Tiny Plastics, Big Lung Trouble? What Microplastics Do to Your Airways

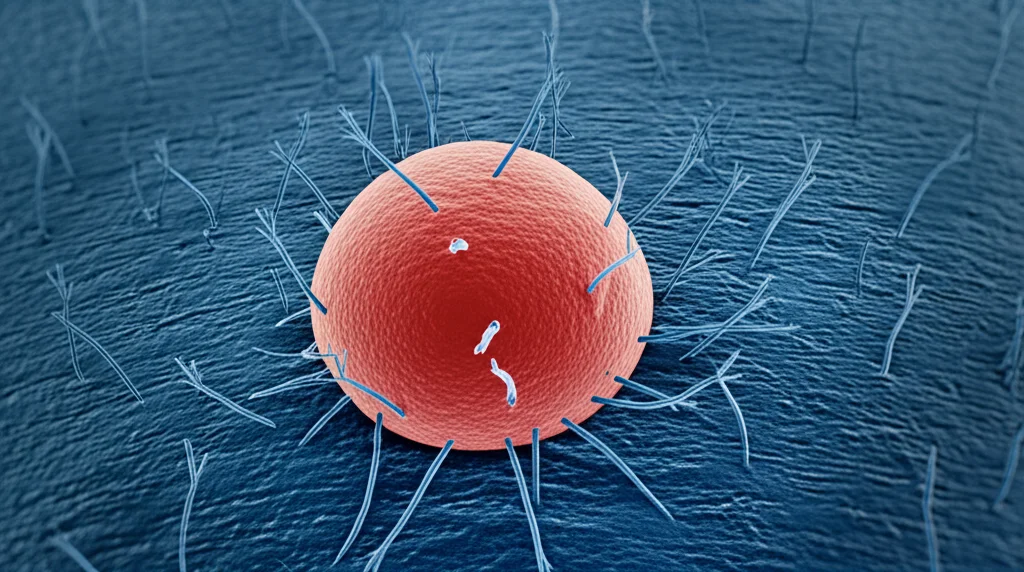

Hey there! Let’s talk about something that’s literally in the air we breathe – tiny plastic bits. You know, microplastics and nanoplastics (let’s just call them MNPs for short). We hear a lot about eating them, but what about inhaling them? Turns out, that’s a pretty big deal too, and honestly, we haven’t known *that* much about how these airborne invaders mess with our lungs, especially the cells lining our airways.

Most of the studies out there have been using these perfectly round, lab-made polystyrene (PS) particles in super high doses. But let’s be real, the plastic floating around in our environment isn’t usually like that. It’s often amorphous, meaning it has irregular shapes, and it comes from all sorts of stuff – tires, textiles, industrial bits, you name it. And it’s made of different polymers like PVC, PP, and PA. So, we needed to figure out what *these* kinds of environmentally relevant MNPs actually do to our cells.

What We Set Out to Discover

So, the brilliant minds behind this study (and hey, I’m just here to chat about it!) decided to dive deep. They wanted to see the potential toxicity of these real-world MNPs – specifically from Polyvinylchloride (PVC), Polypropylene (PP), and Polyamide (PA). They also looked at different sizes, from the super-tiny nanoplastics (less than 1 micrometer) all the way up to microplastics (1-10 micrometers). And get this, they even checked out the chemicals that leach out of these plastics, just in case the problem wasn’t the particle itself, but the stuff coming off it.

They used human bronchial epithelial cells (the kind that line your airways, called BEAS-2B cells in the lab) and exposed them to different doses of these MNPs. Then, they watched for signs of trouble:

- Cytotoxicity: Were the cells dying?

- Inflammation: Were the cells getting angry and releasing inflammatory signals like IL-8?

- Oxidative Stress: Were the cells getting stressed out at a molecular level?

They even peeked into *how* inflammation might be happening by looking at some key cellular switches called NF-κB and AP-1.

The Big Reveal: Not All Plastics Are Created Equal

Okay, so what did they find? This is where it gets interesting. It turns out, the type of plastic *and* its size really, really matter.

Guess which one was the bad guy? Polyamide, or PA, especially the *nano*plastics (< 1 µm). These tiny PA particles were the only ones that caused significant cell death. Ouch. They also triggered a big inflammatory response, making the cells pump out IL-8 and turn on inflammatory genes.

What about the others? PVC particles, no matter the size or dose, didn't seem to cause much trouble in these cells. PP/Talc particles (remember, PP often has talc added) did cause some increased IL-8 secretion, but the researchers suspect a lot of that might actually be due to the talc filler, not just the PP itself.

