Unlocking NV Center Power: Full Qubit Control for Better Sensing

Hey there! So, you know those cool quantum sensors made from defects in diamond? We’re talking about negatively charged nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers. These little guys are pretty amazing for sensing stuff like magnetic fields, temperature, and electric fields. Their ground state is a spin-1 triplet, which basically means it has three energy levels, and it can stay coherent for a good long while, even at room temperature. This makes them super useful, especially for things like nanoscale nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), which could help us figure out the structure of tiny molecules.

The Usual Way vs. The Problem

Now, typically, when folks work with these NV centers, they kind of ignore one of the three levels. They focus on the transitions between the |0> state and either the |-1> or |+1> state. This works fine *if* the energy difference between the levels you’re using and the third one is way bigger than the strength of the pulses you’re hitting them with. But what happens when that’s not the case? Well, you get “leakage” – population spills into that third level you were trying to ignore. This is a real bummer because it messes up your operation.

This leakage problem creates two big headaches for sensing:

- You can’t easily sense high-frequency signals with standard techniques.

- You can’t operate effectively in low magnetic fields.

And operating in low fields is actually super important for a bunch of cool applications, like making carbon-13 spins polarized (which helps NMR!), sensing molecular structures via J-coupling, and imaging magnetic textures in fancy materials like superconductors or skyrmions. High fields can actually hide the signals you’re looking for or introduce other annoying effects. Being able to work in low fields also helps us understand the fuzzy line between quantum and classical noise and improves experiments with lots of NV centers at once.

Enter NV-ERC: A Smarter Pulse Strategy

Luckily, there’s a technique called NV effective Raman coupling (NV-ERC). This method is pretty clever because it designs pulses that *do* take the third level into account. By zapping the NV center with a microwave frequency that matches its zero-field splitting (that’s the energy difference between |0> and the average of |+1> and |-1> when there’s no magnetic field), you can actually prepare the NV center into a state on the “equator” of the double quantum transition (that’s the space defined by the |+1> and |-1> states) *without* losing population to the |0> state. Pretty neat, right?

This NV-ERC approach has been shown to work experimentally for initializing and reading out the double quantum transition. People have even tried to use the phase of the pulses to do effective rotations within this double quantum space, which is key for building complex sensing sequences. However, the big missing piece was a *complete theoretical understanding* of exactly what was happening during these NV-ERC pulses. Without that full picture, it was tough to design *any* arbitrary control sequence, not just simple rotations.

