Unlocking Cancer’s Secrets with Tiny Antibodies: A Novel VHH for Imaging and Therapy

Our Quest for Better Cancer Tools

We’re always on the lookout for smarter ways to tackle cancer. One of the big challenges is finding the cancer cells specifically, both for spotting them early and for delivering treatments right where they’re needed. Think of it like a targeted missile versus a scattershot approach. Non-invasive molecular imaging is a huge part of this – it lets us see what’s happening inside without cutting anyone open. While things like 18F-FDG scans are super common, they don’t always tell us *exactly* what’s going on at the molecular level, especially when we’re using targeted therapies. So, we really need more specific tools.

Conventional antibodies have been fantastic for this because they’re great at finding specific targets, like proteins that are overly abundant on cancer cells. They’re pretty specific and don’t cause much toxicity on their own. But they’re also quite large molecules. This means they hang around in the bloodstream for a while, which requires using radioisotopes that last a long time, leading to more radiation exposure. Plus, getting these big antibodies deep into solid tumors can be tricky.

Enter the VHHs: Tiny Powerhouses

This is where VHHs, or variable domains of heavy-chain only antibodies, come into the picture. Imagine taking just the essential, target-binding part of an antibody – that’s kind of what a VHH is. They’re much, much smaller than conventional antibodies. And because they’re so small, they have some really cool advantages. They can potentially penetrate deeper into solid tumors and clear out of the bloodstream much faster. This means we could use radioisotopes that have shorter half-lives, reducing radiation exposure and getting clearer images sooner. VHHs are already showing a lot of promise in both imaging and therapy, including as the targeting component for delivering potent drugs directly to cancer cells, like in Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs). The idea is to combine the antibody’s ability to find the target with a powerful drug that can kill the cell once it gets there. For this to work well, the targeting part needs to be specific, bind strongly, be stable, and ideally, get taken *inside* the cell.

Our Target: CEACAM5

We decided to focus on a protein called CEACAM5. It’s a highly glycosylated protein that was first identified way back in 1965 in colon cancer. What makes it interesting is that it’s found in high amounts on the surface of cells in lots of different epithelial cancers, including colon, stomach, lung, pancreatic, and cervical cancers. CEACAM5 helps cells stick together and communicate, but when it’s overexpressed in cancer, it can actually help tumors grow and spread. It’s been looked at as a potential target for imaging before, but we wanted to see if we could develop a VHH specifically against it that had the right properties for both imaging and therapy.

Developing Our Novel VHH: Meet 6B11

So, we set out to develop some new anti-CEACAM5 VHHs. We started by immunizing llamas (yes, llamas!) with human CEACAM5 to generate a library of potential VHHs. From that library, we selected 11 candidates and put them through their paces. We tested their ability to bind to cancer cells with different levels of CEACAM5 expression. After a lot of testing using techniques like ELISA, FACS, and immunofluorescence, two candidates, 6B11 and 6F8, stood out. 6B11 showed particularly high binding affinity and specificity. We confirmed that it really stuck to cells that had lots of CEACAM5 and didn’t stick to cells that didn’t.

We then scaled up production of 6B11 using an E. coli system to get enough material for more experiments. Our in-house produced 6B11 maintained its high affinity and specificity. We even confirmed its molecular weight – it’s indeed a tiny molecule!

Seeing is Believing: Imaging with 6B11

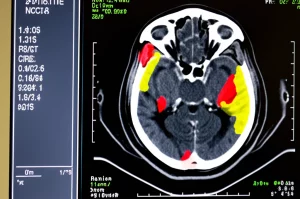

One of the big potential uses for 6B11 is in cancer imaging, specifically SPECT imaging. To test this, we labeled 6B11 with a radioisotope called 99mTc. The labeling process worked well, and the resulting 99mTc-6B11 still bound specifically to CEACAM5-positive cells in lab tests.

Then came the exciting part: testing it in living subjects. We used mice that had two tumors – one with high CEACAM5 expression and one where CEACAM5 was knocked out. We injected the 99mTc-6B11 and used SPECT/CT imaging to see where it went over time.

