Teaming Up Against Superbugs: How Phages Boost Antibiotics for VAP

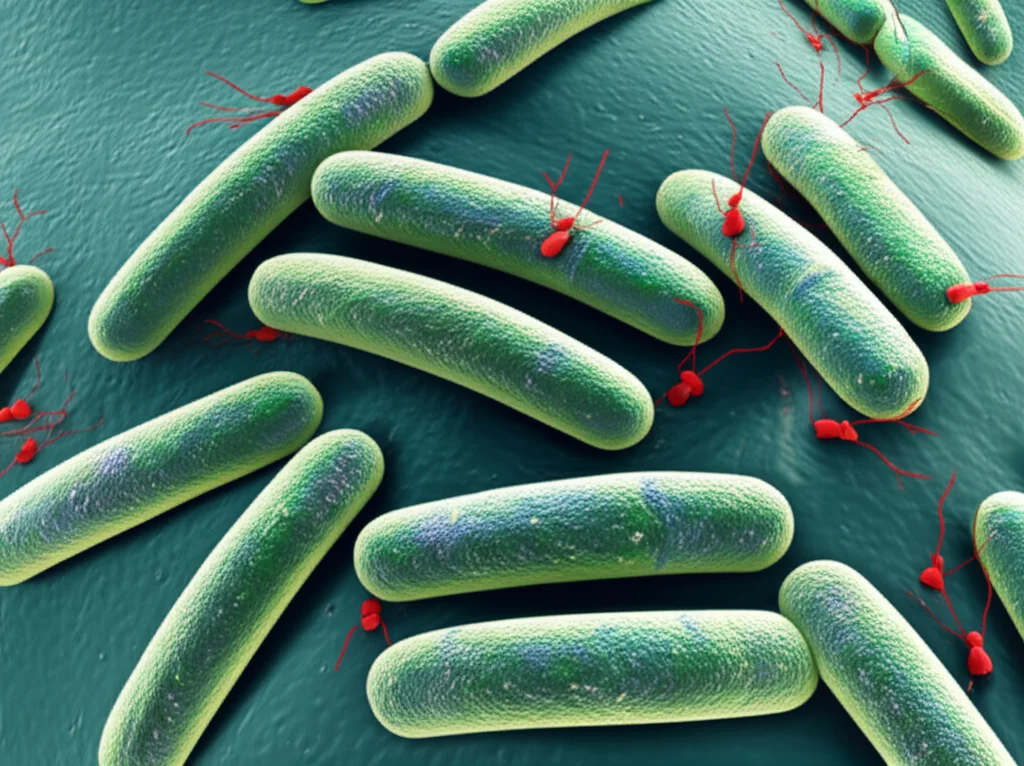

Hey there! Let’s chat about something pretty serious in hospitals, especially in intensive care units: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia, or VAP. You know, when folks are on breathing machines and get a nasty lung infection. It’s a big deal, and unfortunately, it’s often caused by bacteria that are super tough to kill, like *Pseudomonas aeruginosa*, which has become a real multi-drug resistant (MDR) nightmare.

The VAP Problem and the Antibiotic Wall

So, VAP hits the most vulnerable patients, making their hospital stay longer, costing more, and sadly, increasing the risk of not making it. We’ve got antibiotics, sure, and they’re the go-to. Meropenem, for instance, is often recommended, but here’s the rub: using these powerful drugs can actually *select* for even tougher, resistant bugs. It’s like fighting a battle where your main weapon makes the enemy stronger over time. Plus, antibiotics are a bit like a bulldozer – they kill the bad guys, but they also mess up the good bacteria in our bodies and can have some rough side effects. We’re really in need of new ways to fight these infections because the traditional antibiotic pipeline is, well, a bit dry.

Enter the Phages: Nature’s Tiny Assassins

This is where things get interesting. Have you heard of bacteriophages? Think of them as viruses that *only* infect and kill bacteria. Pretty neat, right? They’re super specific, which means they don’t harm our own cells or our friendly gut bacteria. Sounds like a silver bullet! And in lab tests and some individual patient cases, they’ve shown real promise against these stubborn MDR bugs. Even better, they haven’t really shown serious side effects in trials so far.

But, and it’s a big ‘but’, when phages have been tried alone in some clinical trials, they haven’t always hit it out of the park. Maybe the dose wasn’t right, or maybe the bacteria figured out how to resist the phages too. Yep, bacteria are clever; they can develop resistance to phages just like they do to antibiotics.

What If We Teamed Up? The Adjunctive Approach

This got scientists thinking: instead of using phages *instead* of antibiotics, what if we used them *together*? Like a tag team! This idea, called adjunctive phage therapy, is being explored, and that’s exactly what this study dives into. They used a model with mice that developed VAP caused by *Pseudomonas* and also worked with human lung cells in the lab to see if adding phages to standard antibiotic treatment (meropenem) would be better than using either alone.

