Unlocking aHUS Diagnosis: How the PLASMIC Score Can Help

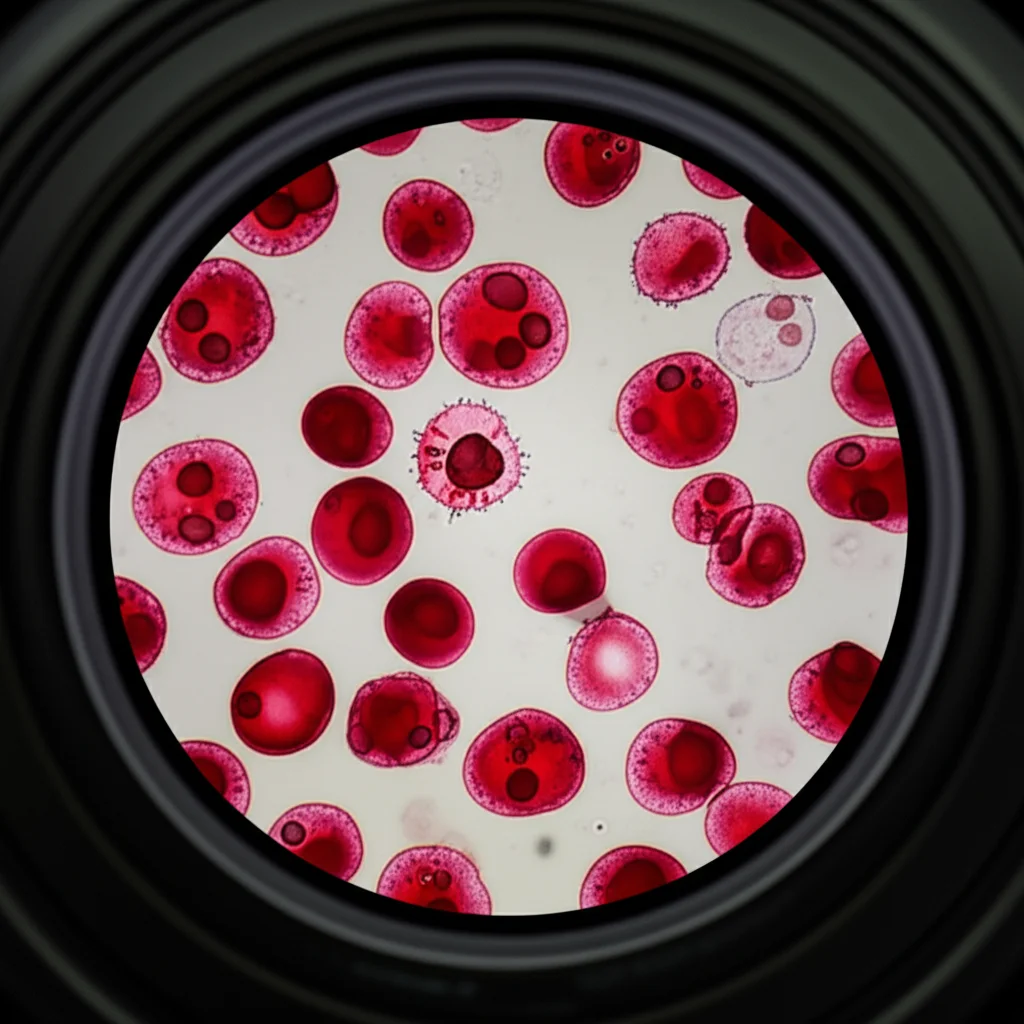

Hey there! Let’s chat about something pretty important in the medical world, specifically when it comes to diagnosing a tricky condition called atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, or aHUS for short. Now, aHUS is a type of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), which sounds complicated, I know, but basically, it messes with your small blood vessels and can cause serious damage to organs, especially the kidneys. Without the right treatment, it can be really dangerous.

