Beyond Small Talk: How Robots Are Learning What Truly Matters to You

Hey There, Let’s Talk About Robots!

So, you know how we’re all getting used to chatting with machines? Whether it’s asking Siri the weather or getting help from a customer service bot, these conversational systems are popping up everywhere. They’re getting pretty good, too, especially when they’re designed to help you do something specific, like booking a train ticket or finding information. That’s the “task-oriented” stuff.

Then there are the bots that are just there to chat, to keep a conversation going. Think of them as digital companions. For these guys, making the chat feel natural and, importantly, making *you* feel understood is the big goal. And that’s where personalization comes in. Making a system adapt to the person it’s talking to? Turns out, that’s super effective. It can help with things like reducing stress or just making recommendations you actually like.

But here’s a thought: while we’ve been teaching robots to remember your name or your favorite color, there’s a whole deeper layer to us humans that hasn’t really been tapped into. I’m talking about our values. You know, those core beliefs and concepts that guide *everything* we choose and evaluate in life? They’re a massive part of who we are and how we interact with the world (and each other!).

Why Values? They’re Kind of a Big Deal!

Think about it. Values influence our behavior, our morals, how we build relationships, even how we communicate with people from different walks of life. Understanding someone’s values is key to really “getting” them. So, it stands to reason, if a dialogue system could understand *your* values, the conversation could get a whole lot more meaningful, right?

That’s exactly what this study dives into. The idea was to build a system that doesn’t just chat, but actually tries to figure out what makes you tick at a fundamental level – your values – just by talking to you. And then, to see what happens when the robot actually *uses* that understanding in the conversation. Would it make the interaction better? Would it change how you feel about the robot? Could it even help *you* understand yourself better?

The big contributions they were hoping for were:

- Coming up with a way for a robot to estimate your values just from chat.

- Showing that this method could make you feel better about the robot.

- Showing that it might even help you get new insights into your *own* values.

Pretty cool goals, if you ask me!

Building a Robot That Gets You

Okay, so how do you build a robot that can understand something as complex as human values? It’s not like you can just ask, “Hey, what are your top 3 values?” and get a straightforward answer. Values are often intertwined with our preferences and the reasons *why* we have those preferences.

The researchers leaned on a concept called the Means-End Chain model. It’s a theory that links our choices (like preferring a certain hobby) to the consequences of those choices, and ultimately, to our core values. The classic way to explore this is with a technique called “laddering,” where you keep asking “why is that important to you?” over and over.

In this study, they adapted this for robot chat. They focused on preferences, specifically hobbies, because hobbies are common conversation starters and reveal a lot about what someone likes and *why*. The model links your preferences to values through the *reasons* you give for liking them. So, the robot would ask about your hobbies and then, crucially, ask *why* you like them.

To figure out the values from these reasons, they used a Large Language Model (LLM) – think of it like a super-smart text AI, like GPT-4. They fed the LLM the user’s preference and the reason for it (e.g., “I like hiking because it helps me feel free”) and asked it to estimate which values from a standard list (like self-direction, security, hedonism, etc., based on Schwartz’s theory of values) were reflected in that statement, giving percentages for each.

Now, one preference only gives you a piece of the puzzle. Our values connect to *multiple* things we like or dislike. To see the bigger picture and find patterns, they used something called an Infinite Relational Model (IRM). This is a fancy way of saying it helps cluster related things together without needing to know beforehand how many groups there will be. It looks at the relationships between your different preferences and the values estimated for each, helping to group preferences that might stem from similar underlying values.

So, the process goes: chat about hobbies -> get reasons -> use LLM to estimate values for *each* reason -> use IRM to find patterns and clusters across multiple preferences -> use these insights to inform the conversation.

They even used prompts to guide the LLM, like telling it, “You are an expert in estimating values,” and giving it the list of values and the user’s statement. This helps the LLM give structured, relevant outputs.

Because asking about tons of hobbies can get tiring, the system also used the LLM to *predict* other hobbies you might like or dislike based on the initial ones. This way, they could build a richer user model with less direct questioning.

Chatting About What Matters

The conversation flow was designed in two parts. First, the robot collected information about preferences (hobbies and reasons). While the robot was busy using LLMs and IRMs in the background to build the user model, it would keep the conversation going with simple, context-aware questions generated by the LLM.

