel network more flexible. But too hot (50°C) caused the uptake to drop, possibly damaging the gel structure.

- Particle Size: The size of the little gel bits matters. Medium-sized particles (250-500 µm) were the best, hitting that 313 g/g uptake. Smaller particles (125-250 µm) tended to clump together, reducing their surface area and uptake (215 g/g). Larger particles also had lower uptake.

- Salts (TDS): This is crucial for real-world use. The gel soaked up *much less* water in tap water (375 ppm TDS) compared to distilled water (1.2 ppm TDS). Dissolved salts reduce the osmotic pressure difference that helps the gel swell. This is a common challenge for SAHs, but the AMPS component helps give it some salt resistance compared to gels without it.

- Reusability: Can you dry it out and use it again? Yes! They tested it over five cycles of soaking and drying. After five cycles, it still had over 70% of its original water uptake efficiency (around 220 g/g). This means it has decent mechanical stability and can be reused, which is important for practical applications. The slight loss in efficiency could be due to some fatigue in the network or changes in structure over cycles.

Putting the Gel in the Sand: The Real Test

The ultimate goal is to help sandy soil hold water. They set up an experiment with cylinders filled with sandy soil – one with pure sand (the control) and one with sand mixed with their new hydrogel. They poured water in and measured how much drained out and how fast.

The results were pretty clear:

- Reduced Water Outflow: A lot less water drained out of the cylinder containing the sand-hydrogel mix compared to the pure sand.

- Slower Flow Rate: The speed at which water moved through the sand was significantly reduced. In pure sand, the flow rate was 0.96 cm/min (for a 10cm layer) and 0.61 cm/min (for a 20cm layer). With the hydrogel added, these rates dropped dramatically to 0.32 cm/min and 0.15 cm/min, respectively. That’s a huge difference!

Why does the gel do this? It quickly absorbs water and swells up, taking up space between the sand particles. This reduces the size and connectivity of the pores water flows through, basically creating roadblocks that slow the water down and allow the soil to hold onto it longer. The effect was even more pronounced with a deeper layer of sand, likely due to factors like increased compaction and longer flow paths.

The Takeaway: A Promising Solution

So, what’s the big picture here? This new CMC-g-(PAM-co-PAMPS) superabsorbent hydrogel looks really promising for tackling the problem of poor water retention in sandy soils. It’s made using a natural base (CMC), it has a structure that helps it soak up water fast, it’s more heat stable than the original material, and crucially, it can absorb a massive amount of water very quickly (313 g/g in 15 minutes!).

When mixed into sandy soil, it does exactly what we need it to do: it drastically reduces water loss by slowing down how fast water drains through. This means less water is needed for irrigation, which is a win for farmers, the environment, and everyone facing water scarcity.

What’s Next? The Road Ahead

Of course, no new technology is without its challenges. For this hydrogel to be widely adopted, they need to look at things like:

- How well does it break down in different soil types and environments? Biodegradability is key for long-term sustainability.

- Are there any environmental sensitivities or long-term impacts?

- How much does it cost to produce on a large scale?

Future research will also explore if this hydrogel can be used to hold and slowly release fertilizers, which would be another huge benefit for plant growth in poor soils. And, of course, they need to test it out in real fields, not just in the lab, to see how it performs under actual farming conditions.

But all in all, this study presents a really solid step forward in developing effective soil conditioners for sandy areas. It’s exciting to see how materials science can offer practical solutions to real-world problems like saving water in agriculture!

Source: Springer