QPID: Seeing Radiation in a Whole New Light for Medicine

Hello there! Let me tell you about something pretty exciting we’ve been working on.

You know how sometimes doctors or scientists need to see where radioactive stuff goes inside the body or a tissue sample? It’s a big deal for understanding how potential treatments or diagnostic agents work. Traditionally, this was done with something called autoradiography. Think of it like a super old-school camera film that gets exposed by radiation, showing you a blurry picture of where the radioactive bits landed. It’s been around forever – literally since Becquerel noticed uranium fogging up photographic plates back in 1896!

Over the years, this technology got more sophisticated, moving into the digital age with sensors that can pick up ionizing radiation. Some cool systems came along, like those using sensitive films with digital cameras or gas chambers that detect the trails left by particles. These were steps forward, giving us digital images and faster detection times compared to the old film method. But, frankly, they had their limits. They might be great at seeing *where* particles hit, but they often struggled with telling *what kind* of particle it was, how much energy it had, or if multiple types of radiation were present at the same time.

Enter QPID: Our Game-Changing System

That’s where our new system comes in – we call it QPID, which stands for Quantitative Particle Identification spectral autoradiography. We think it’s a real paradigm shift! At its heart, QPID uses a super-sensitive silicon detector called the Timepix3 sensor, originally developed by the folks at CERN (yes, the particle physics people!). This isn’t just any detector; it’s pixelated, meaning it’s like a grid of tiny sensors, and it’s incredibly fast and smart.

Here’s the cool part: the Timepix3 doesn’t just say “a particle hit here.” For *each* particle that passes through, it can measure how much energy was deposited and *exactly* when it happened, down to a few nanoseconds! By looking at which pixels were hit and when, we can actually reconstruct the path, or “track,” the particle took through the sensor. This gives us a wealth of information about the particle itself.

But we didn’t stop there. We coupled the Timepix3 with a separate crystal detector that’s great at spotting gamma rays. Why? Because some radioactive decays emit a charged particle *and* a gamma ray almost simultaneously. By synchronizing the Timepix3 and the gamma detector with a common clock, we can look for these “coincident” events – a particle track on the Timepix3 happening at the same time as a gamma ray in the crystal. This is a powerful way to identify *exactly* which radioisotope caused the event, especially useful for distinguishing between different types of radiation or even different decay pathways of the same isotope.

So, with QPID, we’re not just getting a picture of where the radiation is; we’re getting a detailed map that tells us:

- What kind of particle it was: Alpha, beta (plus or minus).

- How much energy it deposited: Giving us spectral images.

- When it happened: With incredible timing precision.

- If it was accompanied by a gamma ray: Crucial for specific isotope identification.

Putting QPID to the Test

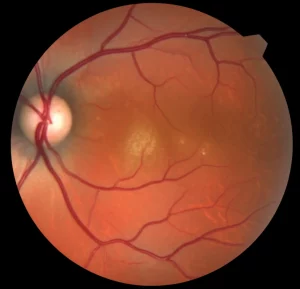

We were eager to see what QPID could do, so we ran a couple of studies. First, we looked at how special immune cells, called T cells, labeled with a radioisotope called 89Zr, distributed themselves in a mouse spleen. Being able to see exactly where these cells go at a microscopic level is vital for understanding how they interact with tissues and potential diseases.

The second study was perhaps even more exciting. We took a bone sample from a mouse that had been given *two* different radioactive substances known to target bone: 223RaCl2 (which emits alpha particles) and Na18F (which emits positrons, a type of beta particle, followed by gamma rays). These are relevant to new cancer therapies that use radiation delivered directly to tumors or affected areas (like bone metastases).

With QPID’s particle identification filters, we could take the data from this single sample and generate *two separate images*: one showing only where the 223Ra was and another showing only where the 18F was! This dual-isotope imaging capability, especially separating alpha and beta+ emitters, is something traditional autoradiography systems just can’t do effectively, particularly with the gamma coincidence tagging for the beta+.

We could also use the spectral information (the energy deposited by the particles) to improve image quality. For instance, with the 89Zr-labeled T cells, we could filter the data to only show events from low-energy beta particles, which have shorter tracks and give a sharper image of the cell location, compared to the blurrier image you get from including higher-energy particles with longer tracks.