Once the model was built (after discussing about four preferences and predicting many more), the conversation shifted to values. This is where the robot would actually *use* the estimated values. They prepared different ways the robot could bring up the values:

- Mentioning the single value that seemed strongest overall.

- Talking about values linked to specific *clusters* of preferences the IRM found.

- Discussing values that corresponded to the higher-order value categories (like ‘Openness to Change’ or ‘Conservation’) that the IRM clusters matched.

Crucially, the robot didn’t just state, “You value X.” It framed these as observations or questions, like, “Earlier, you mentioned you like [preference] because of [reason]. Hence, I thought you value [estimated value]. Am I right?” or “Thus, you value [estimated value], right?” This makes it a collaborative exploration rather than a lecture.

They even paraphrased the sometimes-academic value labels (like ‘Hedonism’ or ‘Self-Direction’) into more everyday language so the conversation felt natural.

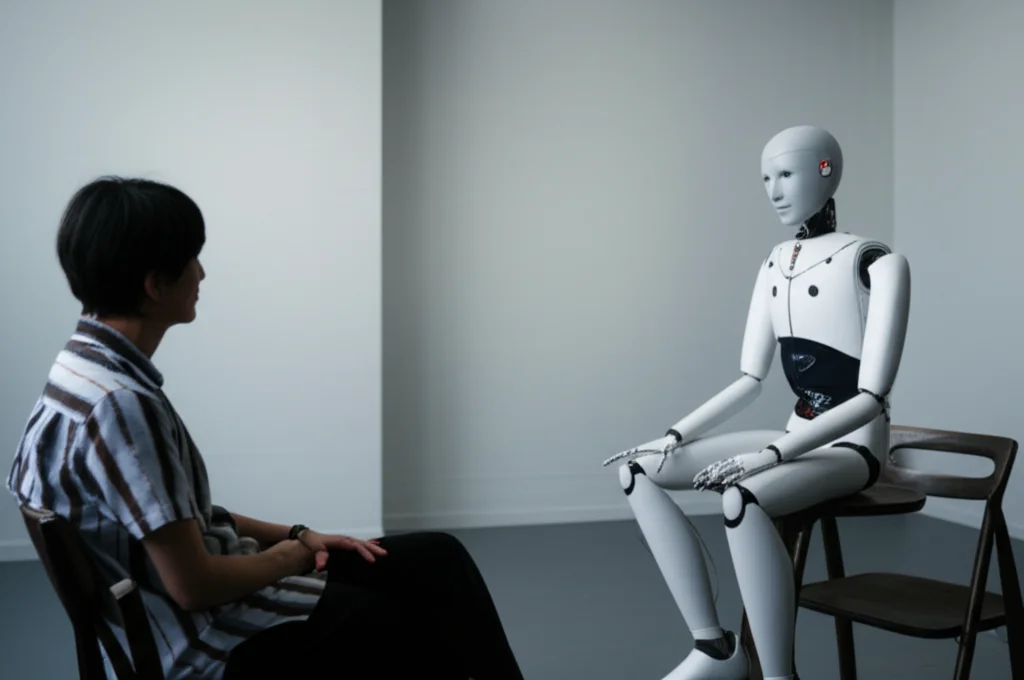

The robot they used for the experiment was a humanlike android called Geminoid F. Why an android? Well, studies suggest people feel more comfortable discussing personal things like hobbies with robots that look more human. Plus, humanlike robots can feel more like social partners, which is important for deep conversations about values.

To make sure the conversation flowed smoothly, especially during the parts where the robot was thinking or the user might pause to reflect on their values, they used the Wizard of Oz (WoZ) method. This is a common technique in human-robot interaction where a human operator secretly controls some aspects of the robot’s responses or turn-taking to prevent awkward silences or breakdowns, making the interaction feel more natural to the participant.

Putting It to the Test: The Experiment

To see if all this value-understanding tech actually made a difference, they set up an experiment. Participants had conversations with the Geminoid F robot under three different conditions:

- Condition 1 (C1): The robot used the proposed method to estimate the user’s values and talked about those estimated values.

