Unmasking the Silent Link: Undernutrition and Asymptomatic Malaria in Rwanda’s Little Ones

Let me tell you about something really important happening in global health, specifically for the youngest among us in places like Rwanda. We often hear about malaria and malnutrition as big, scary problems, and they absolutely are, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. They hit kids under five years old particularly hard, contributing significantly to illness and even death. These aren’t just health issues; they’re tied into bigger goals like ending poverty, achieving zero hunger, and ensuring good health for everyone.

Rwanda has actually made some fantastic strides in tackling both malaria and undernutrition over the past couple of decades. They’ve seen a real drop in malaria cases and a decrease in childhood stunting. This is thanks to some serious effort – better healthcare, getting bed nets and house spraying out there, and involving communities. It’s genuinely impressive progress!

But here’s the twist, and what this study really dives into: there’s a sneaky side to malaria called asymptomatic malaria. These are cases where kids are infected with the parasite but don’t show any symptoms. They aren’t visibly sick, so they don’t get tested or treated. This makes them silent carriers, keeping the transmission cycle going. And we suspected there might be a link between these hidden infections and a child’s nutritional status. That’s where our study comes in.

The Study’s Mission: Peeking Behind the Symptoms

What we really wanted to figure out was the relationship between a child’s nutritional health – things like being stunted (too short for their age), wasted (too thin for their height), or underweight (too thin for their age) – and having one of these asymptomatic malaria infections in Rwanda. While we know malaria can make kids malnourished, and malnutrition can make kids more vulnerable to getting sick, the specific connection with *asymptomatic* malaria in this particular setting wasn’t super clear. So, our goal was to explore this potential link and see if undernutrition indices were associated with these hidden malaria cases.

How We Looked at the Data

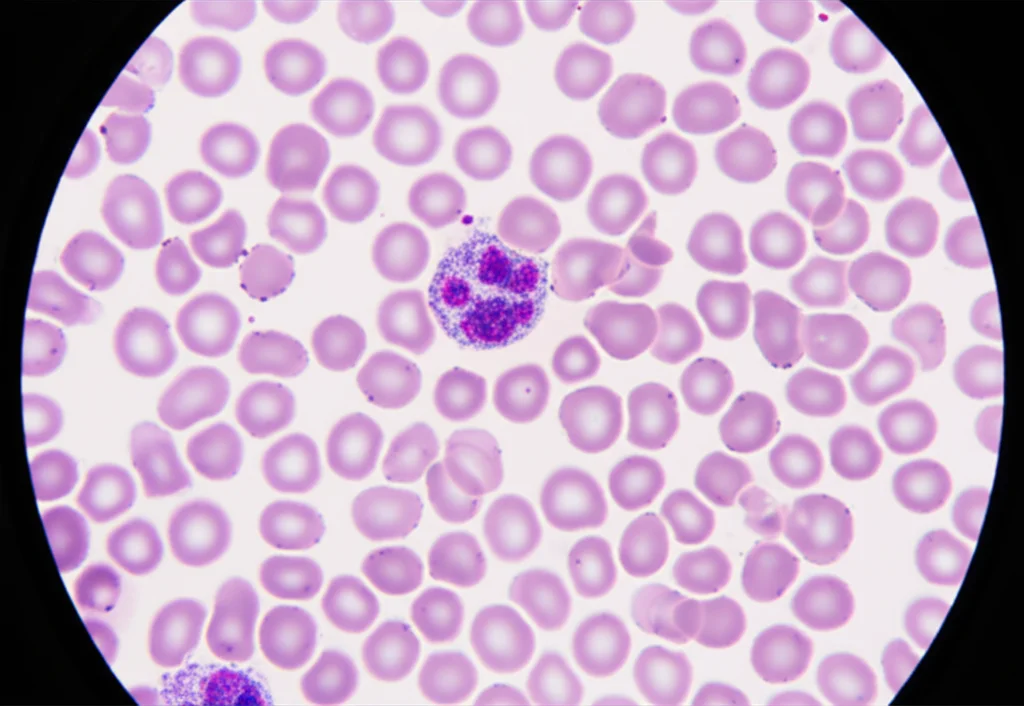

To do this, we didn’t go out and collect new data ourselves. Instead, we used information from three big surveys already done in Rwanda: the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 2010, 2014-15, and 2019-20. These surveys are awesome because they collect tons of data on health, population, and nutrition across the country. We focused on children aged 6 to 59 months who were tested for malaria (using blood smears) and had their height and weight measured.

We pulled data from over 10,000 children who were tested for malaria and over 11,000 who had nutritional measurements. The sample size was robust, giving us confidence in the findings. We looked at different nutritional indicators – stunting, wasting, and underweight – and checked if they were associated with testing positive for malaria without symptoms. We used statistical methods, specifically logistic regression, to calculate the odds of having asymptomatic malaria if a child was undernourished. We did this first without considering other factors (unadjusted) and then adjusted for things that might also influence malaria risk, like the child’s age, gender, where they lived (rural/urban, region), their mother’s education level, and the family’s wealth. This helped us see the relationship more clearly, trying to isolate the effect of nutrition.

What We Found: Some Eye-Opening Connections

Okay, so what did the data tell us? First off, asymptomatic malaria was present in about 1.3% of the children tested across the surveys. That might sound low, but remember, these are kids who *aren’t* showing symptoms, so they’re not getting treated, and they can still spread the parasite. It’s a significant reservoir for transmission.