Why This Matters for Medicine

Okay, so we have this fancy new detector that gives us lots of data. Why is this a big deal? Well, it opens up some really important possibilities, especially for personalized medicine and cancer treatment.

- Seeing Two Things at Once: The ability to image two different radioisotopes in the same tissue sample simultaneously is huge. Many new cancer treatments use “theranostic” agents – one version for imaging (like 18F) and a similar version for therapy (like 223Ra). Being able to see where *both* go in the same tissue helps researchers understand how the therapeutic dose is distributed relative to the imaging signal. This is crucial for predicting how effective the treatment will be and minimizing side effects.

- Quantitative Data: QPID provides quantitative measurements – we can actually measure the activity (how much radioactive stuff is there) and even the deposited energy (related to the radiation dose) in specific areas of the tissue. This goes way beyond just seeing “where” the radiation is; it tells us “how much” and “what kind,” which is essential for accurate dosimetry (calculating the radiation dose delivered to the tissue).

- Microdosimetry: By measuring the energy deposited by individual particles, QPID helps bridge the gap between understanding radiation effects at the microscopic level (single cells, small tissue structures) and the macroscopic level (whole organs, the entire body). This is a critical step towards developing more accurate models for predicting radiation dose in patients, leading to more personalized and effective radiopharmaceutical therapies.

- Particle Identification: Knowing *what kind* of particle is delivering the dose is vital because different particles (alpha vs. beta) deposit energy differently and have different biological effects. QPID’s ability to distinguish them, especially using gamma coincidence for beta+, is a unique advantage.

How It’s Built and How It Works (A Little More Detail)

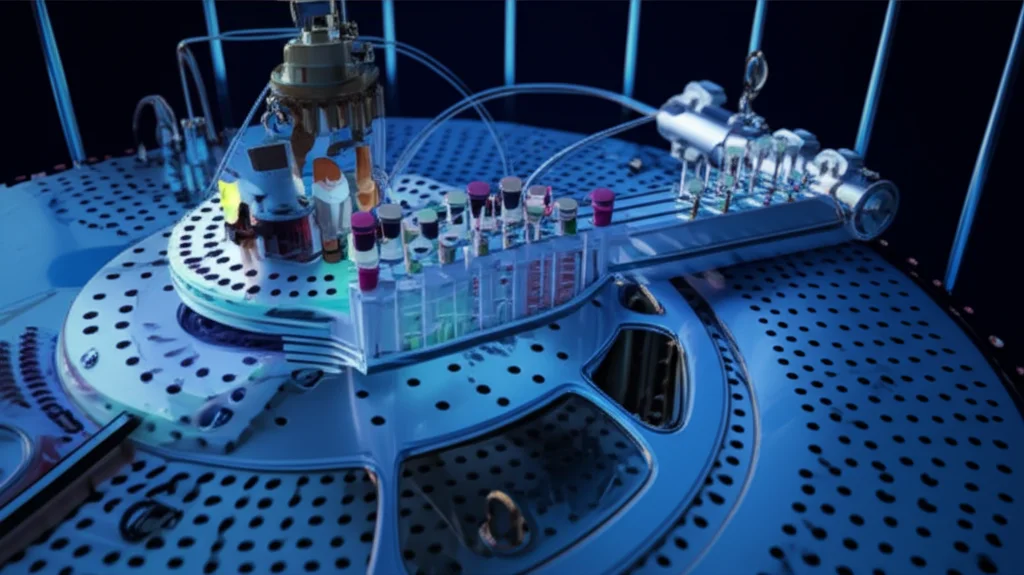

The QPID system is a combination of several key pieces of hardware working together seamlessly:

- The Timepix3 Sensor: This is the heart of the system for detecting charged particles (alphas and betas). It’s a 256×256 pixel silicon detector, about as thick as a few sheets of paper. When a charged particle hits it, it creates a tiny electrical signal in the silicon, which is picked up by the electronics under each pixel. The Timepix3 chip records the time and energy deposited for *each* pixel hit, independently.

- The CeBr3 Crystal Detector: This crystal is designed to detect gamma rays. When a gamma ray hits it, it produces a tiny flash of light (scintillation), which is then converted into an electrical signal by a photodetector.