- Condition 2 (C2): The robot talked about values, but they were randomly selected, not based on the user’s input. This helped check if just *mentioning* values had an effect (like the Barnum effect, where vague statements feel accurate).

- Condition 3 (C3): The robot only talked about preferences (hobbies) and didn’t mention values at all. This was the baseline.

Each participant did conversations under different conditions (the order was mixed up). They were told the robot was an assistant trying to understand them. After each chat, participants filled out questionnaires about their experience.

They measured a bunch of things to test their hypotheses:

- How accurate the robot was at guessing the user’s preferences and values.

- How much the user agreed with the robot’s statements about their values.

- How they felt about the *quality* of the dialogue (was it easy to understand, did the robot seem to want to understand them, etc.).

- Their impression of the robot itself (using the GodSpeed questionnaire, which measures things like how humanlike, alive, likable, and intelligent the robot seemed).

- How close they felt to the robot (using the IOS scale).

- Whether the conversation gave them *new insights* into their own hobbies or values.

They had 35 participants complete the study, mostly young adults (average age around 21).

So, What Did We Find Out?

The results were pretty interesting! Let’s break it down:

- Could the robot estimate values? (H1) YES! The robot’s estimation accuracy for preferences was decent (around 64%), better than chance. More importantly, when the robot made statements about the user’s values based on its estimation (C1), the users agreed with those statements significantly more often than when the robot talked about random values (C2). This supports the idea that the method works.

- Did it improve dialogue quality? (H2) NOT REALLY. Based on the questionnaires, there wasn’t a big difference in how people rated the overall quality of the conversation across the three conditions.

- Did it enhance the robot’s impression? (H3) PARTIALLY YES! This is where it gets cool. While the robot didn’t seem more humanlike or likable just by talking about values, it *did* seem more animacy (like it was alive or had intentions) and more perceived intelligence in the condition where it used the estimated values (C1) compared to the others (C2 and C3).

- Did it deepen the relationship? (H4) NO. The short conversation didn’t seem to make people feel significantly closer to the robot.

- Did it deepen user self-understanding? (H5) YES! This is another big win. Participants in the condition where the robot discussed their estimated values (C1) reported gaining significantly more *new insights into their own values* compared to the other conditions (C2 and C3). The robot talking about their values helped them reflect on themselves.

Why Does This Matter?

Even though the dialogue quality and relationship didn’t see huge jumps in this specific experiment, the fact that the robot seemed more animacy and had higher perceived intelligence when it understood values is a big deal in human-robot interaction (HRI). When a robot feels more alive and smart, it can build more trust and be more accepted. Imagine a robot assistant that feels like it’s actually *thinking* about you and your motivations – that’s a step towards a more natural and effective partnership.

The most exciting finding, for me, is the new insights into users’ own values. The robot basically acted like a mirror, reflecting back aspects of the user’s internal world they might not have consciously articulated before. This aligns with the idea of “constructive interaction,” where talking things through with someone (or something!) helps you clarify your own thoughts. A robot that helps you understand *yourself* better? That’s pretty profound and opens up possibilities for robots in areas like coaching, therapy support, or even just personal reflection.

Why didn’t dialogue quality or relationship improve? Well, maybe talking explicitly about values isn’t how humans usually chat. We often show our values rather than stating them outright. The way the robot phrased things might need tweaking to feel more natural. Also, building a real relationship takes time, and these were short interactions. Plus, the robot didn’t share *its* values, and similarity in values is known to be important for human relationships.

The Road Ahead

This study is a fantastic first step, but there’s always more to explore. Future work could look at making the value estimation even faster, maybe by considering broader social or cultural values. They could also try different ways the robot could *use* the estimated values in conversation – maybe more subtly, or by sharing its own (programmed) values. Applying this method to more free-flowing, unstructured conversations is another challenge.

They also want to see if the type of robot matters. Would a different looking robot have a different impact? And how many preferences does the robot really need to ask about to get a good sense of your values without making the conversation feel like an interrogation?

Overall, this research shows that moving beyond just remembering facts about a user and starting to understand their core values can make conversational robots more effective and lead to richer interactions, potentially even helping us learn a little more about ourselves along the way. It’s an exciting direction for the future of AI and robotics!

Source: Springer