And those leachates? The chemicals coming off the plastics? In this study, they didn't seem to cause any cytotoxicity or inflammation. So, at least in this setup, the particle itself seemed to be the main issue.

Diving Deeper into the PA Problem

Since PA nanoplastics were the main culprits, the researchers dug a bit deeper into *how* they were causing inflammation. They found that PA nanoplastics activated the NF-κB pathway, which is a major switch for turning on inflammatory responses in cells. Interestingly, another pathway called AP-1 wasn’t affected by PA.

They also looked at oxidative stress. While PA didn’t directly increase general reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels (the stuff that causes oxidative damage), it *did* increase the expression of a specific antioxidant gene called *SOD2*. This gene is actually linked to the NF-κB pathway, suggesting a complex interplay. And get this – when they used an antioxidant (quercetin), it reduced the PA-induced inflammation, hinting that oxidative stress *does* play a role in triggering that NF-κB switch, even if they didn’t see a direct ROS increase with their method (which they admit might have been affected by the particles themselves).

Why Size Matters (Especially When It’s Nano)

The study really highlighted that nanoplastics, particularly PA nanoplastics, were more toxic than their microplastic counterparts. Why? Well, smaller particles can potentially get deeper into the lungs. Plus, nanoplastics have a much larger surface area compared to their mass than microplastics do. Think about it: a tiny particle has proportionally more “outside” to interact with cells than a bigger one. This larger surface area means more potential contact points, more chances for interaction with cell membranes, and possibly higher uptake into the cells. The researchers even calculated that when you look at the *number* of particles delivered to the cells, the nanoplastics dose was higher than the microplastics dose for the same mass, which could also explain the difference in effects.

This lines up with other studies that have shown smaller PS nanoplastics are more toxic to lung cells than larger PS microplastics.

Comparing Apples and Oranges (or PVC, PP, and PA)

Finding environmentally relevant MNPs to study is actually pretty tricky! Most commercially available ones are spherical PS. This study used amorphous particles from polymers commonly found in indoor air and even human lung tissue (PP and PET are the most prevalent there, with PS being less common).

* PVC: In this study, PVC didn’t cause cytotoxicity. Another study using higher doses *did* see effects, so maybe it depends on the dose and specific particle characteristics.

* PP/Talc: As mentioned, the IL-8 increase might be from the talc filler. Talc itself is a bit controversial and has been reclassified as potentially carcinogenic by some agencies. Other studies *have* shown PP nanoplastics causing issues like mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation in different lung cells (A549), but those studies didn’t include talc. It’s complicated!

* PA: This study found PA to be the most toxic, causing both cell death and inflammation. This aligns with some older studies looking at dust from PA production plants causing inflammation in animals. However, other studies on PA fibers or particles in animals didn’t see inflammation, and one study on A549 cells didn’t see cytotoxicity with PA nanoplastics. This highlights that cell type, exposure method, and even the specific type of PA might lead to different results.

Challenges and What’s Next

Studying these tiny particles in a lab isn’t without its challenges. Getting the dose right is tricky because particles can agglomerate (clump together) in the cell culture medium, and how much actually reaches the cells depends on their density and size distribution. The researchers used a fancy model to estimate the *delivered* dose, which is super important.

Also, this study looked at *acute* exposure (just 24 hours). In the real world, we’re exposed to MNPs constantly over our lifetime, and they can accumulate in the lungs. This study used a cell line grown in a dish under liquid, which isn’t exactly like the complex environment of a real lung with air and different cell types interacting. While this setup is great for screening lots of conditions, future research needs to use more advanced models or even animal studies to get a better picture.

Plus, the real MNPs out there aren’t just fresh plastic; they’re weathered by UV light and potentially broken down by microbes, which can change their properties and maybe their toxicity. That’s another area for future research.

Wrapping It Up

So, what’s the takeaway from all this? My friends, this study is a really important step because it looked at environmentally relevant, amorphous MNPs, not just the standard lab-made ones. It tells us loud and clear that the toxicity of these tiny plastic bits to our bronchial cells isn’t a one-size-fits-all situation. It depends heavily on the *type* of plastic, the *size* of the particle (nanoplastics seem more potent), and the *dose*. PA nanoplastics, in particular, raised a red flag by causing cell death and inflammation via that NF-κB pathway.

This kind of research is crucial for understanding the potential health risks of the plastic pollution that’s now part of our air. It helps inform regulatory bodies and public health efforts. There’s still a lot to learn, but studies like this are shining a much-needed light on the hidden dangers of tiny plastics in our lungs.

Source: Springer