Cracking the Code: A Nifty New Tool for Designing Next-Gen Superconductors!

Hey there, science enthusiasts! Ever heard of topological superconductors? If not, buckle up, because these materials are seriously cool and could be the key to unlocking the power of topological quantum computation. The catch? Finding them and designing them has been a bit of a head-scratcher. But guess what? We’ve been cooking up something special – a numerical method that’s about to make this quest a whole lot easier. Let’s dive in!

So, What’s the Big Deal with Topological Superconductors?

Alright, let’s get a bit nerdy, but I promise to keep it fun. The whole idea of topological superconductors popped up back in 2000. Think of them as special states of matter that can host these super exotic particles called Majorana zero modes. Now, why should you care about Majorana zero modes? Well, these little guys are their own antiparticles (mind-bending, right?) and are incredibly promising for building super-stable qubits – the building blocks of quantum computers. Imagine quantum computers that are much less prone to errors! That’s the dream, and topological superconductors (TSCs) are a big part of it.

Traditionally, everyone thought p-wave superconductors were the go-to for finding these Majorana modes. But here’s the rub: intrinsic p-wave superconductivity is as rare as a unicorn, and actually spotting Majorana states in these systems? Even tougher. So, for the last decade, clever folks have been figuring out ways to induce topological superconductivity. How? By cleverly layering materials, like putting an s-wave superconductor (the more common kind) next to a topological insulator or a semiconductor with something called Rashba spin-orbit coupling. It’s all about that proximity effect – getting materials to “talk” to each other and share their cool properties.

The Challenge: From Theory to Reality

Now, despite all this awesome theoretical progress, actually finding and confirming TSCs in the lab has been slow going. A big reason is that our theoretical models are often a bit too simple. They’re like a sketch of a complex machine – they give you the basic idea but miss a lot of the nitty-gritty details of real materials, like their intricate electronic structures.

This is where our new tool comes into play! We’ve developed a numerical method that takes a much more realistic approach. It uses first-principles band structure calculations (that’s a fancy way of saying we’re starting from the fundamental quantum mechanics of the material) and a phenomenological theory for how that superconducting proximity effect actually works, especially how the superconducting pairing might decay as you move away from the superconductor interface. And the best part? We’ve implemented it in the open-source software WannierTools. This means we can get a much more accurate picture of what’s happening with the electrons in these materials.

The whole process, which we’ve mapped out (kinda like a treasure map for physicists!), starts with building these things called Wannier functions from those first-principles calculations. These functions give us a super precise description of the material’s electronic structure. Then, we simulate the s-wave superconducting pairing and any spin splitting (if we’re using magnetic materials) at the interface of a 2D slab of the material. This lets us build what’s called a Bogoliubov-de Gennes (BdG) Hamiltonian – a mathematical framework that describes the superconducting state. From there, we can investigate all sorts of superconducting properties and, crucially, calculate the topological invariants that tell us if we’ve hit the topological jackpot.