When we looked at nutrition, we found that a pretty large proportion of children were stunted – about 38.3% across the survey periods. Wasting and underweight rates were lower but still present.

Now for the associations:

- We found that children who were stunted were more likely to have asymptomatic malaria. The odds were significantly higher for them compared to non-stunted children.

- Being underweight was also associated with an increased prevalence of asymptomatic malaria, even after adjusting for other factors.

- Age mattered a lot! Older children (over 24 months) were significantly more likely to have asymptomatic malaria than younger ones. We think this might be because they have more exposure to mosquito bites as they get older and maybe sleep less consistently under bed nets than infants who share a bed with their mothers. Also, older children in high-transmission areas start developing some immunity, which can lead to asymptomatic infections rather than symptomatic ones.

- The family’s wealth made a big difference. Children from the richest families were significantly less likely to have asymptomatic malaria compared to those from poorer families. This isn’t surprising, as wealth often correlates with better housing, access to healthcare, and ability to afford preventive measures.

- We also saw a strong link with anaemia. Children with anaemia were much more likely to have asymptomatic malaria. This makes sense, as malaria is a known cause of anaemia, creating a bit of a vicious cycle.

- Interestingly, in the 2015 data, we saw a potential negative correlation with iodine supplementation (indicated by iodine in household salt). Children from households using iodized salt seemed to have a lower prevalence of asymptomatic malaria. This is intriguing and definitely warrants more research!

Wasting didn’t show a consistent significant association with asymptomatic malaria in the adjusted analysis across all surveys combined, although stunting and underweight did.

Rwanda’s Efforts: A Foundation of Progress

It’s important to put these findings into context. Rwanda has been actively fighting both malaria and malnutrition for years. After facing major challenges in the 1990s, they’ve really rebuilt their health system. They’ve decentralized healthcare, pushing services closer to communities. They’ve got dedicated agencies like the National Child Development Agency (NCDA) specifically focused on ending malnutrition and stunting. Initiatives like the 1000 Days Campaign, promoting better care and feeding for young children, and programs like “Kitchen Gardens” (Akarima Kigikoni) and “One Cow Per Poor Family” (Girinka) aim to improve household food security and nutrition.

On the malaria front, they’ve scaled up proven interventions like insecticide-treated bed nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS). Community Health Workers (CHWs) are absolutely crucial in delivering these services, reaching families directly, testing for malaria, and ensuring treatment.

These policies and interventions have clearly had a positive impact, contributing to the observed declines in both stunting and malaria prevalence over the years covered by the DHS data. However, our study highlights that despite this progress, the link between undernutrition and the *hidden* burden of asymptomatic malaria persists.

Connecting the Dots: The Vicious Cycle

So, what does this all mean? Our findings reinforce the idea that nutrition and malaria are deeply intertwined. Undernutrition weakens a child’s immune system, making them more vulnerable to infections, including malaria. And malaria, even the asymptomatic kind, can worsen nutritional status by affecting appetite, how the body uses nutrients, and potentially causing nutrient loss. It’s a classic vicious cycle.

This study specifically focusing on asymptomatic malaria is key because these cases are often missed by routine health services focused on treating sick children. By identifying that undernourished children are more likely to carry these silent infections, it tells us that focusing solely on symptomatic cases isn’t enough to break the cycle of transmission, especially in vulnerable populations. Socioeconomic factors, like how wealthy a family is and the mother’s education level, also play a significant role, influencing both nutrition and access to malaria prevention.

While Rwanda has seen great progress, the rates of stunting are still higher than the global average. And events like the COVID-19 pandemic have shown how fragile these gains can be, potentially reversing progress. This underscores the need for continued, integrated efforts.

Challenges and Looking Ahead

Of course, like any study, ours had limitations. We used existing data from surveys, which gives us a snapshot in time (cross-sectional) rather than following the same children over time (longitudinal). A longitudinal study would be better for understanding cause and effect – does undernutrition *cause* asymptomatic malaria, or does asymptomatic malaria *cause* undernutrition, or is it a complex back-and-forth influenced by many things? Our study shows a strong association, but doesn’t definitively prove causality.

Also, we focused only on asymptomatic malaria. Including symptomatic cases would give an even fuller picture of how nutrition impacts overall malaria risk. Future research really needs to use longitudinal designs and look at both types of malaria to build stronger evidence.

We also think it’s super important for future surveys and studies to dig deeper into specific dietary factors and micronutrient deficiencies. Could a lack of certain vitamins or minerals be particularly linked to asymptomatic malaria? The potential link with iodine is fascinating and needs more investigation.

Finally, our findings about age, wealth, and regional differences highlight that interventions need to be targeted. Older children, those from poorer families, and those in specific high-transmission regions might need extra attention. Education for mothers also seems important, likely influencing both nutrition practices and health-seeking behaviors.

The Big Takeaway

The association between nutrition and malaria, especially the often-overlooked asymptomatic kind, is a critical piece of the puzzle in improving child health in Rwanda and similar settings. Our study, using valuable DHS data, confirms that undernutrition, particularly stunting and underweight, is significantly linked to asymptomatic malaria in young children. This isn’t just about treating sick kids; it’s about improving overall health and resilience. Integrating nutrition programs with malaria control efforts is absolutely essential to break the vicious cycle and protect the most vulnerable children.

Source: Springer