Cracking the Code: A Rwandan Family, Atypical CdLS, and a Brand-New Gene Clue!

Hey there, science enthusiasts! Ever heard of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome, or CdLS? It’s one of those super rare genetic conditions that can be a real puzzle for doctors and families. Imagine a syndrome with a whole spectrum of signs – from developmental delays and unique facial features to limb differences and hearing issues. What’s even trickier is that for about 30% of folks who look like they have CdLS, the exact genetic culprit remains a mystery. This is especially true in places with fewer resources, like many parts of Africa.

Well, I’m thrilled to share some exciting news about a recent breakthrough! We got to dive deep into the genetics of a Rwandan family where two siblings were showing some, but not all, of the classic signs of CdLS. It’s what we call an “atypical” presentation, and it really makes you put on your detective hat.

Meet the Family: A Unique Presentation

Our story centers on a family from Rwanda: two parents and their two children, a 17-year-old daughter and a 14-year-old son. Both kids were initially referred because of hearing impairment. The daughter had profound hearing loss in both ears, some moderate hypertelorism (that’s when the eyes are spaced a bit wider apart), progressive vision problems, and secondary amenorrhea (meaning her periods had stopped). Her younger brother also had profound bilateral hearing loss and intellectual disability, but interestingly, he didn’t have the noticeable facial dysmorphism often seen in CdLS. The parents, thankfully, were healthy.

This wasn’t your textbook CdLS, which made it all the more intriguing. We knew we had to look closer at their genetic makeup.

The Genetic Hunt: Exome Sequencing to the Rescue!

So, how do you find a tiny, elusive change in a massive genetic instruction book? We turned to a powerful tool called Exome Sequencing (ES). Think of it like this: your DNA has tons of information, but the exome is the part that contains the actual recipes (genes) for making proteins. ES lets us read through these recipes to spot any “typos” or variations.

We took DNA samples from the two affected siblings and their parents. After preparing the DNA and running it through the sequencer, we meticulously analyzed the data. We were looking for rare genetic variants that could explain the siblings’ conditions, especially focusing on an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. This means both parents would carry one copy of the variant (and be unaffected), and the children would need to inherit two copies (one from each parent) to show the condition.

And bingo! We found something really interesting: a novel homozygous missense variant in a gene called TRMT61A. The specific change was NM_152307.3:c.665C > T, leading to an amino acid change p.(Ala222Val). Both siblings had two copies of this variant, and both parents were heterozygous carriers, meaning they each had one copy. This was a perfect fit for the family pattern!

To be extra sure, we validated this finding using Sanger sequencing, the gold standard for confirming specific DNA changes. And guess what? This particular variant wasn’t found in 100 healthy control individuals from Rwanda, making it even more likely to be the cause.

What Does This TRMT61A Variant Actually Do?

Finding a variant is one thing; understanding if it’s truly pathogenic (disease-causing) is another. So, we rolled up our sleeves for some more detective work!

- In Silico Predictions: We used a bunch of cool computer programs (like PolyPhen-2, SIFT, and MutationTaster) that predict how damaging a genetic change might be to the protein. The consensus? This variant looked pretty suspicious, likely to be damaging. The alanine at position 222 is super conserved across different species, meaning it hasn’t changed much throughout evolution – a big hint that it’s important!

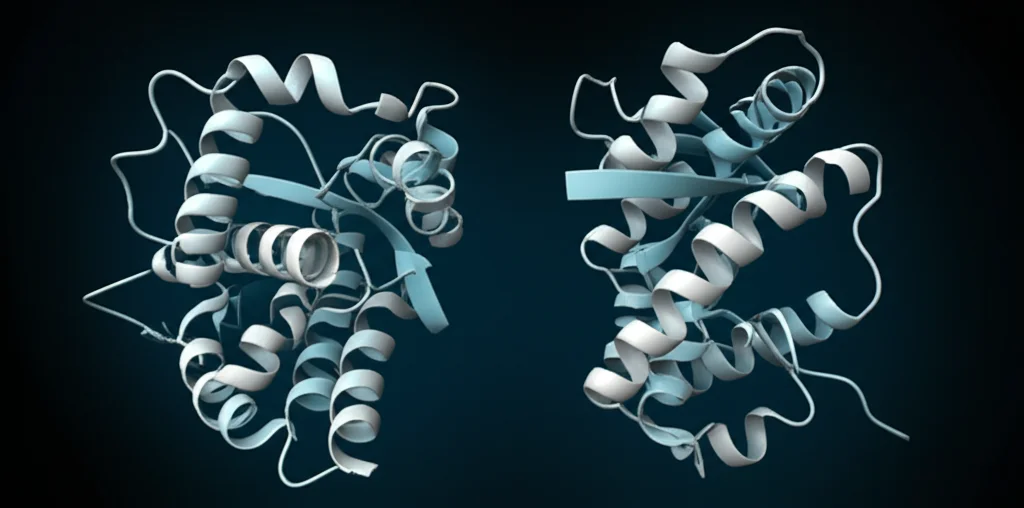

- Protein Modelling: We then tried to see what this change might do to the 3D structure of the TRMT61A protein. Our 2-D modelling suggested that the p.(Ala222Val) change could significantly decrease the protein’s stability. While the 3D model didn’t show massive structural shifts, stability is key for a protein to do its job right.