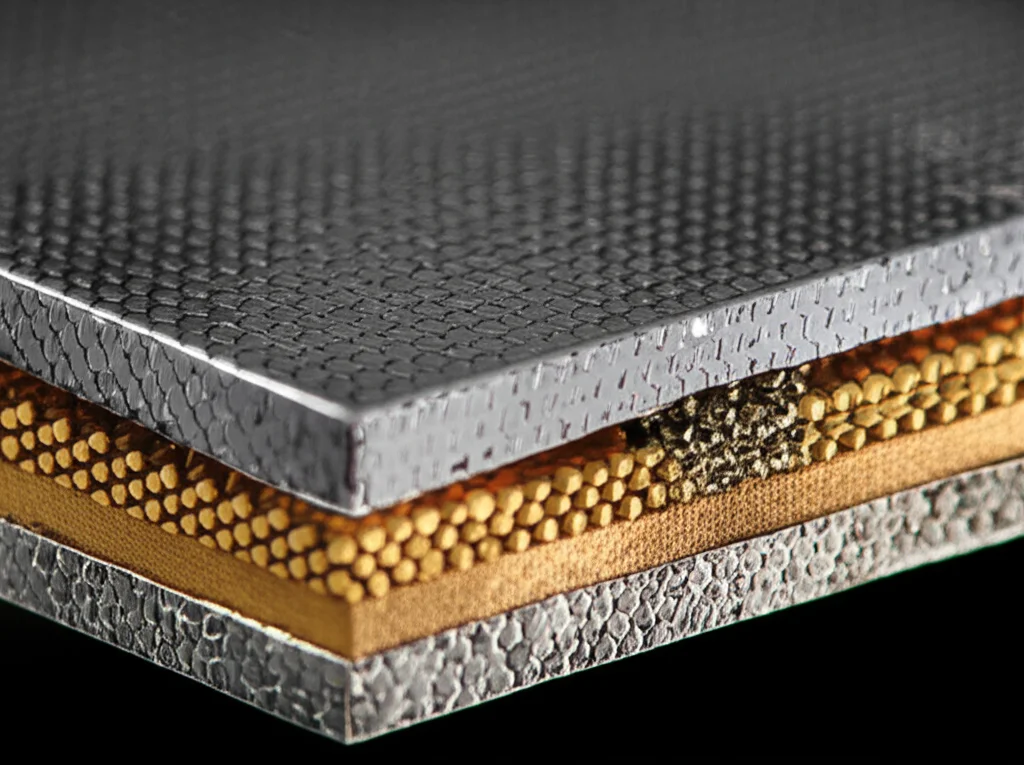

We’re particularly excited about using this for heterostructures – those layered cake-like systems. Think a superconductor, our candidate material, and maybe a ferromagnetic insulator all sandwiched together. Our method is robust enough to predict and characterize TSCs in these kinds of setups, which are much more like what experimentalists can actually build and test.

Getting Down to the Nitty-Gritty: How It Works

One of the most efficient ways to build a model (a tight-binding Hamiltonian, for the purists) for a real material is using something called maximally localized Wannier functions (MLWFs). The Wannier90 software package is a champ at this, and it can talk to all sorts of first-principles calculation codes like VASP, Wien2k, and Quantum ESPRESSO. So, we can automatically generate these Hamiltonians, which basically tell us how electrons hop around in the material.

To really study these proximity effects in heterojunctions, we need to simulate a surface or interface. We do this by using “open boundary conditions.” Imagine you have a 3D crystal; we essentially slice it to create a 2D slab, keeping the periodic nature in the plane of the slab but opening it up in the direction perpendicular to the surface. Sometimes, the way we need to “slice” the material for an experiment doesn’t line up perfectly with how the crystal is naturally defined. No worries! Our method can handle that too, by redefining the basis vectors. This lets us look at any dissociation surface we want.

Once we have our 2D slab Hamiltonian, we can introduce the fun stuff. If there’s a magnetic material nearby (like in our superconductor/candidate/ferromagnetic insulator sandwich), we add an exchange effect, which is basically a spin splitting, to the surface layer. Then, to get the full BdG Hamiltonian for our heterojunction, we induce superconducting pairing across the whole system. Since most superconductors used for this are s-wave, we stick with intra-orbital s-wave pairing.

The Fading Superconductivity: A Realistic Touch

Here’s a crucial bit: that superconducting magic doesn’t just instantly appear everywhere in the candidate material when it’s next to a superconductor. The superconducting gap induced by the proximity effect actually decays the further you get from the superconductor interface. It’s like a whisper that gets fainter with distance. We’ve incorporated a model for this decay that depends on things like temperature, the superconducting correlation length, and the mean free path of electrons in the candidate material.

We even checked this decay model against real experimental data for an NbSe2/Bi2Se3 heterostructure, and guess what? It fits pretty darn well! So, when we’re modeling these heterostructures, we use this more realistic, layer-dependent superconducting gap. This is super important because, as we’ll see, it can really change whether a material becomes a topological superconductor or not.

Spotting the Topology: Chern Numbers and Z2 Invariants

Okay, so we have our BdG Hamiltonian. How do we know if it’s describing a topological superconductor? We need to calculate its topological invariants. These are numbers that characterize the “shape” or topology of the electronic bands. For 2D systems, if time-reversal symmetry (a fundamental symmetry in physics) is broken, the system is classified by an integer called the Chern number. If time-reversal symmetry is preserved, it’s classified by a Z2 topological number. Fun fact: if you have a system with both time-reversal and inversion symmetry, s-wave pairing usually just gives you a topologically boring (trivial) phase.

There are many ways to calculate these invariants, but we use the Wannier charge centers (or Wilson loop) method. It’s versatile and can give us both the Z2 number and the Chern number. In WannierTools, we’ve implemented an algorithm that looks at how these Wannier charge centers evolve. It’s a well-established method, and it tells us the topological properties of our 2D system. One little detail: in the BdG spectrum, the number of occupied states is always half the total, so we compute the Wilson loop for half of the spectrum.

From Simple Models to Real Materials: Putting It to the Test

Let’s talk about how we can get topological superconductivity. If you take a 3D strong topological insulator (TI) and slap an s-wave superconductor on it, you can, under the right conditions, get an effective p+ip-wave pairing. But, this system still has time-reversal symmetry, so no chiral boundary states (a hallmark of some TSCs). To get those, you need to break time-reversal symmetry, for example, by introducing a magnetic exchange effect. If this exchange effect (let’s call it Mz) is strong enough – specifically, if |Mz| > √(μ2+Δ2), where μ is the chemical potential and Δ is the superconducting pairing strength – then boom! You can get a topological phase characterized by a Chern number.

This idea also works for 2D systems with Rashba spin-orbit coupling. Break time-reversal symmetry, and you can achieve topological superconductivity. So, our general setup is this superconductor-candidate material-ferromagnet heterostructure. The top surface of our candidate material gets its superconductivity from the superconductor, and the bottom surface feels the magnetic field from the ferromagnet. This can create two Dirac cones (special features in the electronic structure) with different “mass” terms, which is a recipe for a chiral topological superconducting state!

