NRAS Mutation in CMML: Unpacking Insights from Two Major Studies

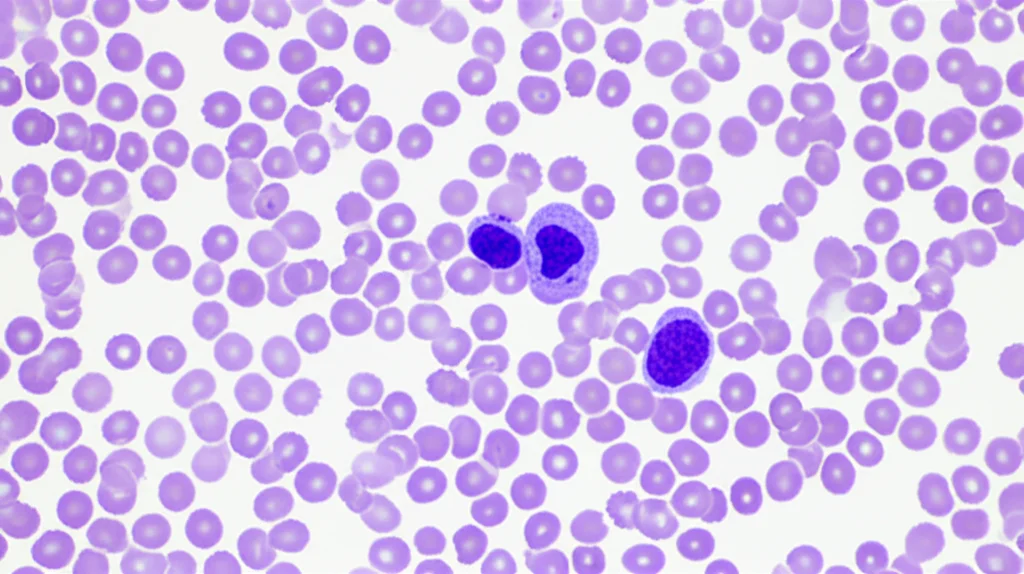

Hey there! Let’s chat about something pretty specific but super important in the world of blood disorders: Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia, or CMML for short. Now, CMML is a bit of a tricky one. Think of it as a hybrid – it’s got features of both myelodysplastic syndromes (where your bone marrow doesn’t make enough healthy blood cells) and myeloproliferative neoplasms (where it makes too many of certain cells, especially monocytes). It’s a rare gig, mostly affecting older folks, and it can be quite unpredictable, sometimes even morphing into acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

For ages, we’ve been trying to figure out what makes one person’s CMML different from another’s. It’s not a one-size-fits-all kind of deal. Outcomes can vary wildly, and we know that lurking beneath the surface are genetic changes, or mutations, that play a big role. Understanding these mutations is key to giving patients the best possible care tailored just for them.

The Gene in Question: NRAS

One particular gene that pops up in CMML is called NRAS. Genes in the RAS pathway are known troublemakers in various cancers, often linked to cells growing and dividing too much. So, it makes sense that a mutation in NRAS might influence how CMML behaves. But here’s the thing: studies looking at the impact of NRAS mutations in CMML have sometimes shown different results. Some found it affected survival, others didn’t. This inconsistency makes it hard to confidently say, “Okay, if you have an NRAS mutation, this is exactly what it means for you.”

Why We Need Big Data and Validation

This is where the concept of “validation” comes in. In science, especially when we find something that might predict how a disease will progress (a prognostic parameter), we need to test that finding in a completely separate group of patients. If the finding holds up in the new group, we can be much more confident it’s real and not just a fluke of the first study group. This is where “big data” is a game-changer. Platforms like cBioPortal collect vast amounts of data from many different studies and patients worldwide. It’s like having a giant library of patient information, perfect for checking if something we saw in a smaller, local group is true on a larger, international scale.

So, picture this: we have a fantastic national database in Austria called ABCMML, which has been diligently collecting detailed information on CMML patients for 40 years. It’s a real-life snapshot of CMML in Austria. We also have the cBioPortal, a huge international resource with data from hundreds of CMML patients. What happens if we use the cBioPortal data to check the characteristics we observed for NRAS-mutated patients in the ABCMML cohort?