The big challenge? TMAs can look a lot alike! There’s aHUS, and then there’s thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and also STEC-HUS (which is linked to a specific type of E. coli). They might show up with similar symptoms like low platelets and damaged red blood cells, but their root causes and, crucially, their treatments are different. Getting it wrong or being slow can have serious consequences for the patient.

The Diagnostic Dilemma

Think of it like trying to tell two very similar cars apart in a hurry – they both have wheels and an engine, but one needs diesel and the other needs petrol, and giving the wrong one the wrong fuel is a disaster! For TTP, the key is a severe deficiency in something called ADAMTS13 activity (less than 10%). For aHUS, ADAMTS13 levels are usually normal (10% or higher). And while plasma exchange (PE) is a go-to for TTP, it doesn’t work well for aHUS.

The problem is, testing for ADAMTS13 activity isn’t always quick or easily available. It can take days to get results back in many places. This delay means doctors might not be sure what they’re dealing with right away, and that can hold up the specific treatment needed, like starting medications that target the complement system, which is often out of whack in aHUS. Delayed treatment can lead to dialysis, kidney failure, and worse. So, finding a way to get a clearer picture faster is a really big deal.

Enter the PLASMIC Score

This is where the PLASMIC Score comes into the picture. It was actually developed to help doctors figure out the likelihood of severe ADAMTS13 deficiency – essentially, to help diagnose TTP quickly. It uses seven simple things you can usually find from lab tests and a patient’s history. Each factor gets a point, and the total score ranges from 0 to 7. A high score, like 6 or 7, strongly suggests severe ADAMTS13 deficiency, pointing towards TTP.

But what about aHUS? Could this score, designed for TTP, also help us identify aHUS? That was the big question we wanted to explore in this study. We figured if the score is good at flagging TTP (high score), maybe lower scores could help rule it out and point towards other TMAs like aHUS.

How We Looked Under the Hood

To get some answers, we looked at data from a couple of places. First, we analyzed data from clinical trials for two medications used to treat aHUS: eculizumab and ravulizumab. These trials included patients who were already diagnosed with aHUS, so they gave us a group of people we *knew* had the condition. We calculated their PLASMIC scores based on the trial data. Importantly, patients with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (TTP) were excluded from these trials, so this dataset was a solid representation of aHUS patients.

Second, we dove into a massive real-world database called the PINC AI™ Healthcare Database (PHD). This database contains information from lots of US hospitals. We looked for patients who had a TMA diagnosis and had their ADAMTS13 activity tested. We set up specific criteria to try and identify patients in this real-world setting who likely had aHUS (TMA diagnosis, no STEC-HUS, and ADAMTS13 activity 10% or higher) versus those who likely had TTP (TMA diagnosis, no STEC-HUS, and ADAMTS13 activity less than 10%). We calculated PLASMIC scores for these patients too and then checked how well the score helped distinguish between probable aHUS and TTP. We focused on patients with kidney problems (renal impairment) in our main analysis, as this is common in aHUS, and also did some checks on slightly different groups to make sure our findings were consistent.

What the Scores Showed

Looking at the clinical trial data from the 94 known aHUS patients, we found something interesting. The majority of these patients had relatively low PLASMIC scores. In both the eculizumab and ravulizumab trials, about half the patients scored a 4. And overall, around 85% of the aHUS patients in these trials had a PLASMIC score of 5 or less. Their scores typically ranged from 3 to 5. Only a small number (about 13%) had a score of 6 or higher. This tells us that if someone has aHUS, they’re *unlikely* to have a high PLASMIC score.

Now, for the real-world data from the PHD database, we had 110 patients in our main group who had TMA, kidney issues, and ADAMTS13 results. When we looked at how well the PLASMIC score could identify probable aHUS (defined by ADAMTS13 >= 10%), we found that using a cutoff score of 5 or less worked pretty well.

* If a patient scored 5 or less, there was a good chance they had probable aHUS (this is called positive predictive value, or PPV, which was 92.8% at this cutoff).

* The test was also good at catching most of the probable aHUS cases (sensitivity was 86.5%).