Testing the Dream Team: The Mouse Model

So, here’s what they did: they gave mice VAP with *Pseudomonas* and then treated them with either meropenem alone, the phage cocktail alone, or a combination of both. They also had a control group that got nothing. They checked how the mice were doing clinically, looked at their lungs and other organs, and measured the amount of bacteria and inflammatory markers.

Turns out, the mice who got the combination therapy looked better, faster. Their clinical scores improved significantly compared to those just getting meropenem or nothing. While all the treatments helped reduce the bacterial load in the lungs and elsewhere compared to no treatment, the combination group really stood out in terms of overall recovery speed.

Beyond Bacteria: Inflammation and Damage

It wasn’t just about killing bacteria, though. VAP causes a lot of inflammation and can damage the delicate lung tissue and other organs. The study checked for inflammatory signals (cytokines) in the lung fluid and markers of organ damage in the blood.

Interestingly, both the phage-only group and the combination group had significantly lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to the untreated group. The meropenem-only group also saw some reduction, but the levels were still higher than with the phage treatments. This suggests phages might help calm down that excessive inflammatory response.

Even more importantly, the combination therapy, like the phage-only therapy, seemed to protect the lung barrier from damage. Meropenem alone, despite killing bacteria, didn’t prevent this damage as effectively. This is a big deal because lung barrier damage is a major problem in severe pneumonia. They also saw less liver injury markers with phage or combination therapy compared to the control.

Diving Deeper: The Lab Work with Human Cells

To understand *how* this combination works so well, they moved to the lab, using human lung epithelial cells and *Pseudomonas*. They mimicked the stress of mechanical ventilation on the cells and then infected them.

What they found was pretty fascinating. The combination therapy killed the bacteria faster than meropenem alone and kept the bacterial levels down longer than phages alone. Remember how phages alone can sometimes lead to resistant bacteria growing back? The combination therapy seemed to prevent that outgrowth.

The real kicker? The combination therapy was effective even at much lower concentrations of both the antibiotic and the phages than when they were used alone. This is huge because lower doses mean fewer potential side effects and less pressure for resistance to develop.

Why the Combo Shines: Beyond Just Killing

They also looked at how the different treatments affected the lung cells directly. When bacteria are killed, they release stuff, including endotoxins, which can be toxic to our cells. Both meropenem and phages caused bacteria to release endotoxins, but surprisingly, the amount wasn’t significantly different between the two after a while.

However, when they exposed lung cells to the liquid from bacterial cultures killed by meropenem, the cells got damaged, and the lung cell layer became leaky. But when they used liquid from bacteria killed by phages, the cells were fine! This suggests meropenem might trigger the release of other harmful bacterial factors, perhaps proteins, that phages don’t. The combination therapy, especially at later time points when phages had done their fast work, resulted in much less cell damage, similar to the phage-only treatment.

This tells us that the benefit of the combination isn’t just about killing bacteria more effectively. It’s also about *how* the bacteria are killed and what gets released. Phages cause bacteria to burst (lyse) in a specific way as part of their life cycle, which seems less damaging to our cells than the way meropenem kills them. By combining the fast, less damaging kill of phages with the sustained effect of meropenem, you get better bacterial control *and* less harm to the patient’s lungs.

Delaying Resistance, Reducing Doses

Another massive advantage is the potential to delay resistance. Using a combination makes it harder for bacteria to become resistant to both agents at once. This study’s in vitro results strongly support this, showing less outgrowth of resistant strains with the combination. Being able to use lower doses of meropenem is also fantastic, as it reduces the selection pressure for antibiotic resistance and minimizes antibiotic side effects.

Looking Ahead: A Promising Future?

So, what’s the takeaway? This study, using mouse and cell models, makes a strong case for adjunctive phage therapy for VAP caused by *Pseudomonas*. It suggests this approach could lead to faster recovery, less inflammation, less lung damage, better bacterial control, and reduced resistance development compared to using antibiotics or phages alone.

Of course, this was done with a specific lab strain of *Pseudomonas* and mostly in female mice (to keep things consistent, you know how biology can vary!). Future studies will need to look at different clinical strains and maybe include male mice too. But the results are really encouraging.

This isn’t just about *Pseudomonas* VAP either. The principles could apply to other nasty MDR bacterial infections. The idea of a therapy that not only kills the bug but also protects the host tissue and helps preserve our existing antibiotics is incredibly exciting. It feels like we’re finally getting some powerful new tools to fight these superbugs, and teaming phages up with antibiotics could be a real game-changer in critical care.

Source: Springer