Holey Titanium for Better Bones: Unpacking Porosity e Strength

Hey there! Ever thought about what goes into fixing a broken bone or replacing a worn-out joint? It’s pretty amazing stuff, right? For a long time, materials like stainless steel and cobalt-chromium alloys were the go-to, but titanium alloys have really stolen the show lately. Why? Because they’re tough, they don’t corrode easily, and our bodies generally get along with them. Basically, they’re biocompatible superheroes!

But here’s a little snag: solid titanium is *really* stiff. Like, way stiffer than your actual bones. Your bone has a Young’s modulus (fancy word for stiffness) of about 10-30 GPa, while solid titanium is up there at 103–120 GPa. Sticking something *that* stiff next to bone can cause problems with how the bone remodels and heals over time. Not ideal.

So, smart folks figured, “Okay, if it’s too stiff, let’s make it less stiff!” How do you do that? You add holes! Making titanium porous reduces its stiffness, bringing it closer to that sweet spot of human bone. Ta-da! Porous titanium to the rescue!

The Porosity Predicament: Strength vs. Rust

Now, adding holes sounds simple, but it creates a bit of a balancing act. Think about it: a solid block is stronger than a block with holes, right? Pores inherently weaken the material. Plus, those holes can give corrosive stuff more places to hide and do damage. So, you’ve got this challenge: make it porous enough to be bone-like in stiffness, but keep it strong enough to do its job and resistant enough not to corrode inside the body.

Scientists have been trying all sorts of ways to make porous titanium just right. Some studies, like one by Makena et al., found that more porosity led to *more* corrosion. Their corrosion rates went up significantly as the material got holier. They thought maybe the protective layer on titanium wasn’t working as well with all those pores.

But then, other studies, like one by Dabrowski et al., saw the *opposite*! They found that *higher* porosity sometimes meant *less* corrosion. Their theory? Highly porous structures might be more ‘water-hating’ (hydrophobic) because of tiny gas bubbles trapped in the pores, shielding the surface from corrosive ions. See? Science can be tricky, with different results popping up! Surface wettability – whether water spreads out or beads up – seems to be a big deal here.

And when it comes to strength, the story is clearer. More pores generally mean less strength and lower stiffness. It’s been shown that increasing porosity dramatically drops the compressive strength and elastic modulus. Makes sense – less material to bear the load!

But it’s not just *how many* holes, it’s also about *how big* they are. Some research suggests that pore size also affects mechanical properties. Generally, larger pores seem to lead to lower compressive strength. Wang et al. found that increasing pore size reduced the elastic modulus, and samples with smaller pores were stronger. Zhao et al. thought this might be because smaller pores mean the solid bits between them are stronger and there are fewer spots for stress to concentrate and cause failure.

So, the big question is: how do porosity *and* pore size *together* influence both the strength and the corrosion resistance? That’s exactly what *this* study decided to dive into, methodically investigating these effects on titanium foam.

Making the “Holey” Stuff: A Peek Behind the Curtain

How did they make these special porous titanium samples? They used a technique called the “space holder” method combined with Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS). It sounds fancy, but the core idea is pretty clever.

1. They started with commercially pure titanium powder.

2. They mixed this titanium powder with granules of ordinary salt (NaCl). The salt acts as the “space holder” – it takes up space where they want the pores to be.

3. They varied the *amount* of salt they added (from 0% up to 80% by volume) to control the *porosity* (how many holes).

4. They also used salt particles of different *sizes* (from 100 to 600 μm) to control the *pore size*.

5. They compacted this mix and heated it up using Spark Plasma Sintering. This process rapidly sinters (fuses) the titanium powder particles together around the salt grains.

