Peeking Inside PbWO4 Crystals: What Nano-Mechanics Tell Us

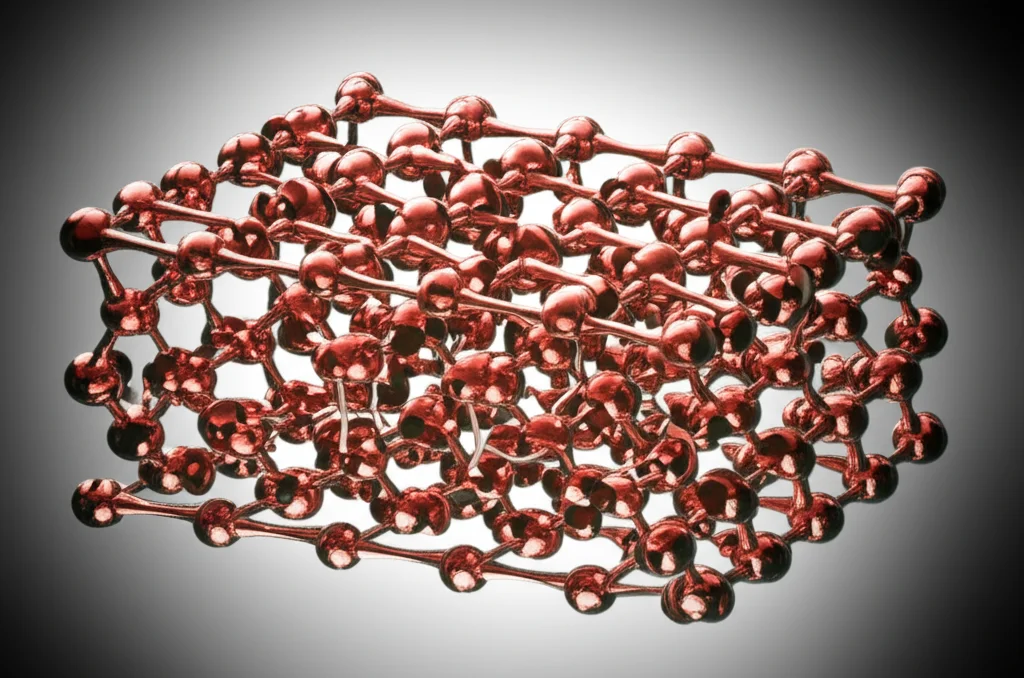

Hey there! So, you know how sometimes you hear about these amazing materials that are doing cool stuff in high-tech gadgets or big science experiments? Well, let me tell you about one of them: Lead Tungstate, or PbWO4 if you want to sound fancy. It’s this neat inorganic crystal that’s already a bit of a star, especially in things like detecting radiation. Think big particle physics experiments or medical imaging – PbWO4 is often in the thick of it, acting as a scintillator or X-ray detector. Its structure is pretty solid, like a well-built LEGO castle, made of Pb²⁺ and WO₄²⁻ bits all locked together in a tetragonal system. This structure gives it some sweet properties, like a high refractive index (great for catching light!) and a wide bandgap (keeps the noise down). Plus, it’s dense, which is exactly what you want when you’re trying to stop energetic particles dead in their tracks.

But here’s the thing: while we know a lot about its optical and structural quirks, understanding how tough it is, especially at a super tiny level, is just as crucial. Why? Because whether it’s being zapped by radiation or integrated into delicate electronic components, its mechanical strength and how it deforms really matter. Is it going to crack under pressure? Can you polish it without it falling apart? These are big questions for engineers and scientists trying to push the boundaries.

Why Mechanical Properties are a Big Deal

Honestly, knowing a material’s mechanical properties is like knowing a person’s resilience. It tells you if it can handle the stress, how long it might last before getting tired (fatigue life), and if it’s going to snap or just bend a little when things get tough. For materials used in cutting-edge tech like microelectronics or high-temperature applications, this isn’t just interesting info; it’s absolutely essential. It dictates where and how you can actually *use* the stuff.

Now, PbWO4 is known to be a bit on the brittle side. Imagine trying to work with a tiny, delicate glass sculpture. Traditional ways of testing strength often involve hitting or pushing on a big piece of material, which can be tricky or even impossible with small, fragile single crystals without just breaking them. That’s where a super cool technique called nanoindentation comes in.

Enter Nanoindentation: Our Tiny Detective

Nanoindentation is like using a microscopic finger to poke a material and see how it responds. It lets us measure things like hardness and stiffness (Young’s modulus) on incredibly small scales, with really high precision. It’s perfect for materials like PbWO4 because we can test tiny spots without wrecking the whole crystal. People have looked at PbWO4’s mechanical side before using other methods, checking out things like internal stress or using microindentation (a slightly bigger poke). But using nanoindentation for the first time to get these specific hardness and Young’s modulus numbers? That was our mission! We wanted to see how these properties behaved when we applied different amounts of force, from a gentle nudge to a slightly firmer press.

