Scanning the Future: Can CT Predict RA-ILD Progression?

Hey There, Let’s Talk Lungs and RA!

So, you know how Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is mostly famous for messing with your joints? Well, it’s a bit of a sneaky systemic disease, meaning it can sometimes affect other parts of your body too. And one of the places it can unfortunately show up is in your lungs, leading to something called Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD). When RA and ILD team up, we call it RA-ILD.

Now, RA-ILD is a big deal because it can really impact how well you breathe, and its path is, frankly, unpredictable. Some people might have a mild case that stays stable, while for others, it can get worse pretty quickly. This got me thinking, and clearly, it got some clever researchers thinking too: wouldn’t it be amazing if we could figure out *who* is likely to see their RA-ILD progress? That way, doctors could step in earlier or manage things differently.

The Challenge of Seeing Inside

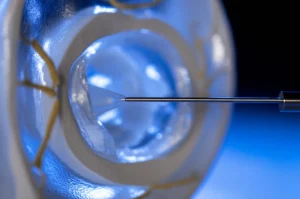

Right now, a key tool for looking at the lungs in RA-ILD is a special type of scan called a High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT). These scans give doctors a detailed look at the lung tissue. They’re super important for spotting ILD and seeing what pattern it’s making (like scarring or inflammation). But here’s the tricky part: interpreting these scans can be a bit subjective. What one doctor sees or scores might be slightly different from another, or even the same doctor on a different day. This subjectivity can make it harder to get a truly objective picture of how much disease is there or if it’s changing.

Because of this, scientists have been exploring more objective ways to analyze these scans. There are “semi-quantitative” methods, which use standardized scoring systems (like the Goh and Warrick methods mentioned in the study) to try and add a bit more structure to the visual assessment. And then there are “quantitative” methods, which use computer software to measure things like lung density and volume automatically. Think of it like the difference between estimating how much liquid is in a glass by looking (subjective), using marked lines on the glass (semi-quantitative), or pouring it into a measuring cup (quantitative).

Asking the Big Question

The folks behind this particular study wanted to dive into this. They asked a couple of key questions:

- How well do these objective (quantitative) measurements line up with the more traditional, standardized visual scores (semi-quantitative)?

- More importantly, can either the semi-quantitative scores or the quantitative measurements from an early scan predict whether a patient’s RA-ILD will get worse over time?

They looked back at the records of 77 patients with early-stage RA-ILD (meaning their first follow-up scan was within 5 years of the baseline scan). They analyzed the baseline and follow-up HRCT scans using both the semi-quantitative Goh and Warrick scoring systems and the quantitative Vitrea software to measure lung density volumes (Low, Medium, High Density Volumes – LDV, MDV, HDV) and Mean Lung Attenuation (MLA).

What Did They Find? (The Results Are In!)

Okay, let’s get to the good stuff – what did the study reveal? They found that about 44% of the patients in their group showed signs of disease progression over a median follow-up of 20 months. Progression was defined based on worsening symptoms, lung function tests, or radiological changes.

Here’s the scoop on their findings:

- Correlation is Key (for Extent): The quantitative measurements (like MLA and HDV) showed pretty strong correlations with the semi-quantitative scores (Goh and Warrick), especially on the follow-up scans. This is cool because it suggests that the automated software is actually doing a good job of measuring the *extent* of the disease in a way that aligns with how experts score it visually. It validates the idea that these quantitative methods can offer a standardized, objective way to assess how much lung is affected.

- The Prediction Puzzle: Now, here’s where it gets interesting, and maybe a little surprising. When they crunched the numbers to see what factors predicted progression, they found that *neither* the baseline semi-quantitative scores *nor* the baseline quantitative measurements were independent predictors of whether the disease would get worse.

- Enter the UIP Pattern: So, what *did* predict progression in this study? It turns out, the presence of a specific pattern on the initial HRCT scan, called the Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP) pattern, was the *only* independent predictor. Patients with the UIP pattern at baseline were significantly more likely to experience progression.

They did note that some baseline and follow-up quantitative parameters (like baseline MDV and follow-up MLA/LDV) were different between the groups that progressed and those that didn’t, but these differences didn’t hold up as independent predictors when other factors were considered in the statistical model.

So, What Does This All Mean?

This study gives us some valuable insights. First off, it reinforces that the UIP pattern seen on HRCT is a really important red flag for potential progression in RA-ILD, even in the early stages. This pattern is characterized by specific features like honeycombing, which suggests more established scarring.

Secondly, it tells us that while quantitative methods are great for objectively measuring the *amount* of disease and correlate well with traditional scoring systems, they didn’t predict progression in this specific group of *early-stage* RA-ILD patients. The researchers suggest this might be because in the very early stages, the fibrosis might be minimal, and the histogram-based quantitative methods used here might not be sensitive enough to pick up the subtle differences that foretell future worsening.

Think of it like trying to predict if a small crack in a wall will spread. A ruler might tell you exactly how long the crack is (quantitative extent), but maybe only looking closely at the *type* of crack and the *material* of the wall (pattern) tells you if it’s likely to get bigger.

Looking Ahead

Even though the quantitative methods didn’t predict progression here, the study authors are quick to point out their potential. They offer a standardized, objective way to assess disease extent, which is super helpful for monitoring patients over time and could reduce the variability that comes with purely visual assessment. This could free up radiologists’ time and provide consistent data.

The study does have its limitations, as most studies do. It was retrospective, meaning they looked back at existing data, which can sometimes lead to missing information (like complete PFT data for everyone). The follow-up period was also relatively short (around two years on average), and the study might not have had enough power to detect more subtle predictive signals from the quantitative parameters.

The Bottom Line

For now, seeing that UIP pattern on an early scan seems to be the strongest indicator of future progression in RA-ILD, according to this study. But don’t count out the quantitative methods! They’re fantastic tools for objective assessment and monitoring the *extent* of the disease. This research highlights that we still need to refine how we use these tools, perhaps exploring different types of quantitative analysis (like texture-based methods) or studying larger groups over longer periods, especially focusing on those crucial early stages. The goal is always the same: to get better at identifying patients at risk so we can give them the best possible care.

Source: Springer