Unlocking Life’s Teamwork: Finding Protein Complexes with AI and Gene Ontology

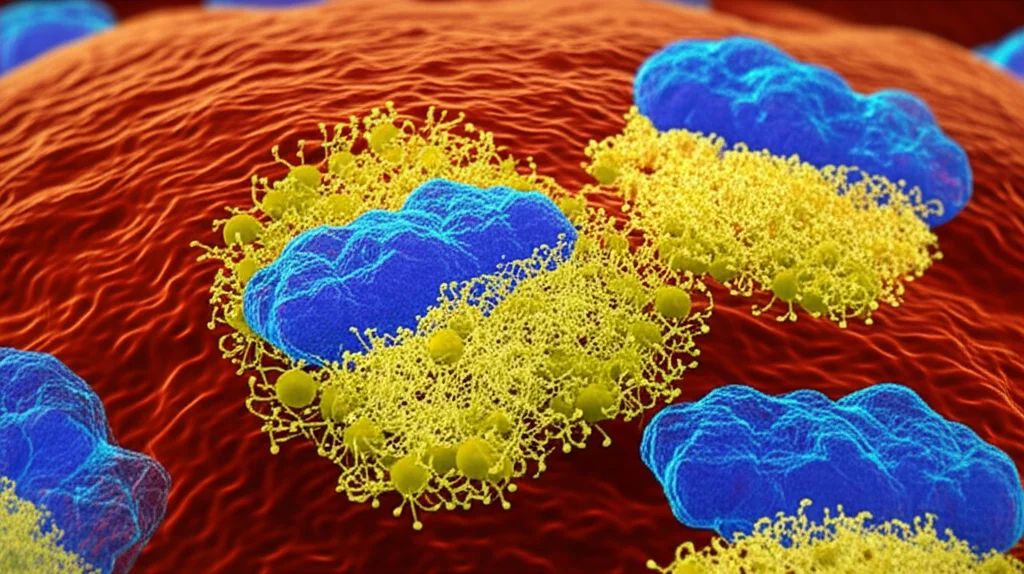

Hey there! Let’s dive into something pretty fascinating happening in the world of biology and computer science. We’re talking about proteins – you know, the workhorses of our cells. They don’t just hang out alone; they team up to form “protein complexes” to get important jobs done. Think of them like tiny biological squads.

Figuring out which proteins belong to which squad, especially within those massive networks of protein-protein interactions (PPIs), is super important. It helps us understand how cells work, what goes wrong in diseases, and even find new drug targets. It’s a big puzzle, and honestly, it’s quite tricky to solve.

The Challenge: Finding the Right Squads

These PPI networks can be huge and messy. Imagine a giant social network, but instead of people, it’s proteins, and connections are interactions. Finding tightly knit groups (the complexes) in such a network is computationally really hard. We’re talking about problems that fall into a category called NP-hard – basically, finding the *absolute* perfect solution takes way too long as the network gets bigger.

Traditionally, folks have used algorithms that look at the network’s structure – how connected things are, how dense certain areas are. These are called topological methods. They’re useful, but they can miss things, especially smaller groups or those with weaker connections. Plus, real-world PPI data often has noise – some connections might be fake, and some real ones might be missing. It’s like trying to find friend groups on a social network where some friendships are misreported or not listed at all.

To tackle this, researchers often turn to clever search strategies called meta-heuristics. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs), inspired by natural selection (think survival of the fittest for potential solutions), are a popular choice. They explore the vast space of possible groupings to find good ones.

Our Big Idea: Bringing in Biological Smarts

Here’s where we thought, “Okay, the network structure is one thing, but what about what these proteins *actually do*?” Proteins in the same complex often work together, meaning they likely share similar functions. This functional information is gold, and it’s captured in something called Gene Ontology (GO).

GO is like a structured dictionary describing what genes and proteins do, where they are in the cell, and what biological processes they’re involved in. It organizes this info into categories (Biological Process, Cellular Component, Molecular Function) and shows relationships between terms like “is a” or “part of” in a graph structure.

Most previous EA approaches for finding protein complexes focused mainly on the network’s shape. What we realized is that integrating GO information directly into the *search process* could make a huge difference. And surprisingly, this hadn’t been explored much before, especially not in a way that handles the inherent conflicts in biological data.

So, we set out to do two main things:

- First, redefine the problem: We framed finding protein complexes as a multi-objective optimization problem. This means instead of trying to optimize just one thing (like network density), we try to optimize several things at once, even if they pull in different directions. In our case, we wanted to balance how functionally similar proteins are *within* a complex versus how functionally similar they are to proteins *outside* that complex. These are naturally conflicting goals – making one group super tight might accidentally make it look similar to another group.

