Picric Acid vs. Rapeseed: Unraveling a Mutagenic Mystery

Hey there! So, I’ve been digging into some fascinating science lately, specifically about how certain chemicals can mess with our favorite plants. Today, I want to chat about something called picric acid and its rather dramatic impact on a super important crop: rapeseed, or what many of us know as canola (*Brassica napus*).

You see, *Brassica napus* is a big deal globally. It’s this bright yellow beauty that gives us tons of vegetable oil and is a key player in biofuels. Plus, it’s a major source of protein. But, like many crops, it’s facing tough times with climate change. Droughts and heat waves can really hit its yield hard. This is where the need for stronger, more adaptable varieties comes in.

Traditionally, plant breeders have crossed different varieties to get the best traits. But sometimes, you need a faster way to introduce new variations. Enter mutation breeding! It’s a technique where scientists intentionally cause changes (mutations) in a plant’s DNA to hopefully stumble upon something useful – maybe higher yield, better oil quality, or resistance to pests and tough weather. They’ve been doing this for decades, using things like X-rays or chemicals.

What’s Picric Acid Anyway?

Now, the chemical we’re focusing on here is picric acid. Sounds a bit… well, *acidic*, right? Its proper name is 2,4,6-trinitrophenol, and it’s known for being quite bitter (hence the name, from the Greek “pikros”). It’s a stable molecule, but when it gets into cells, it can interact with DNA and cause changes. Scientists have suspected its mutagenic potential for a while, but its effects on rapeseed, especially at the genetic level, weren’t fully clear.

Setting Up the Experiment

So, a group of researchers decided to dive deep and see exactly what picric acid does to *Brassica napus*. They set up a pretty neat experiment out in the field. They took seeds from three different rapeseed varieties – Abasin-95, Dur e Nifa, and Nifa Gold – and gave them a little bath in picric acid solutions. They tested five different concentrations (from 0 mM, which was the control, up to 20 mM) and three different soaking times (3, 6, and 9 hours).

After their picric acid spa treatment (followed by a good rinse!), the seeds were planted. The scientists then meticulously tracked all sorts of things as the plants grew:

- How long it took for seedlings to pop up (emergence).

- How long it took for germination to be complete.

- The percentage of seeds that actually emerged.

- The number and size of leaves.

- The plant’s height.

- The number and weight of the seed pods (siliqua).

- The weight of the seeds themselves.

- The moisture content of the plants.

- And, crucially, they took samples to look at the DNA, specifically the chloroplast genome.

They compared all these measurements between the treated plants and the untreated control plants to see what was different.

The Early Days: A Bit of a Struggle

Turns out, picric acid wasn’t exactly a gentle start for the seeds. The higher doses, especially the 20 mM one, really put the brakes on seedling emergence. Plants from these seeds took longer to pop out of the soil compared to the control or lower doses. The soaking time also mattered; longer soaking times (3h vs 6h vs 9h) showed significant differences in emergence speed.

Germination time was also affected. The untreated seeds germinated fastest. While lower doses (0, 5, 10 mM) didn’t show huge differences, the 20 mM dose took the longest. Interestingly, among the cultivars, Abasin-95 was the speediest germinator, while Nifa Gold took its sweet time.

And when it came to the *percentage* of seeds that actually emerged? Picric acid caused a noticeable drop. The control group had the highest emergence rate (over 94%), while the 20 mM dose saw a significant dip (down to 76%). It seems picric acid can damage the seed embryo or mess with the enzymes needed for germination, creating stress that might even lead to dormancy. Many other studies with different mutagens have seen similar negative effects on germination, though some have reported the opposite!

Growing Up: Some Surprises!

Now, things got a bit more interesting as the plants grew. While picric acid seemed to hinder the very start, its effects on later growth traits weren’t always negative.

Leaf number was a bit mixed. The highest dose (20 mM) actually resulted in slightly *more* leaves than the control, though the difference wasn’t statistically significant. However, a 10 mM dose seemed to reduce leaf number compared to the control. Soaking time also played a role, with 6 hours being the most favorable for more leaves. The Dur e Nifa cultivar consistently produced the most leaves. The researchers think the reduction in leaves at some doses might be because the mutagen damages the cells responsible for growth, affecting cell division.

Leaf size, on the other hand, saw some improvement, especially with priming (soaking). Seeds soaked for 3 hours produced plants with the largest leaves. The Nifa Gold cultivar showed a significant increase in leaf size compared to the others. This suggests that pre-treating the seeds might help the plants develop defenses or mechanisms to cope with the chemical, leading to bigger leaves – which, of course, are crucial for photosynthesis!

Plant height was another area where picric acid showed a stimulatory effect at certain levels. Doses of 5 mM, 10 mM, 15 mM, and 20 mM all resulted in taller plants than the control group (0 mM). Soaking for 6 hours also led to significantly taller plants. And the Nifa Gold cultivar? It absolutely soared, showing the greatest height among the three. This positive effect on height might be linked to how picric acid interacts with plant growth hormones or stimulates cell division in the stem. Some scientists even hypothesize it could increase the number of stomata (those little pores on leaves), boosting photosynthesis and providing more resources for growth.

When it came to the number of siliqua (the pods where the seeds develop), the effect of picric acid doses wasn’t statistically significant overall. However, the Nifa Gold cultivar again stood out, producing the highest number of pods. This suggests Nifa Gold is quite adaptable to picric acid exposure when it comes to setting fruit.