6. After the sintering, they dissolved the salt away in water, leaving behind the porous titanium structure.

7. They even did a follow-up heat treatment in an argon furnace to make the pore walls stronger.

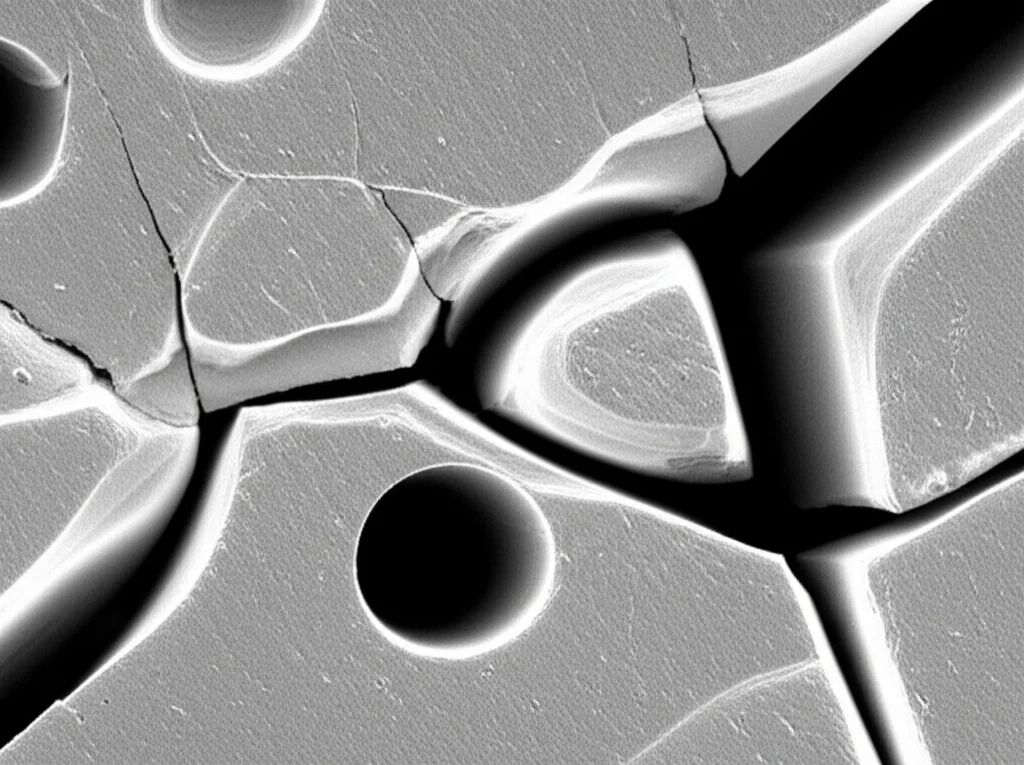

To make sure they knew exactly what they had created, they used microscopes (optical and scanning electron) to look at the structure and, super cool, 3D X-ray micro-CT scanning to get a detailed look at the pores, their sizes, and how well they were connected.