- Second, create a smarter search tool: We developed a brand-new mutation operator for our evolutionary algorithm, which we charmingly named the Functional Similarity-Based Protein Translocation Operator (FS-PTO). This operator uses the GO-based functional similarity between proteins to guide the algorithm. It helps proteins “move” between potential complexes during the search process, nudging them towards groups where their function is a better fit.

Think of the multi-objective part as trying to build several sports teams simultaneously. One objective might be “make sure players on the same team are good at passing to each other” (intra-complex connection/similarity). Another might be “make sure players on different teams aren’t *too* similar in skills, so the teams are distinct” (inter-complex separation). You need to find a balance.

And the FS-PTO operator? That’s like a coach who looks at a player’s specific skills (their GO functions) and says, “You know what, you’d actually be a better fit for *that* team over there,” and moves them. This isn’t random; it’s guided by functional compatibility.

Diving into the Details (Without Getting Lost)

To make this work, we needed a way to quantify functional similarity based on GO. We used methods that look at the relationships between GO terms assigned to different proteins. If two proteins share many GO terms, especially specific ones lower down in the GO graph hierarchy, they’re considered functionally similar. We calculated this similarity between all pairs of proteins in the network.

Our multi-objective model then uses this functional similarity. One objective function aims to maximize the functional coherence *within* each detected complex (Intra-Complex Semantic score). The other objective function aims to minimize the functional similarity *between* different complexes (Inter-Complex Semantic score). By optimizing these two conflicting objectives simultaneously, our evolutionary algorithm explores solutions that represent good trade-offs between internal cohesion and external separation based on function.

The FS-PTO operator specifically looks for proteins that seem like functional outliers in their current complex (their functional similarity to others *outside* the complex is higher than to those *inside*). It then considers moving these “weak” proteins to a different complex where they might fit better functionally. This targeted mutation helps the algorithm refine the complex structures based on biological meaning, not just network links.

Why Biological Data is a Game Changer

Let me give you a quick example from the paper. Imagine two proteins, YBR198C and YMR227C, that are known to be in the same complex according to biological databases, but they don’t have a direct physical interaction link in the PPI network. A purely topological method that only looks at connections would likely *fail* to group them together.

But when we look at their GO annotations, turns out they share quite a few functional terms! Our GO-based approach, especially with the FS-PTO operator, can pick up on this shared function and correctly place them in the same complex, even without a direct link in the interaction network. This is a huge advantage, as it allows us to find biologically relevant complexes that might be missed by methods relying solely on network structure, especially in noisy data.

We tested our algorithm extensively on standard yeast PPI networks (Yeast-D1 and Yeast-D2) and benchmark protein complex datasets (Complex-D1 and Complex-D2). We compared its performance against several state-of-the-art methods, both traditional heuristic ones and other evolutionary algorithms.

Putting it to the Test: Results Speak Volumes

The results were pretty exciting! Our algorithm, MOEA-GOFS-PTO, consistently outperformed the other methods in accurately identifying known protein complexes. We measured success using standard metrics like recall, precision, and F-score, which tell us how well our detected complexes match the known ones (how many true members we found, how many false members we included, and a balance of both).

One particularly important test was evaluating robustness. We deliberately messed up the PPI networks by randomly adding fake interactions or removing real ones to simulate noisy experimental data. Our algorithm held up really well under these conditions, demonstrating its ability to find complexes even when the input network isn’t perfect. This is super important for real-world applications, as biological data is rarely pristine.

The comparison showed that incorporating the GO-based FS-PTO operator made a significant difference. Evolutionary algorithms using our GO-informed mutation found higher quality complexes compared to those relying on purely topological mutations or other standard operators. It really highlights the power of guiding the evolutionary search with biological knowledge.

We even looked at specific examples of known complexes and saw how our method correctly grouped proteins based on shared function, while other methods sometimes included unrelated proteins or missed true members, especially if they lacked direct physical links but shared functional roles.

Wrapping Up

So, what’s the takeaway? We’ve shown that treating protein complex detection as a multi-objective optimization problem and, crucially, integrating functional information from Gene Ontology directly into the evolutionary search process – both in the objectives and through our novel FS-PTO mutation operator – leads to a more powerful and accurate approach.

This work really underscores the potential of combining sophisticated computational techniques like evolutionary algorithms with rich biological data sources like GO. It’s a step forward in our ability to automatically uncover the functional teams of proteins that keep our cells running.

Of course, there’s always more to explore! Future work could look at even more complex scenarios, like complexes that overlap (where a protein belongs to more than one team) or complexes of vastly different sizes. But for now, we’re pretty excited about what this GO-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm can do!

Source: Springer