- Cell-Based Experiments: This is where things got really hands-on. We used HEK293T cells (a common cell line in labs) to see how the mutant TRMT61A protein behaved compared to the normal, wild-type version. We tagged the proteins with a green fluorescent marker (tGFP) to watch them under a confocal microscope.

The results were striking! The normal TRMT61A protein was found in both the nucleus (the cell’s control center) and the cytoplasm (the rest of the cell), which is where it’s expected to be. But the mutant protein? It seemed to accumulate mainly in the nucleus. Plus, the fluorescence signal from the mutant protein was lower, and western blot analysis (a technique to measure protein levels) confirmed that there was less of the mutant protein being made or it was less stable. This mislocalization and potential reduction in protein could seriously mess with its functions in both the mitochondria (the cell’s powerhouses) and the cytosol.

So, putting all this evidence together – the family segregation, the rarity of the variant, the in silico predictions, and the functional data from cell experiments – we classified this TRMT61A variant as likely pathogenic. It strongly suggests a causal link to the atypical CdLS phenotypes we saw in the siblings.

Atypical CdLS: Expanding the Spectrum

It’s important to remember that these Rwandan siblings didn’t have many of the classic CdLS features like major growth delays, hirsutism (excessive hair growth), or the really distinct facial characteristics. However, they did have features that are seen in CdLS, such as profound hearing impairment (both siblings), intellectual disability and low-set ears (brother), and arched/thick eyebrows, hypertelorism, vision loss, and secondary amenorrhea (sister).

This is super interesting because it broadens what we understand as TRMT61A-related CdLS. Before our study, there was only one other report globally linking TRMT61A to CdLS – a study from 2020 describing two Palestinian sisters. Those sisters had a more typical CdLS presentation, with craniofacial abnormalities, growth and cognitive issues, and limb anomalies. They had compound heterozygous variants in TRMT61A, also following an autosomal recessive pattern.

Our Rwandan family is now the second instance worldwide and the first from Africa to have CdLS associated with likely pathogenic variants in TRMT61A. This highlights that the same gene can sometimes lead to a wider range of symptoms than initially thought.

What’s TRMT61A‘s Day Job Anyway?

You might be wondering what TRMT61A actually does. This gene codes for an enzyme called tRNA-methyltransferase. Its job is crucial: it helps modify transfer RNA (tRNA), which are essential molecules involved in building proteins. Specifically, TRMT61A (working with another protein called TRMT6) adds a little chemical tag (a methyl group) to a specific spot on initiator methionyl-tRNA. This modification, m1A58, is important for the tRNA to work correctly.

Defects in tRNA modification processes have been linked to a whole host of human diseases, including cancer, type 2 diabetes, neurological disorders, and mitochondrial problems. So, it’s clear that genes like TRMT61A are vital for our cells to function properly.

While we’re still figuring out the exact connection between TRMT61A and the more well-known CdLS genes (like NIPBL or SMC1A, which are involved in cohesin function – a complex that helps manage DNA structure), it’s known that TRMT61A can be misregulated when these major CdLS genes are mutated. Plus, both TRMT61A and NIPBL play roles in gene expression and genome stability, which could be a shared pathway leading to CdLS-like features.

Why This Discovery Matters

This study is a big deal for a few reasons. Firstly, we’ve identified a novel biallelic variant in TRMT61A associated with an atypical form of CdLS. This expands the genetic landscape of this rare syndrome.

Secondly, it’s the first such report from Africa. Genetic studies in African populations are incredibly important because Africa holds the greatest human genetic diversity. Understanding this diversity is key to diagnosing and eventually treating genetic conditions for everyone, everywhere. Often, genetic databases are skewed towards European populations, which can make diagnosing conditions in people of other ancestries much harder.

This work really underscores the need to make advanced genetic tools like Exome Sequencing more widely available, especially for characterizing rare diseases in understudied populations. Every family, every new genetic finding, helps us piece together the complex puzzle of human health.

It’s a reminder that even when a condition doesn’t fit the “classic” description, digging deeper with modern genetics can uncover answers and provide families with a diagnosis, which is often the first step towards understanding and support.

We’re excited to see how this finding contributes to the broader understanding of CdLS and the role of TRMT61A. And who knows? Maybe it will pave the way for more discoveries in the wonderfully diverse genetic landscape of Africa!

Source: Springer