* It wasn’t quite as good at ruling out TTP (specificity was 71.4%), meaning some TTP patients might still score 5 or less.

* However, if you scored *above* 5 (i.e., 6 or 7), it was pretty good at telling you that you *didn’t* have probable aHUS (negative predictive value, or NPV, was 55.6% at this cutoff, but let’s look at the TTP side too).

We also looked at a cutoff of 4 or less. This was less sensitive for finding *all* probable aHUS cases (only 62.9% sensitivity), but it was much better at ruling out TTP. If you scored 4 or less, it was highly unlikely you had TTP (NPV was 85.7%), with very few TTP patients falling into this low score group. This suggests that a low score, especially 4 or less, is a strong indicator *against* TTP, which indirectly supports an aHUS diagnosis if other TMAs are ruled out. The analysis showed that a score of 5 or less is where probable aHUS patients tend to fall.

Connecting the Dots

So, what does this all mean? It seems like the PLASMIC Score, even though it was designed to find TTP, can be a really useful tool in the diagnostic process for aHUS too. If a patient shows up with TMA symptoms and their PLASMIC score is low, particularly 5 or less (and even more so 4 or less), it makes TTP much less likely. Since aHUS is often diagnosed by ruling out other TMAs like TTP and STEC-HUS, a low PLASMIC score can give doctors more confidence that they might be dealing with aHUS relatively early on.

This is super important because, as we mentioned, getting the right diagnosis quickly means starting the right treatment sooner. Earlier treatment for aHUS, especially with targeted therapies, has been linked to better outcomes, like not needing dialysis as much and better kidney recovery.

Not a Solo Act

Now, it’s crucial to remember that the PLASMIC Score isn’t a magic bullet or a replacement for a doctor’s clinical judgment. It’s a tool to *support* the diagnosis. Doctors still need to consider the whole clinical picture, rule out other conditions that can mimic TMA (like certain cancers or DIC), and ideally, get that ADAMTS13 test done, even if it takes a few days. The score helps prioritize and act while waiting for definitive results.

Our findings line up with other studies that have shown the PLASMIC score is great at predicting or ruling out severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (TTP). The fact that we saw similar results in both controlled clinical trials and messy real-world data strengthens the case for using the PLASMIC score in this way.

We did notice that two specific components of the PLASMIC score – the platelet count threshold (elt;30 x 10^9/L) and the creatinine threshold (elt;2.0 mg/dL) – were met by fewer patients in the aHUS groups compared to what you might expect in TTP. This might mean those specific thresholds are more geared towards TTP, and maybe future studies could look at how individual components perform in aHUS. Also, we should keep in mind that the PLASMIC score’s accuracy for TTP might be lower in older patients (over 40), though our study’s median age was higher, and this effect hasn’t been noted for aHUS. It’s just something for clinicians to consider.

The Bottom Line

One of the biggest frustrations for doctors diagnosing aHUS is the delay in getting lab results and the lack of a single definitive test. The PLASMIC score, with its reliance on commonly available lab values, could really help streamline the process, especially in places where advanced testing isn’t readily available.

Of course, this study had its limitations. It was retrospective, meaning we looked back at existing data, which can have issues with how information was recorded. There wasn’t a specific diagnostic code for aHUS in the database during the study period, which made identifying probable cases a bit more complex. We also couldn’t track patients across different hospitals. And since we only looked at patients already diagnosed with TMA, we can’t say how the PLASMIC score would perform in patients with TMA-like symptoms but who don’t end up having TMA.

Despite these points, the overall message is clear: if you have a patient with confirmed TMA and kidney problems, and their PLASMIC score is 5 or less (especially 3-5), it strongly suggests that aHUS is the likely culprit, and TTP is less likely. Adding the PLASMIC score to the diagnostic toolkit won’t replace clinical expertise, but it can definitely boost confidence in an early aHUS diagnosis, paving the way for faster, more effective treatment and hopefully, much better outcomes for patients. It’s another piece of the puzzle falling into place!

Source: Springer