Comparing the Cohorts

In this study, we dove into both the ABCMML database (with 327 patients where mutation data was available) and the cBioPortal dataset (with 399 CMML cases). First off, we looked at the basic stuff. Like many CMML studies, both cohorts had more men than women, and over half the patients were aged 70 or older. Pretty typical.

However, there was one notable difference: the ABCMML cohort had a significantly higher proportion of patients with a high white blood cell (WBC) count (over 13 x 10^9/L) compared to the cBioPortal cohort (57% vs. 32%). The median WBC count was also higher in ABCMML (14.1 vs. 9.2 G/L). The folks behind the study suggest this might be because the ABCMML includes older data, and perhaps in recent years, we’re catching CMML earlier due to increased screening, meaning newer cohorts like parts of cBioPortal might have more patients diagnosed before their WBC count gets really high.

Despite this difference in WBC distribution, the overall survival times were quite similar between the two cohorts – a median of 29.0 months in ABCMML and 31.6 months in cBioPortal. This suggests both cohorts, despite the WBC difference, represent a similar overall picture of CMML progression.

NRAS Mutation: Prevalence and Impact on Survival

Now, let’s talk about the star of the show, the NRAS mutation. We found that NRAS mutations were present in a similar proportion of patients in both groups: about 14.6% in ABCMML and 15.7% in cBioPortal. This consistency is good – it means the mutation isn’t just common in one specific population.

Here’s the big finding: In both cohorts, patients with an NRAS mutation had significantly worse survival compared to those without it. Look at the numbers:

- In ABCMML, median survival was 15.0 months for NRAS-mutated vs. 30.0 months for non-mutated patients (a clear difference!).

- In cBioPortal, median survival was 18.5 months for NRAS-mutated vs. 36.3 months for non-mutated patients (again, a significant difference!).

This is a powerful validation. Seeing the same adverse impact in two independent, large cohorts strengthens the case that NRAS mutation is indeed a negative prognostic factor for overall survival in CMML.

It wasn’t just overall survival either. We also looked at AML-free survival – how long patients lived without their CMML transforming into the more aggressive AML. Again, in both cohorts, NRAS-mutated patients had significantly shorter AML-free survival:

- ABCMML: 52.0 months (mutated) vs. 134.0 months (non-mutated).

- cBioPortal: 16.6 months (mutated) vs. 29.7 months (non-mutated).

So, the NRAS mutation seems to be linked to both shorter overall lifespan and a higher risk of transforming to AML.

What About Blood Counts and Other Features?