We grew our PbWO4 crystals using a standard method called the Czochralski method – basically, pulling a crystal slowly out of a molten bath of the ingredients. Think of it like pulling candy out of syrup, but way more high-tech and precise! We used super pure starting stuff and controlled everything carefully – temperature, pulling speed, rotation speed. Once we had a nice single crystal, we polished it up mirror-smooth and checked its structure with X-ray diffraction (XRD) just to make sure it was the right stuff, which it was! The XRD pattern confirmed our crystal had that desired tetragonal structure.

The Nano-Poke Experiment

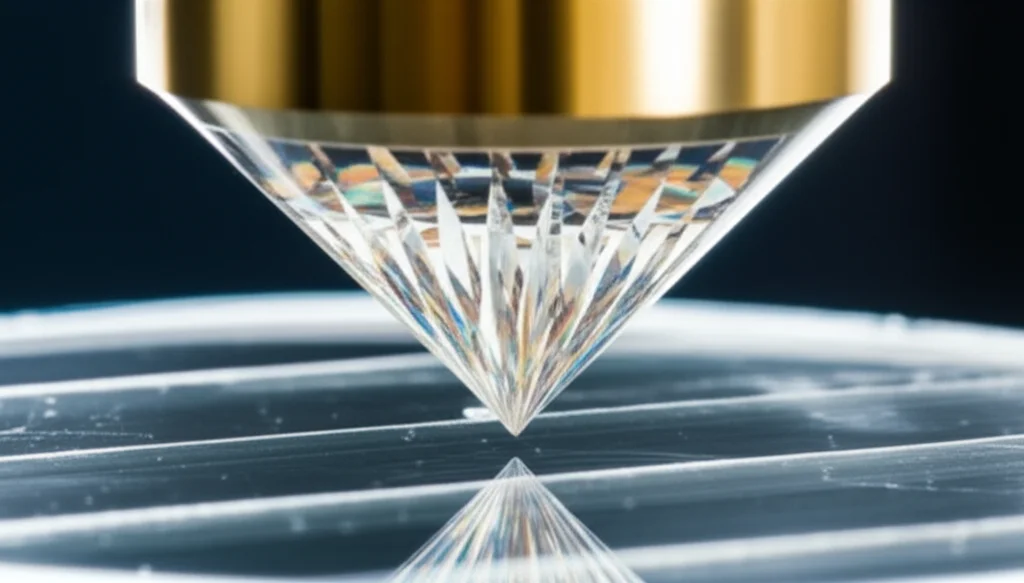

For the nanoindentation, we used a special system with a tiny diamond tip shaped like a three-sided pyramid (a Berkovich tip). We poked the crystal surface multiple times at different spots with forces ranging from 5 to 100 mN (that’s milliNewtons, tiny forces!). The system measures how deep the tip goes for a given force and how it springs back when the force is removed. This load-versus-penetration depth data is the key to unlocking the mechanical secrets. We did multiple tests to make sure our data was reliable and tossed out any weird results.

Interestingly, at higher forces, we sometimes saw sudden little jumps in how deep the tip went. These are called “pop-in” events, and they often signal the start of plastic deformation – where the material permanently changes shape, like bending a paperclip. It’s the crystal rearranging itself under the stress. But don’t worry, the math used to calculate hardness and modulus (the Oliver-Pharr method) is designed to handle this by looking at how the material springs back (the unloading part of the curve).