Our Contribution: The Full Theoretical Picture

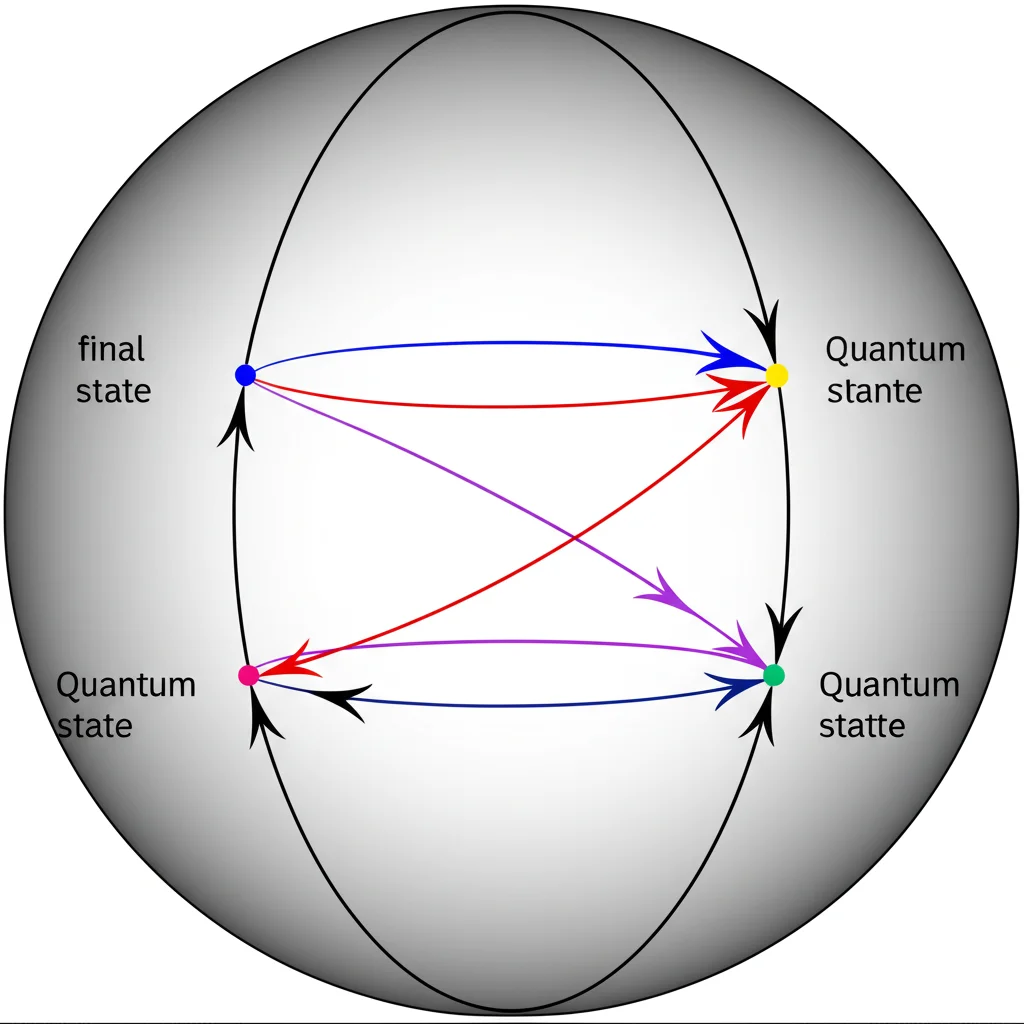

That’s where our work comes in! We dove deep to figure out the *full* theoretical framework for the NV-ERC scheme. We analytically derived the complete unitary transformation associated with the NV-ERC pulse. Think of the unitary transformation as the mathematical description of exactly how the quantum state changes over time when you apply the pulse.

We specifically looked at two characteristic pulse durations, which we call (bar{T}’) and (bar{T}”). Previous work had shown that a pulse of duration (bar{T}’) could map the |0> state to a state on the double quantum Bloch sphere equator, but they didn’t fully analyze the phase acquired or what happened to the other states. We figured out the *entire basis transformation* for both (bar{T}’) and (bar{T}”) pulses, including all the phases involved. This gives us a much deeper understanding of how the three-level system behaves.

For a pulse of duration (bar{T}’), we found that:

- The |0> state maps to a specific state on the double quantum equator, acquiring a phase related to the pulse phase.

- Another state, orthogonal to the target state, maps from a different state on the double quantum sphere, acquiring a phase of (pi).

- The third state, orthogonal to the second one, maps back to the |0> state, acquiring a phase related to the pulse phase.

We did a similar analysis for the (bar{T}”) pulse, which basically performs the opposite transformation. Having this complete picture – knowing exactly how *all* three states transform and what phases they pick up – is the key to unlocking full control.

Building Any Gate You Want

With this newfound understanding of the unitary transformations for (bar{T}’) and (bar{T}”), we can now design sequences of pulses to perform arbitrary operations on the double quantum transition qubit (the |+1> and |-1> subspace). It turns out you can do any single-qubit gate by combining rotations around just two non-parallel axes on the Bloch sphere.

We showed that by concatenating a (bar{T}’) pulse with phase (alpha) and a (bar{T}”) pulse with phase (alpha + theta), you get a rotation of angle (theta) around a specific axis. The axis depends on the ratio of the Rabi frequency ((Omega), related to pulse strength) and the magnetic field ((mu B)). This is pretty cool because it means you can control the rotation angle by changing the phase difference (theta).

Even better, we found a second way to get rotations around a *different* axis: just reverse the order of the pulses! Concatenating (bar{T}”) then (bar{T}’) gives you a rotation around the opposite axis. As long as your pulse strength is above a certain threshold relative to the magnetic field, these two axes will be different. Voilà! We have rotations around two non-parallel axes, which means we can combine them to perform *any* arbitrary single-qubit gate on the double quantum transition. And the best part? You can achieve this with pulses of constant frequency and amplitude, simply by carefully timing the phase changes.