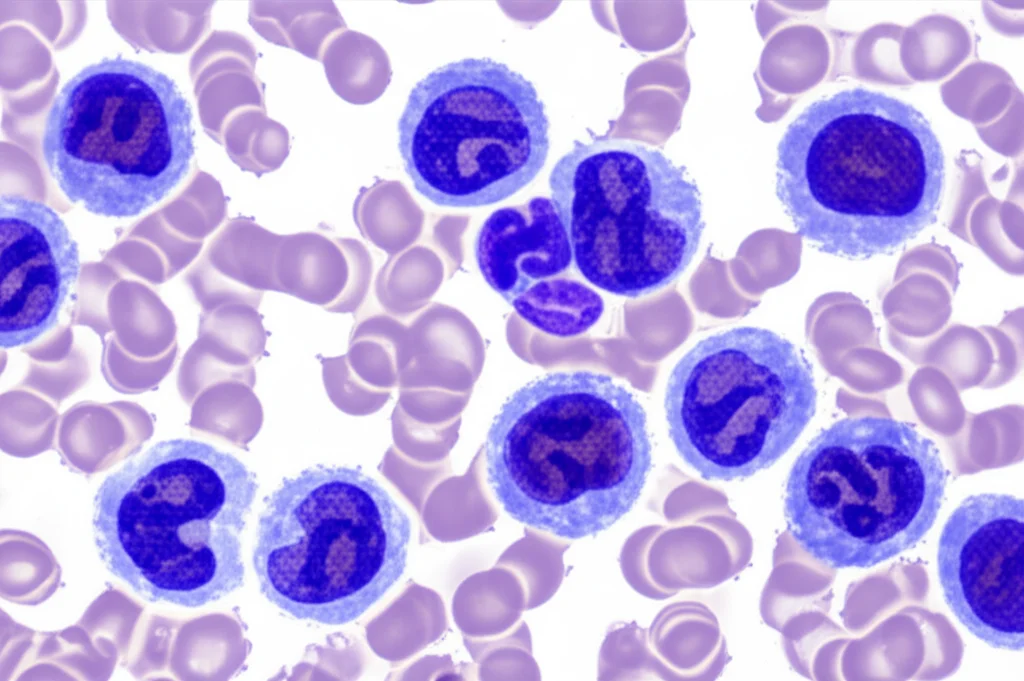

Beyond survival, we checked if NRAS mutation was associated with specific characteristics of the disease, like blood cell counts. And guess what? In both the ABCMML and cBioPortal cohorts, NRAS-mutated patients consistently showed:

- A significantly higher proportion of patients with leukocytosis (high WBC count).

- A significantly higher proportion of patients with circulating blasts (immature white blood cells in the blood, which is a sign of more aggressive disease).

- A significantly higher proportion of patients with thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).

Interestingly, the proportion of patients with anemia (low hemoglobin) didn’t seem to differ much based on NRAS status in either cohort. The median values painted a similar picture: NRAS-mutated patients had higher median WBC counts (around 23 G/L in ABCMML, 20.3 G/L in cBioPortal) compared to non-mutated patients (around 11.4 G/L in ABCMML, 8.8 G/L in cBioPortal). They also had lower median platelet counts (around 88 G/L in ABCMML, 94 G/L in cBioPortal) compared to non-mutated patients (around 126 G/L in ABCMML, 125 G/L in cBioPortal). Hemoglobin levels were quite similar between the groups.

These findings validate previous reports linking RAS pathway mutations to myeloproliferation (high WBC) and increased blasts. The association with lower platelets is a newer observation that was consistent across both cohorts, which is pretty neat.

Putting It All Together: The Importance of Cohort Size

So, why did some earlier, smaller studies miss the significant impact of NRAS on survival? Looking at the data, it seems the size of the patient group really matters. In studies with fewer than 200 patients, the link between NRAS mutation and worse survival wasn’t always clear or statistically significant. But in larger cohorts, like our ABCMML and cBioPortal groups (both over 300 patients), and a couple of other large studies mentioned in the text, the adverse impact of NRAS on overall survival was consistently found to be significant or borderline significant. It’s a bit like trying to spot a subtle trend in a small crowd versus a large one – the larger the group, the clearer the pattern becomes.

Of course, no study is perfect. We already mentioned the difference in WBC distribution between the cohorts, which might reflect changes in how and when CMML is diagnosed over time. Also, the diagnostic criteria for CMML have evolved since the ABCMML database started 40 years ago, potentially adding some heterogeneity. And yes, in some older patients, a bone marrow biopsy wasn’t always done, which is a standard diagnostic tool. However, the study authors argue that persistent monocytosis in the blood is the most crucial diagnostic feature, and recent work suggests genetic data from blood can be highly accurate even without a bone marrow biopsy.

The Big Picture: Personalized Medicine

What’s the takeaway from all this? Well, it reinforces that NRAS mutation isn’t just a random genetic blip in CMML. It’s a significant factor associated with a more proliferative phenotype (higher WBC, more blasts), lower platelets, and importantly, worse overall and AML-free survival. The fact that these findings were validated in two independent, large cohorts – one national and one international – makes them much more robust and reliable.

This kind of research, leveraging big data from multiple sources, is crucial as healthcare shifts towards a more patient-centered, personalized approach. Understanding the specific genetic landscape of a patient’s CMML, like knowing if they have an NRAS mutation, can help doctors make more informed decisions about prognosis and potentially guide treatment strategies in the future. It’s all about using the incredible amount of data we can now collect to get a clearer picture of each individual patient’s disease and offer them the most precise care possible.

Source: Springer