And guess what? The images showed that 99mTc-6B11 specifically accumulated in the tumors that had high CEACAM5 expression! The signal in the CEACAM5-positive tumors was significantly higher than in the knockout tumors, especially at later time points (4 and 24 hours post-injection). We also looked at the tumor-to-blood ratio, which is a key indicator of how well the imaging agent is targeting the tumor compared to just circulating in the blood. This ratio increased over time in the CEACAM5-positive tumors, while it stayed low in the knockout tumors.

We confirmed these findings by taking the tissues out after imaging and measuring the radioactivity (gamma counting) and looking at slices of the tumors (autoradiography and immunohistochemistry). Everything lined up – the 99mTc-6B11 was definitely concentrating where the CEACAM5 was.

A typical feature of VHHs is that they clear out of the body very quickly, mainly through the kidneys, because they’re so small. Our results confirmed this – we saw high uptake in the kidneys and bladder. While fast clearance is great for reducing background signal and getting images sooner, high kidney uptake is something we need to be mindful of for potential kidney toxicity, especially with therapeutic radioisotopes. We also saw some uptake in the liver and spleen, which might be related to the specific radioisotope we used.

Overall, this study showed that our novel anti-CEACAM5 VHH, 6B11, works really well as a diagnostic tool for visualizing CEACAM5-positive cancers using SPECT imaging. To our knowledge, this is the first anti-CEACAM5 VHH shown to have specific tumor uptake *in vivo*.

Beyond Imaging: Potential for Therapy

Okay, so 6B11 is great for finding tumors. But what about treating them? We first tested if the “naked” VHHs (6B11 and 6F8, without any drug attached) had any direct anti-cancer effects in lab dishes. We looked at cell viability, migration, and adhesion. Unfortunately, neither 6B11 nor 6F8 significantly inhibited cancer cell growth or movement on their own in these *in vitro* tests.

But don’t despair! Remember the idea of VHH-drug conjugates? For a VHH to be a good carrier for a drug, it needs to bind to the target and then ideally get taken *inside* the cancer cell. This process is called internalization. Once inside, if the drug is released in the right place (like the lysosomes, which are like the cell’s recycling centers), it can do its job killing the cell.