Seed weight per siliqua didn’t show a significant response to the different picric acid doses either. Abasin-95 had the highest seed weight, though it wasn’t significantly different from Nifa Gold. Dur e Nifa, however, saw a significant decrease in seed weight. This indicates that the genes controlling seed production might be less affected by picric acid, or perhaps the plants have mechanisms to counteract its effects in this area.

Fresh and dry biomass (basically, the total weight of the plant) didn’t show significant changes with picric acid dose, but priming for 6 hours did increase fresh weight. The Dur e Nifa and Nifa Gold cultivars generally had higher biomass than Abasin-95.

Moisture content was a bit complex, varying significantly with dose and cultivar. Higher doses (10 mM and 15 mM) sometimes increased moisture content compared to the control or other doses. The Abasin-95 cultivar had the highest moisture content. This increase in moisture might be due to the mutagen inducing changes like an increase in trichomes (tiny hairs on the plant surface) or stomata, which help the plant conserve water.

The Genetic Fingerprint: Clear Mutations

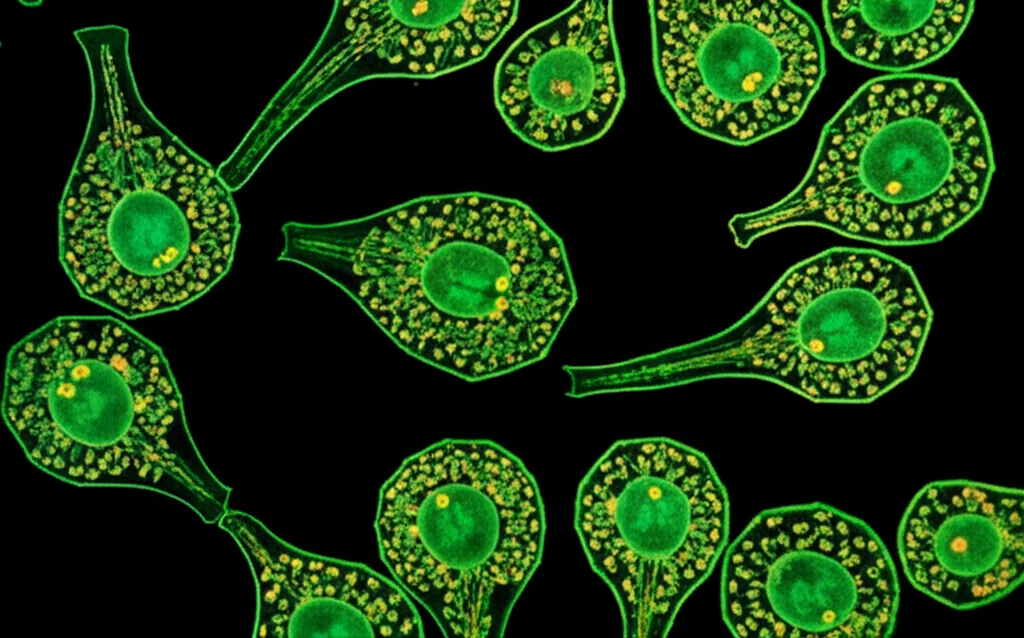

Okay, now for the really technical bit, but stick with me because it’s super cool. The researchers didn’t just look at how the plants *looked* and *grew*. They also peered into their DNA, specifically the chloroplast genome. Chloroplasts are like the plant’s tiny solar panels, where photosynthesis happens. Their DNA is separate from the main DNA in the plant’s nucleus.

They compared the chloroplast DNA from the untreated control plants to the plants grown from picric acid-treated seeds. And guess what? The chloroplast genome of the treated plants was definitely mutated! In fact, it was so changed that the scientists couldn’t even properly “annotate” it – which is like labeling all the genes and features on the DNA map.

They found a whopping 187 single nucleotide substitutions. Imagine the DNA sequence as a long string of letters (A, T, C, G). A single nucleotide substitution is like changing one letter to another (e.g., A becomes T). They also found 43 additions or deletions, where chunks of DNA were either added or removed.

This genomic evidence is pretty solid proof that picric acid is indeed a mutagen for the rapeseed chloroplast genome.

So, What Does It All Mean?

This study gives us a lot to think about. On one hand, picric acid, especially at higher doses, can be detrimental to the early stages of rapeseed growth, slowing down emergence and reducing the number of seeds that sprout. It clearly causes significant mutations in the chloroplast DNA.

On the other hand, the study also showed that certain doses and soaking times could actually *stimulate* later growth traits like plant height and potentially seed weight. And some cultivars, like Nifa Gold, seemed more resilient and productive even under picric acid exposure.

This dual effect – inhibitory early on, potentially stimulatory later – is fascinating. It suggests that while picric acid is a mutagen, its application might need careful tuning depending on what trait you’re trying to influence. It highlights its potential use in mutation breeding programs, but also raises questions about the environmental impact if this chemical were to get into agricultural systems.

The researchers suggest future studies could look into:

- Whether these picric acid-induced mutations make the plants more or less resistant to stress (heat, salt, drought).

- If these mutations could be used to create new rapeseed varieties with desirable traits.

- How picric acid affects other important plant compounds (secondary metabolites).

- The potential environmental risks of picric acid to other organisms.

- Combining this knowledge with gene-editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9.

Overall, this research confirms that picric acid is a potent mutagen for rapeseed, significantly altering its chloroplast genome and influencing various biological traits. It’s a complex interaction, showing both negative effects on early growth and positive effects on later development depending on the conditions. It’s a step forward in understanding how chemicals can shape plant genetics and opens doors for potential new breeding strategies, while also reminding us to be mindful of the impact of such compounds.

Source: Springer