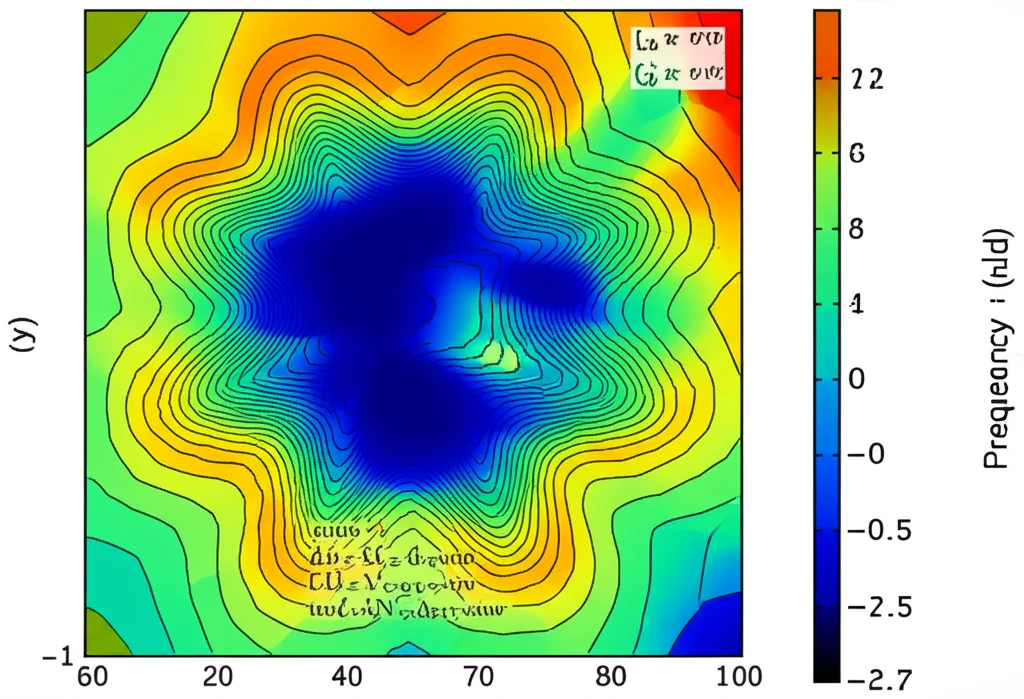

Handling the Real World: Errors and Fields

Of course, real experiments aren’t perfect. We also looked at how robust our scheme is against common errors. We considered errors in identifying experimental parameters (like pulse strength or magnetic field), errors due to phase changes not happening instantaneously (sluggishness), and simple timing errors in the pulses. We found that parameter and phase errors can often be thought of as types of timing errors, simplifying the analysis.

Our study showed that the scheme has good robustness, although the specific timing combination that is most robust depends on the ratio of pulse strength to magnetic field. For example, in the low-field/high-power regime, the scheme is less sensitive to errors in how the total pulse time is split between (bar{T}’) and (bar{T}”), as long as the total time is correct. In the high-field/low-power regime, it’s the opposite – the difference between (bar{T}’) and (bar{T}”) is more critical than the total time. This insight helps experimentalists know what to focus on for calibration depending on their operating regime.

What about pesky static electric fields or strain in the diamond? These can definitely affect the NV center’s energy levels. We showed that our scheme can adapt to these too. The standard experimental steps used to characterize the NV center – measuring its energy levels with ODMR and finding the characteristic pulse times ((bar{T}) and (bar{T}’)) with a Rabi experiment – automatically account for most of these static perturbations. For example, an electric field component along the NV axis just shifts the zero-field splitting, which is picked up by ODMR. Other components might effectively change the magnetic field strength or rotate the double quantum space, but these effects are captured when you measure (bar{T}) and (bar{T}’) experimentally. Even a trickier field component can be compensated for by adding a second microwave pulse in a different direction, and the correct ratio of pulse strengths can be found experimentally by seeing what best depletes the |0> state. So, the scheme is surprisingly resilient to these common imperfections in the diamond environment.