Example 1: A Toy Model Topological Insulator

Before jumping into real materials, we always like to test things on a simpler model. We cooked up a tight-binding model for a topological insulator on a simple cubic lattice. We set the parameters so it’s in a “strong TI” phase. Then, we made a 20-layer slab and looked at its surface states – yep, Dirac cone, just as expected!

Next, we introduced uniform superconducting pairing (Δ=0.1) and set the chemical potential to zero. Without any magnetic spin splitting (Mz=0), the system is gapped but topologically trivial (Chern number = 0). But then, we started cranking up Mz. We found a critical point where the BdG spectrum closes and reopens. For Mz beyond this point (0.132 in our model), the system flips into a topological superconducting state with a Chern number of 1! This shows the basic principle: the spin splitting Mz needs to be strong enough to induce this closing and reopening of the gap.

Example 2: The Real Deal – Bi2Se3

Time for a real material! We picked Bi2Se3, a well-known topological insulator. We used first-principles calculations to get a tight-binding model for it. Then, we simulated a 10-layer slab, considering both the superconducting proximity effect (with decay!) and the magnetic proximity effect from an imagined ferromagnetic layer.

Here’s where that decay of superconductivity becomes really important. We plotted a phase diagram showing where the system becomes topological as a function of Mz. We did it with and without considering the decay of the superconducting pairing. The result? When you include the decay, you need less spin splitting to push the system into the topological phase! This makes sense because the topological properties are mainly determined by what’s happening at the interface with the ferromagnet. If the superconductivity (Δ) is weaker there due to decay, then a smaller Mz is needed to satisfy that |Mz| > √(μ2+Δ2) condition. For a fixed Mz = 0.3 eV, without decay, Bi2Se3 was trivial. With decay, it became a topological superconductor with Chern number = -1. This is much closer to what we’d expect in a real experiment.

Example 3: High Chern Numbers with SnTe

Can we get even more exotic? What about topological superconductors with high Chern numbers? For this, we turned to SnTe. It’s a topological crystalline insulator, and its (001) surface has not one, but four Dirac cone surface states! We built a model for a 40-layer slab of SnTe, again including the decaying superconducting pairing and a surface spin splitting.

And the result was pretty spectacular! We found a topological superconducting state with a Chern number of -4! This is exactly what you’d expect. Since time-reversal symmetry is broken, and the four Dirac cones are related by the crystal’s fourfold rotational symmetry, they should each contribute equally to the Chern number. So, a multiple of four it is! This shows our tool can handle these more complex, multi-Dirac-cone systems.

Example 4: Rashba Materials – NbSe2 (Model)

Our method isn’t just for topological insulators. It also works for materials with strong Rashba spin-orbit coupling. We first tested it on a model for monolayer NbSe2, a material whose low-energy physics can be captured by effective d-orbitals on a triangular lattice. We used parameters from a previous study and added a small superconducting pairing (Δ=0.001 eV) and an out-of-plane magnetic field (Bz).

We were able to reproduce their phase diagram perfectly! By tuning the chemical potential and Bz, we found regions with different Chern numbers: C=1, C=2, and even C=-3. The different Chern numbers arise because the chemical potential can intersect band degeneracies at different high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone (the map of electron momenta in the crystal).

Example 5: Rashba Materials – InSb (Real Material)

Finally, we looked at Indium Antimonide (InSb), a semiconductor famous for its use in making Majorana nanowires. We used first-principles calculations (with fancy HSE06 hybrid functionals, for those in the know) to build a tight-binding model. We then looked at a 10-layer slab, carefully treating the “dangling bonds” at the surfaces to get a realistic electronic structure.

Again, by applying a superconducting pairing (with decay) and a magnetic spin splitting, we found topological superconducting states. We focused on states derived from the lowest conduction bands at different points in the Brillouin zone (Γ, X, and Y points). For each of these, we found a topological superconducting state with a Chern number whose absolute value is 1. This makes sense because there’s only one of each of these points in the first Brillouin zone.

Wrapping It Up: A Powerful New Ally

So, there you have it! We’ve developed a pretty neat program, integrated right into WannierTools, that can calculate the superconducting BdG spectrum and topological invariants for 2D systems. We’ve shown it can analyze these complex superconductor/candidate material/ferromagnetic insulator heterostructures and predict whether they’ll be topological superconductors. From model systems to real materials like Bi2Se3, SnTe, and InSb, our tool is up to the task. We even showed SnTe could be a candidate for chiral topological superconductors with high Chern numbers!

We believe this tool will be a massive help in the ongoing hunt for new topological superconductor candidates. It provides strong theoretical backing for experimental exploration and could even be extended to other cool systems, like magnetic topological insulator/superconductor heterostructures. The quest for fault-tolerant quantum computing just got a little bit easier, and I, for one, am super excited to see what new materials and discoveries this will lead to!

The first-principle calculations mentioned were based on density functional theory (DFT) using VASP, with the PBE functional for exchange-correlation (except for InSb), and the PAW method. The TB Hamiltonians were built using Wannier90.

Source: Springer