A Shot of Hope? Ranibizumab for ROP in Tiny Eyes

So, we’re diving into a really important topic today: saving the sight of our tiniest heroes – premature babies. One of the big challenges they face is something called Retinopathy of Prematurity, or ROP. It’s a bit of a mouthful, but essentially, it’s a problem with how the blood vessels in their eyes grow. Sometimes, they don’t grow properly, and in severe cases, this can lead to blindness. Scary stuff, right?

What Exactly is ROP?

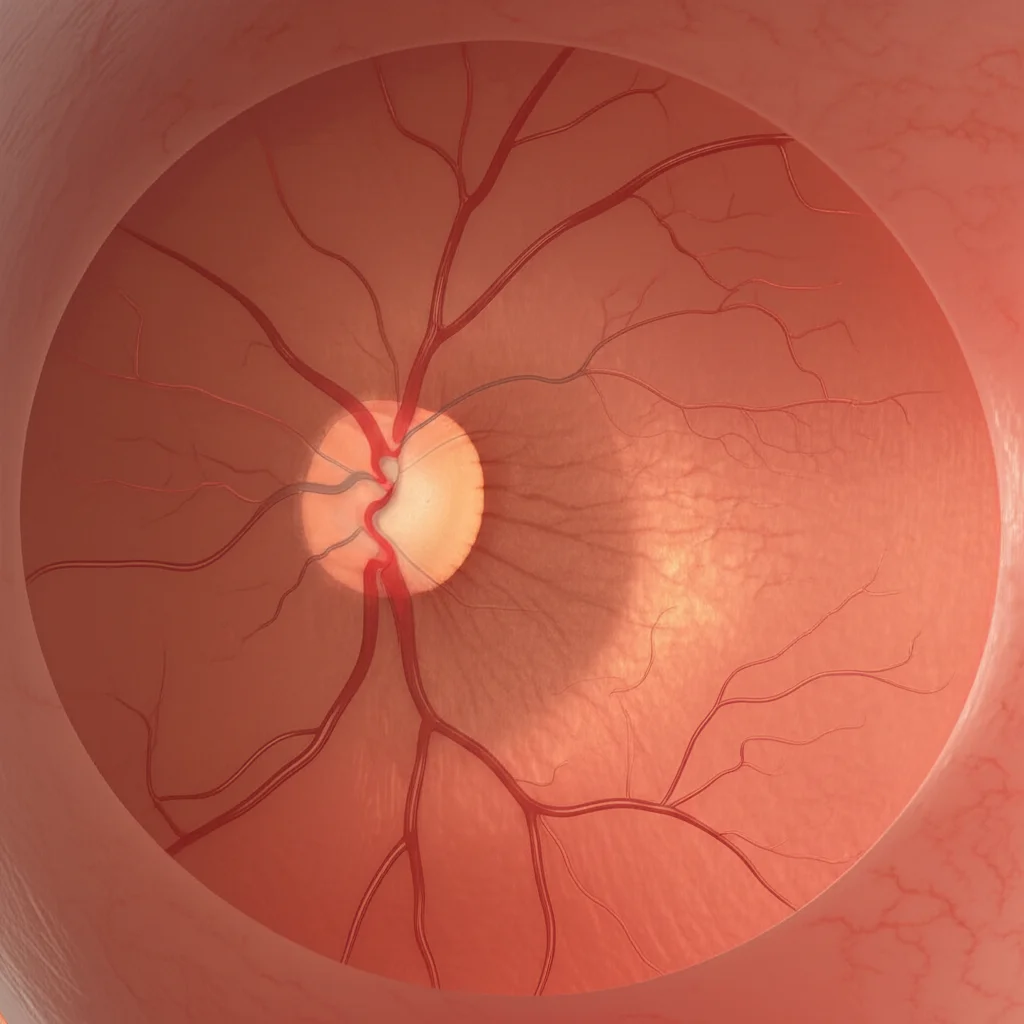

Picture this: When babies are born too early, their eyes aren’t quite finished developing, especially the blood vessels in the retina. The retina is like the film in a camera, at the back of the eye, capturing images. In ROP, these vessels can grow in a messy, abnormal way, sometimes pulling on the retina and causing it to detach. This is particularly risky in certain zones of the retina and at specific stages of the disease. This study specifically looked at ROP in Zone II, Stage 2, with something called “plus disease” – which basically means the blood vessels are looking really swollen and twisted, a sign things are getting serious. Let’s call it ROP II2+ for short.

The Traditional Approach and Why We Need Alternatives

For a long time, the go-to treatment to stop ROP from getting worse was laser photocoagulation (LPC). It works by zapping the abnormal areas to stop the vessel growth. And hey, it’s effective at preventing detachment. But, let’s be honest, it’s not without its downsides. We’re talking potential side effects like losing some peripheral vision and ending up with significant myopia (nearsightedness). Not ideal, especially for little ones who have their whole lives ahead of them.