Seeing the Holes: What the Scans Showed

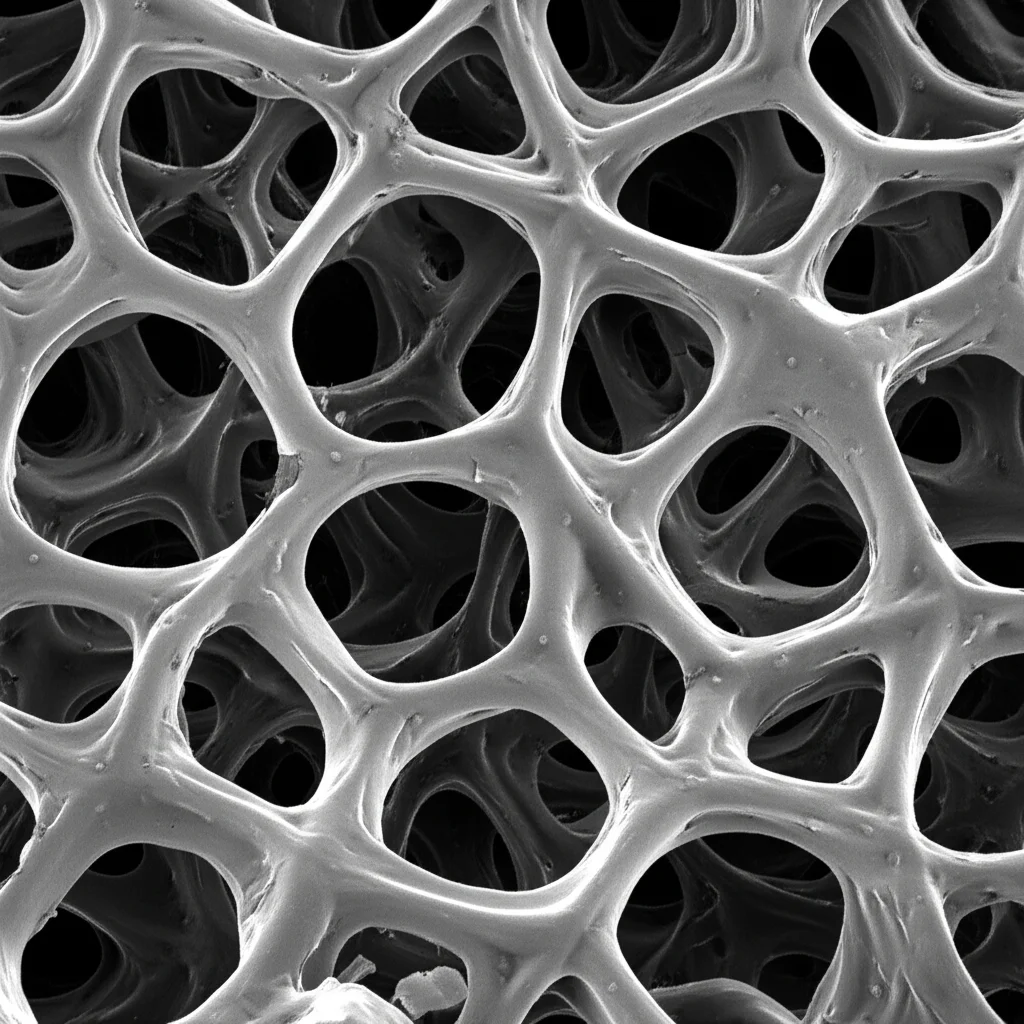

Looking at the samples under a microscope after the salt was gone, you could clearly see the pores. There were the big pores left by the salt particles (macro-pores) and smaller ones between the packed titanium powder particles (micro-pores). As you’d expect, the more salt they started with, the more porous the final material was. The macro-pores even looked like the cuboidal shape of the original salt granules!

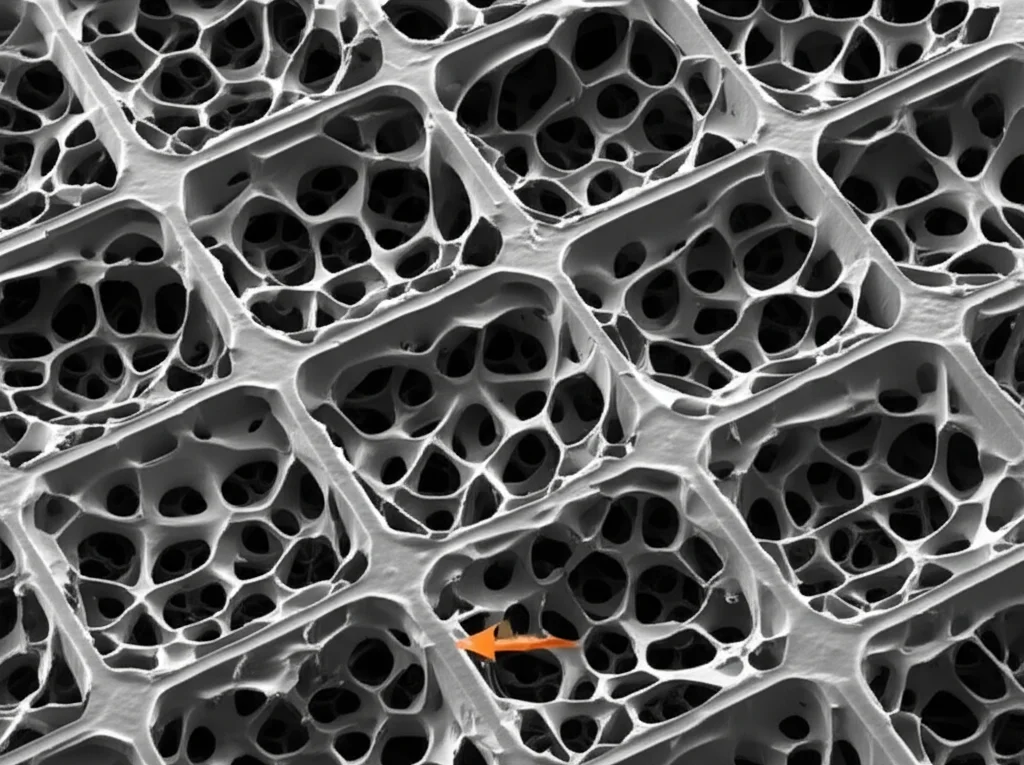

The 3D X-ray scans were key for understanding how the pores linked up. They used colors – blue for isolated/closed pores and red for open and connected ones. What they saw was that as they increased the overall porosity (more salt), the pores became more interconnected. This makes sense; with more holes, there’s a higher chance they’ll bump into each other and link up.