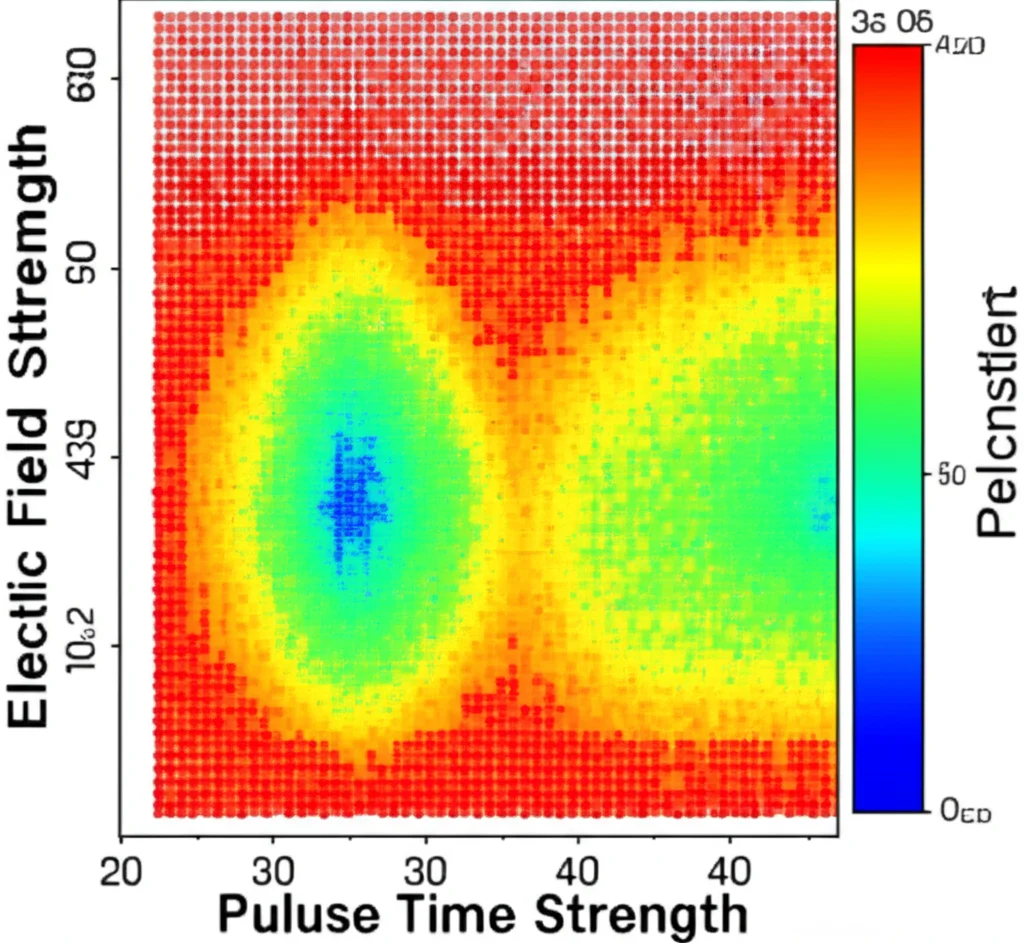

Testing it Out: Hahn Echo for Sensing

Finally, we put our scheme to the test numerically by simulating a classic sensing sequence: the Hahn echo. The Hahn echo is used to detect oscillating magnetic fields. In conventional NV sensing using the single quantum transition, the finite duration of the pulses limits the maximum frequency you can reliably sense. If the signal frequency is too high, the pulse duration becomes a significant fraction of the waiting time, messing up the sequence. Increasing the pulse strength to make them shorter often leads to that unwanted leakage we talked about, killing sensitivity.

Our NV-ERC approach solves this! We showed numerically that a Hahn echo sequence built using our (bar{T}’) and (bar{T}”) pulses on the *double quantum transition* is effective for sensing signals with frequencies comparable to the Zeeman splitting ((sim mu B)), which is exactly the low-field/high-frequency regime where conventional methods struggle. Because the NV-ERC pulses are designed to avoid leakage even at high power, you *can* increase the pulse strength ((Omega)) to make the pulses shorter. This pushes the maximum detectable frequency higher *without* the detrimental effects seen in conventional sensing. Plus, sensing on the double quantum transition inherently gives you a twofold sensitivity boost compared to the single quantum transition.

Wrapping It Up

So, to sum it all up, we’ve provided the missing theoretical piece for the NV-ERC technique, giving us a full understanding of how the quantum states evolve during these special pulses. This allowed us to propose a scheme for performing *any* single-qubit gate on the double quantum transition of the NV center, simply by controlling the phase and timing of pulses tuned to the zero-field transition. We showed that this approach is robust against common experimental errors and can seamlessly adapt to the presence of unknown static electric or strain fields. Finally, our numerical tests demonstrated that this full control enables effective quantum sensing in regimes (low magnetic fields, high signal frequencies) where conventional methods fall short, particularly highlighted by its performance in a Hahn echo sequence. This work opens up exciting possibilities for using NV centers in diamond for advanced quantum sensing applications.

Source: Springer