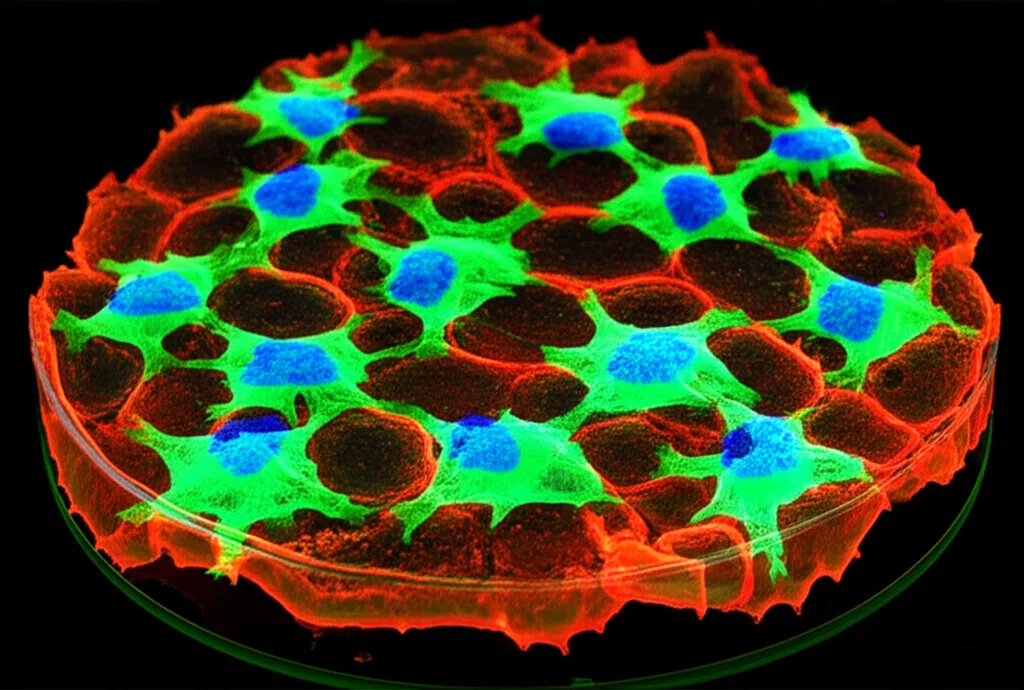

To test this, we labeled 6B11 with a fluorescent dye called Oregon Green 488 (OG488-6B11) and watched what happened when we added it to cancer cells. We saw that OG488-6B11 was effectively taken *inside* the CEACAM5-positive cells, and this increased over time. Even better, we saw that the fluorescent signal ended up co-localizing with lysosomes. This is fantastic news because it means 6B11 has the right properties to deliver a drug payload directly into the cell’s machinery where it can be released and get to work.

We also looked at how well the labeled VHH could penetrate 3D tumor spheroids (which are more like real tumors than flat layers of cells). We compared OG488-6B11 to a conventional anti-CEACAM5 antibody labeled with a similar fluorescent dye. The results were striking! While the conventional antibody mostly stayed on the outside of the spheroid, the OG488-6B11 penetrated deep into the center within 24 hours. This confirms that the small size of VHHs gives them a real advantage in getting into solid tumors, which is a major hurdle for conventional ADCs.

So, even though 6B11 didn’t kill cancer cells on its own in our initial tests, its ability to specifically target, penetrate tumors, and get internalized into lysosomes makes it a really promising candidate for developing VHH-based drug conjugates.

What’s Next? Refining Our Tiny Tool

While we’re really excited about 6B11’s potential, there’s always room for improvement. We saw that it clears out of the blood very quickly, which is good for imaging timing but might mean less of it gets to the tumor overall. Scientists are exploring ways to improve VHH pharmacokinetics, like attaching them to things that extend their time in the blood, such as albumin-binding domains, or modifying the tumor environment. Fusing a VHH with an albumin-binding domain has shown great promise in other studies, significantly extending the VHH’s half-life in the blood and increasing tumor uptake while still allowing for good tissue penetration.

We also need to consider potential immunogenicity – basically, could the body see our VHH as foreign and react against it? The way we produced and labeled 6B11 in this study involved elements (like a His-tag and the specific labeling chemistry) that aren’t ideal for human use. Future work will involve refining the production and labeling methods, perhaps removing the His-tag or using different ways to attach radioisotopes or drugs. Humanizing the VHH sequence could also help reduce the risk of an immune response.

Finally, while our *in vitro* tests didn’t show direct anti-cancer effects of the naked VHH, cancer is complex. The tumor microenvironment plays a huge role. It’s possible that in more complex models, like organoids, co-cultures with immune cells, or *in vivo* studies, 6B11 might show different effects, perhaps by influencing cell-cell interactions or immune responses. This warrants further investigation.

Wrapping It Up

In a nutshell, we’ve successfully developed a novel anti-CEACAM5 VHH, 6B11, that shows high specificity and affinity for its target. We’ve demonstrated its potential as a diagnostic tool for CEACAM5-positive cancers using SPECT imaging, showing specific tumor uptake and fast clearance. Crucially, we’ve also shown that it can penetrate deep into tumor models and get internalized into cancer cells and delivered to lysosomes, making it a strong candidate for use as a targeting component in VHH-based drug conjugates for cancer therapy. There are still steps to take to optimize it, particularly regarding pharmacokinetics and potential immunogenicity, but this study represents a significant step forward in developing these tiny, powerful antibodies for fighting cancer.

Source: Springer

![Immagine fotorealistica di una scansione PET cerebrale che mostra l'attività della P-glicoproteina alla barriera emato-encefalica, con il tracciante [18F]MC225 evidenziato, obiettivo 50mm, alta definizione, illuminazione drammatica per enfatizzare i dettagli scientifici.](https://scienzachiara.it/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/043_immagine-fotorealistica-di-una-scansione-pet-cerebrale-che-mostra-lattivita-della-p-glicoproteina-alla-barriera-emato-encefalica-con-il-274x300.webp)