What the Numbers Told Us: Hardness and the ISE

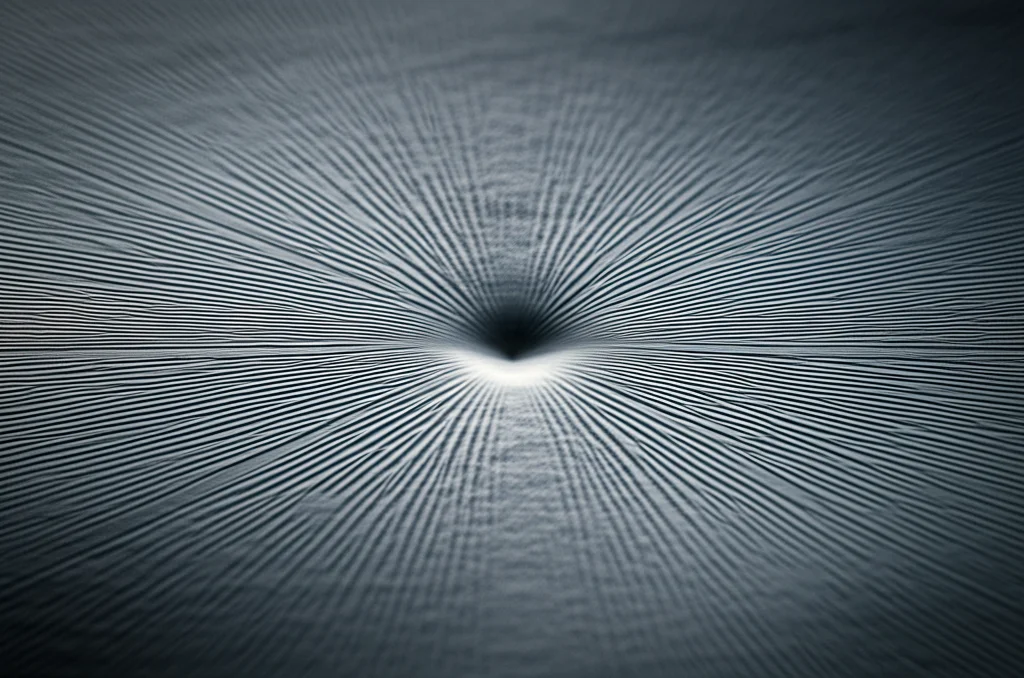

When we crunched the numbers for hardness, we saw something really common at the nanoscale: the Indentation Size Effect (ISE). Basically, the measured hardness wasn’t constant; it decreased as we applied more force (and the tip went deeper). It’s like the material seems harder when you poke it just a tiny bit compared to a slightly bigger poke. This effect happens for various reasons at the micro and nano levels, involving things like how dislocations (defects in the crystal structure) move around or surface effects.

To figure out the material’s “true” hardness, independent of this size effect, we used a model called the Proportional Specimen Resistance (PSR) model. By analyzing how the force-to-depth ratio changed, this model helped us separate the intrinsic material toughness from the size-dependent effects. And the result? The true hardness value for our PbWO4 crystal came out to be around 2.87 GPa. We also looked at the data using something called Meyer’s law, which gives us a Meyer’s index. Ours was 1.77, and since that’s less than 2, it further confirmed that yep, the ISE is definitely happening here.

Young’s Modulus: Stiffness and Cracks

Next up was Young’s modulus, which tells us how stiff the material is – how much it resists elastic deformation (springing back to its original shape). We saw a similar trend here as with hardness: the Young’s modulus also decreased as we increased the load. It dropped from 82.0 GPa at the lowest force (5 mN) down to 71.1 GPa at the highest (100 mN).

Why the drop in stiffness? The study suggests this is likely due to the formation of tiny cracks within the material under the indenter. Imagine the crystal lattice as a network of springs (atomic bonds). When cracks form, some of these springs are broken, making the overall network less stiff. It’s like having a few broken springs in a mattress – it just doesn’t feel as firm. Researchers have modeled this using concepts like the Lennard-Jones potential, which describes how atoms interact. Essentially, microcracks disrupt the atomic bonding energy, leading to a lower effective stiffness, or Young’s modulus. This highlights that even at these small scales, how the material fractures or cracks plays a big role in its elastic response. The data also allowed us to extrapolate back to zero load to get an “intrinsic” Young’s modulus value, which was around 82.1 GPa, matching the value seen at the lowest loads before cracking effects become more prominent.

Elastic vs. Plastic: Who’s Dominant?

Another cool thing nanoindentation lets us do is figure out how much of the deformation is elastic (temporary, springs back) versus plastic (permanent, stays deformed). Using a model called the Sakai model, we separated these two components.

And the results were pretty clear: plastic deformation was the boss here. As we increased the load, the percentage of plastic deformation actually went up slightly, from 84.0% to 85.6%. Elastic deformation accounted for the remaining 16.0% down to 14.4%. This is a significant finding! Even though PbWO4 is considered brittle, the fact that plastic deformation is the dominant mechanism under indentation suggests it has a decent capacity to deform permanently rather than just shattering immediately. This relates to its resistance to fracture. We also looked at a parameter called KT, which represents resistance to plasticity, and it decreased with load, again pointing towards a dominant plastic behavior in this load range.

Wrapping It Up: Why This Matters

So, what have we learned from our nano-poking adventure with PbWO4?

- We confirmed the presence of the Indentation Size Effect (ISE) for both hardness and Young’s modulus.

- We determined the true hardness to be about 2.87 GPa using the PSR model.

- We saw that the Young’s modulus decreases with increasing load, likely due to microcracking affecting the material’s stiffness.

- Crucially, we found that plastic deformation is the dominant mechanism under these indentation loads.

These findings are more than just interesting academic points. Knowing these nanomechanical properties is vital for optimizing PbWO4 for its current gigs in radiation detection (where durability under bombardment is key) and for exploring new possibilities. Its combination of useful optical/structural properties and this revealed elastic-plastic behavior (meaning it’s not *purely* brittle and can handle some deformation) makes it a promising candidate for future applications in delicate optoelectronic and photonic devices, where materials need to be stable and resistant to stress at tiny scales. It seems our little PbWO4 crystal is tougher and more versatile than a simple “brittle” label might suggest!

Source: Springer