This is where newer treatments come into play, specifically anti-VEGF therapies. VEGF stands for Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, a protein that tells blood vessels to grow. In ROP, there’s too much of this stuff, causing the abnormal growth. Anti-VEGF drugs are designed to block this protein.

Enter Ranibizumab

You might have heard of some of these anti-VEGF drugs, like bevacizumab. It was one of the first used for ROP and showed promise, especially for severe ROP in the central zone (Zone I). But there were some worries about its potential long-term effects on development because it hangs around in the body for a while.

That’s why folks got interested in other options, like ranibizumab. It’s another anti-VEGF drug, but here’s the key difference: it’s a smaller molecule and has a shorter half-life. This means it clears out of the system faster, potentially making it a safer bet for tiny, developing bodies.

There was a big study called RAINBOW that showed ranibizumab worked just as well as laser for certain types of ROP, with better structural outcomes and less myopia. Pretty compelling! But – and this is a big “but” – that study *didn’t* include the specific type we’re talking about: ROP II2+. So, we really needed to know how ranibizumab performs for *this* particular group.

What This Study Looked At

This study, looking back at cases treated at Tokai University hospital, aimed to fill that gap. They wanted to see how effective intravitreal injections of ranibizumab (IVR) were as the *first* treatment for ROP II2+. They followed these little patients for at least a year and focused on two main things:

- Reactivation: Did the ROP come back and need more treatment after the initial injection?

- Persistent Avascular Retina (PAR): Were there still areas in the outer retina that never fully developed blood vessels a year later?

They also poked around to see if any factors, like how big the baby was at birth, were linked to these outcomes.

The Results Are In

Okay, so what did they find? They looked at 30 eyes from 16 infants who got the ranibizumab injection as their first treatment for ROP II2+.

Here’s the good news: For over a year after that first shot, *all* the eyes stayed in remission with just the ranibizumab. That’s fantastic! It means the initial treatment did its job in calming things down.

But, as is often the case in medicine, there are nuances. Turns out, 40% of these eyes needed *another* treatment because the ROP flared up again (reactivation). The median time until this happened was about 70 days. So, while the first shot worked initially, it wasn’t a one-and-done deal for everyone.

And what about PAR? A year after the first injection, PAR was present in 11 out of the 30 eyes. It was actually much more common in the group that experienced reactivation.

What Does It All Mean?

This study gives us some valuable insights. First off, it supports the idea that ranibizumab is indeed effective for ROP II2+, at least in the short term (up to a year). It can successfully get the disease under control.

However, it also highlights the challenges: reactivation is a real possibility, happening in a significant chunk of cases (40%). This means babies treated with ranibizumab need careful, ongoing monitoring.

The link they found between lower birth weight and both the tendency for reactivation and the significant association with PAR is super interesting. It suggests that tinier babies might be at higher risk for these specific outcomes after ranibizumab treatment. This could potentially help doctors identify which babies might need even closer follow-up or maybe a different treatment strategy down the line.

Comparing ranibizumab to laser again, this study echoes what others have found: ranibizumab seems great for preventing the vision problems associated with laser, but it might come with a higher risk of the ROP coming back. Some experts even suggest that if ROP *does* reactivate after ranibizumab, maybe following up with laser is a good idea. This could potentially give the best of both worlds – avoiding the initial laser side effects while still ensuring the retina is stabilized long-term and potentially reducing the amount of drug needed.

The presence of PAR is another thing to keep an eye on. While some research suggests it might just be part of how ROP naturally resolves in some cases, others show it’s more common after anti-VEGF treatment. We don’t fully know the long-term implications of PAR yet, so continued monitoring is key.

The Road Ahead

Now, let’s be honest, this study has some limitations. It’s a look back at past cases from just one hospital, and the number of babies included isn’t huge. They also only followed the babies for one year. ROP can sometimes cause problems years down the road, so we need longer-term studies to really understand the full picture, including the long-term effects of PAR and whether birth weight truly is a reliable predictor for everyone.

Wrapping Up

So, what’s the big takeaway? Ranibizumab is a valuable tool in our fight against ROP II2+. It’s effective at getting the disease under control for at least a year and offers potential advantages over laser in terms of vision quality. But we absolutely need to be vigilant. Reactivation is common, and PAR is frequently seen, especially in those who reactivate. The finding about lower birth weight being linked to these outcomes is a crucial piece of the puzzle that could help us better manage these tiny patients. It’s a complex picture, but every study like this brings us closer to finding the best ways to protect the precious sight of premature infants.

Source: Springer