- The Digitizer and External Clock: These are the brains and the conductor. The digitizer reads the signal from the gamma detector very quickly. A custom-built external clock ensures that both the Timepix3 and the digitizer are perfectly synchronized. This synchronization is what allows us to look for events happening at the *exact* same time – the key to our gamma coincidence detection.

To image a tissue sample, we place a thin slice (like 10 to 50 microns thick) directly on top of the Timepix3 sensor, with a thin protective film in between to prevent contamination. We then acquire data simultaneously from both the Timepix3 (particle tracks) and the gamma detector (gamma rays). Software then processes this “list mode” data, reconstructing particle tracks, estimating their energy and time, and looking for coincidences between particle tracks and gamma rays within a very narrow time window (we set it to 60 nanoseconds).

Based on this processed data, we can apply different filters:

- Filter by energy: Only show particles that deposited energy within a certain range.

- Filter by track shape: Distinguish between circular alpha tracks and more linear beta tracks.

- Filter by coincidence: Only show particle tracks that occurred at the same time as a gamma ray of a specific energy (like the 511 keV gammas from positron annihilation).

Using these filters, we can generate different types of images: simple activity maps (showing where particles hit) or spectroscopic maps (showing where energy was deposited). We can also choose to show the full particle track (“event map”) or just the calculated center point (“centroid”) of the track, which can significantly improve image resolution, especially for alpha particles.

Comparing to What’s Out There

So, how does QPID stack up against other digital autoradiography systems? Pretty well, if we do say so ourselves!

- Older Digital Systems (like CMOS/ZnS(Ag) or PIM): While these were improvements over film, they often have much slower detection times (milliseconds to microseconds) compared to QPID’s nanosecond resolution. This speed difference is critical for coincidence detection.

- Gamma Coincidence: This is a major differentiator. Systems like the iQID (CMOS/ZnS(Ag)) have exposure times too long to effectively tag individual particle events with coincident gamma rays. While PIM systems *could* theoretically do it, it hasn’t been demonstrated. QPID’s synchronized nanosecond timing makes it possible, even if the detection efficiency for coincident events (like beta+ annihilation gammas) is currently modest (around 2.3% for 18F in our tests). We believe future designs can improve this by increasing the coverage of the gamma detector.

- Dual-Isotope Imaging: This is perhaps QPID’s most unique immediate advantage. As we showed with the 223Ra/18F bone study, we can separate the signals from two different radioisotopes in the same sample. This is incredibly difficult or impossible with other systems, especially when one isotope emits alphas (often with beta- daughters) and the other emits beta+ particles. The gamma coincidence tagging is key here to isolate the beta+ signal.

- Microdosimetry Potential: While other systems might offer some spectral information or dose estimation, QPID’s ability to measure energy deposition for *each individual particle track* and identify the particle type provides a much richer dataset for developing accurate microdosimetry models.

Our studies showed that QPID is linear in its response within the typical activity ranges found in tissue samples from animal studies (up to hundreds or even thousands of Bq depending on the isotope). We successfully measured T cell distribution and, importantly, demonstrated the ability to separate and quantify 223Ra and 18F in the same bone sample. We even saw how the bone tissue attenuated the alpha particles from 223Ra, something we could observe by comparing the measured activities to those from a standard dose calibrator and leveraging the simultaneously acquired 18F data as a reference.

The Road Ahead

While we’re thrilled with what QPID can do, this is just the beginning. There’s more work to be done to fully characterize the system’s performance, especially its energy and spatial resolution for different particles. We also need to develop comprehensive computer simulations (Monte Carlo methods) to accurately translate the energy measured in the silicon detector to the actual dose deposited in the tissue sample, accounting for things like tissue density and scattering.

Despite these challenges, the potential is clear. QPID brings together quantitative measurement, spectral analysis, and unique particle identification capabilities, all enabled by the incredible timing resolution of the Timepix3 sensor and our gamma coincidence setup. This allows for much more sophisticated analysis of autoradiography samples than ever before.

Ultimately, we believe QPID is a significant step towards achieving multi-radionuclide microdosimetry in tissue. This means we can get a much better picture of how different radioactive isotopes behave and deliver dose at a very fine scale, which is absolutely critical for developing accurate, personalized dosimetry models for patients receiving radiopharmaceutical therapy. It’s about getting the right dose to the right place, and QPID is helping us see how to do that better.

Source: Springer