Here’s where it gets interesting regarding pore *size*: the samples made with *smaller* salt particles actually showed *better* pore interconnectivity than those made with larger particles. Why? They figure it’s because to get the same volume of pores, you need way more small particles than large ones, and these smaller particles have a higher total surface area, leading to more contact points between them, and thus, more connections after sintering.

The Corrosion Story: Small Pores Win?

Next up was the corrosion test. They put the samples in a salty solution (similar to body fluid) and measured how they reacted over time.

They looked at the open-circuit potential (OCP) first. This tells you how the material’s surface is stabilizing in the environment. All samples seemed to form a protective layer. Interestingly, samples with *smaller* pores stabilized at more positive potentials, which usually suggests better corrosion resistance.

Then came the potentiodynamic polarization curves, which give you more detailed info, like the corrosion rate. The big finding here was that the sample with the *finest* pores (100–212 μm) had the lowest passive current and the lowest corrosion rate. So, in this study, smaller pores meant better corrosion resistance.

Why did the smaller pores perform better? They attributed it largely to that increased pore interconnectivity they saw in the CT scans. Well-connected pores allow the fluid (the salty solution) to flow more freely. This prevents stagnant areas where corrosive ions can build up, reducing the risk of crevice corrosion. They also mentioned the idea of hydrophobicity again – maybe the smaller, more connected pores somehow make the surface less ‘attractive’ to the corrosive solution. It’s a complex interplay!

The Strength Test: Holes Make it Weaker (But How Much?)

Time to see how strong this porous titanium is. They put samples under compression to see how much load they could handle before deforming or breaking.

As everyone expected, adding pores reduced the strength. The dense titanium (0% porosity) was the strongest and stiffest, naturally. As the porosity increased, the compressive strength and elastic modulus dropped significantly. It was almost a linear relationship – double the holes, roughly half the strength (or even less). This is because the pores act like defects and stress concentrators. More holes mean more weak spots and thinner walls between the pores.

But what about pore *size*? Here, they found that compressive strength *decreased* as the pore size *increased*. The samples with the largest pores (425–600 μm) were weaker than those with medium or small pores. The samples with the smallest pores (100–212 μm) were the strongest among the porous ones.

Why would bigger pores mean less strength? They suggested it’s related to the surface area of the pores. Smaller pores, for the same volume, have a higher total surface area, but perhaps the solid struts between them are thicker and more robust, providing better support. Also, they mentioned that smaller salt particles might tend to clump together during fabrication, potentially creating larger, weaker agglomerated pores. Samples with larger pores might have more continuous, dense solid areas supporting the load.

They also watched *how* the samples failed under compression. At lower porosities (like 40% or 60%), the samples tended to fail by shearing – essentially sliding along diagonal lines. But at very high porosity (80%), the failure mode shifted to “barrelling,” where the sample bulged outwards in the middle. This happens when the material isn’t strong enough to resist the crack propagation in the loading direction, so it just expands sideways instead.

Bringing It All Together: Bone-Like Potential?

So, what’s the big picture from this study?

* They successfully made porous titanium using a neat technique, controlling both the amount of porosity and the size of the pores.

* Pore interconnectivity is key, increasing with overall porosity but surprisingly *decreasing* with larger pore sizes.

* When it comes to corrosion in a body-like environment, *smaller* pores seem to offer better resistance, likely thanks to better interconnectivity and maybe some surface effects.

* For strength, it’s a trade-off: more pores mean less strength (linearly), and *larger* pores also mean less strength compared to smaller ones.

* The way the material breaks under pressure changes depending on how porous it is.

The really exciting part? The strength and stiffness values they got for their porous titanium samples actually fall within the range of human bone – both the dense outer bone (compact) and the spongy inner bone (cancellous). Their samples ranged from about 11 to 160 MPa in compressive strength and 0.61 to 18.70 GPa in elastic modulus, which lines up nicely with bone properties (2-180 MPa strength, <3 GPa for cancellous, 12-17 GPa for compact).

This means these porous titanium materials have serious potential for use in medical implants! Getting the mechanical properties right is a huge step.

Of course, science never stops! The researchers mentioned that future work could involve adding other biocompatible elements (like Niobium, Molybdenum, and Tin) to the mix to see if they can tweak the properties even more. And, crucially, they need to do *in vivo* tests – seeing how these materials perform inside a living body, including how well bone grows into the pores (bone formation mechanisms).

It's a complex puzzle, balancing strength, corrosion, and bone compatibility, but studies like this are getting us closer to making implant materials that are truly integrated with our bodies. Pretty cool, huh?

Source: Springer