Mapping Nitinol’s Future: TTT, TTS, and Perfecting Medical Devices

Hey there! Ever tinkered with something that seems almost magical? Something that can remember its shape or stretch like crazy and snap back? If you’re in the world of advanced materials, you’ve probably bumped into Nitinol. It’s this fantastic nickel-titanium alloy, super popular in medical devices because of its unique shape memory and superelastic properties.

But here’s the kicker: getting a Nitinol component into the perfect shape *and* making sure it behaves exactly how you need it to – hitting those sweet spot transformation temperatures and having the right mechanical oomph – is anything but simple. It’s a bit like baking a very finicky cake; the time and temperature you use to set the shape also mess with the material’s internal structure. We’re talking about tiny nickel-rich bits forming or dissolving, and the material’s internal stress getting rearranged. This whole dance makes finding the right recipe feel less like science and more like guesswork sometimes.

The Tools of the Trade: TTT and TTS Diagrams

Traditionally, folks have used Time–Temperature–Transformation (TTT) diagrams to map out how heat treatment affects those crucial transformation temperatures (like when it changes phase from martensite to austenite, or vice versa). Think of a TTT diagram as a map showing you, for a given material, what transformation temperatures you’ll get if you heat it to a certain temperature for a certain amount of time.

What’s been a bit less common, though, are Time–Temperature–Stress (TTS) diagrams. These are super helpful because they show how that same heat treatment impacts the mechanical properties – things like the upper and lower plateau stresses (basically, how much force it takes to stretch it superelastically) or its overall strength.

Lots of smart people have done great work on this before, creating TTT or TTS diagrams for specific types or compositions of Nitinol. But honestly, there wasn’t a really broad, comprehensive look that tied *all* these variables together across different materials and forms.

Our Grand Experiment: A Deep Dive into Nitinol Recipes

So, we decided to roll up our sleeves and take a seriously wide-ranging look. Our goal? To give designers a more solid framework, a kind of cheat sheet, to help them nail down the right properties without endless trial and error. We explored how a bunch of things influence both the transformation temperatures *and* the mechanical properties:

- Chemical Composition: Does slightly more nickel (Ni50.8Ti) versus slightly less (Ni50.6Ti) make a difference?

- Material Format: Are we talking about wire or tube? They behave differently!

- Starting Point: Was the material already straightened, or was it “as-drawn” (fresh off the drawing process)?

We also peeked into something super common in complex designs: multi-step heat treatments. Sometimes you can’t get the shape you need in one go, so you heat it, bend it a bit, cool it, then heat it again, maybe at a different temperature or for a different time. How does that stack up?

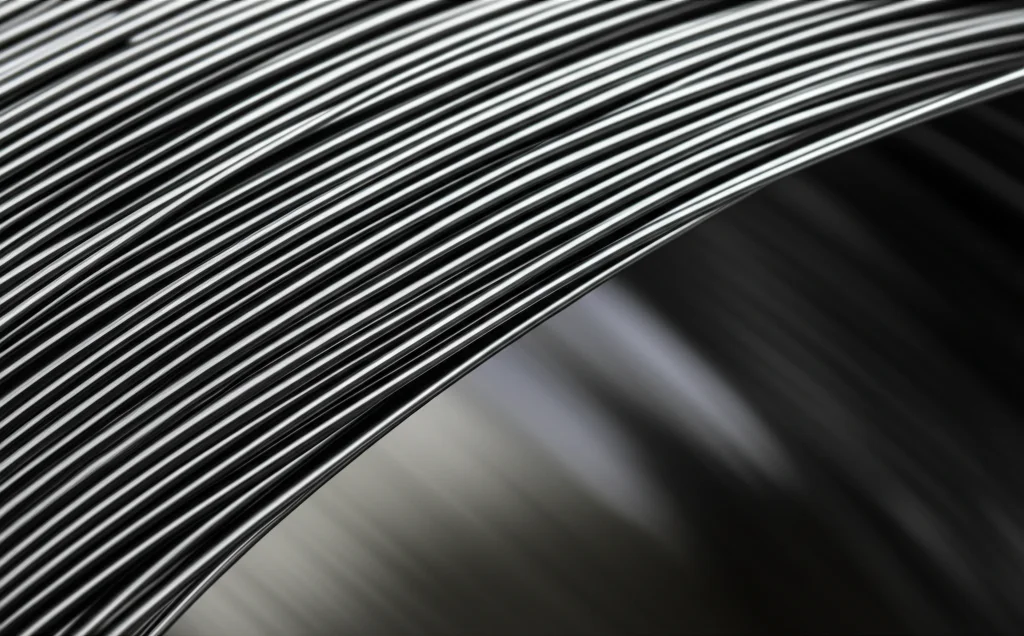

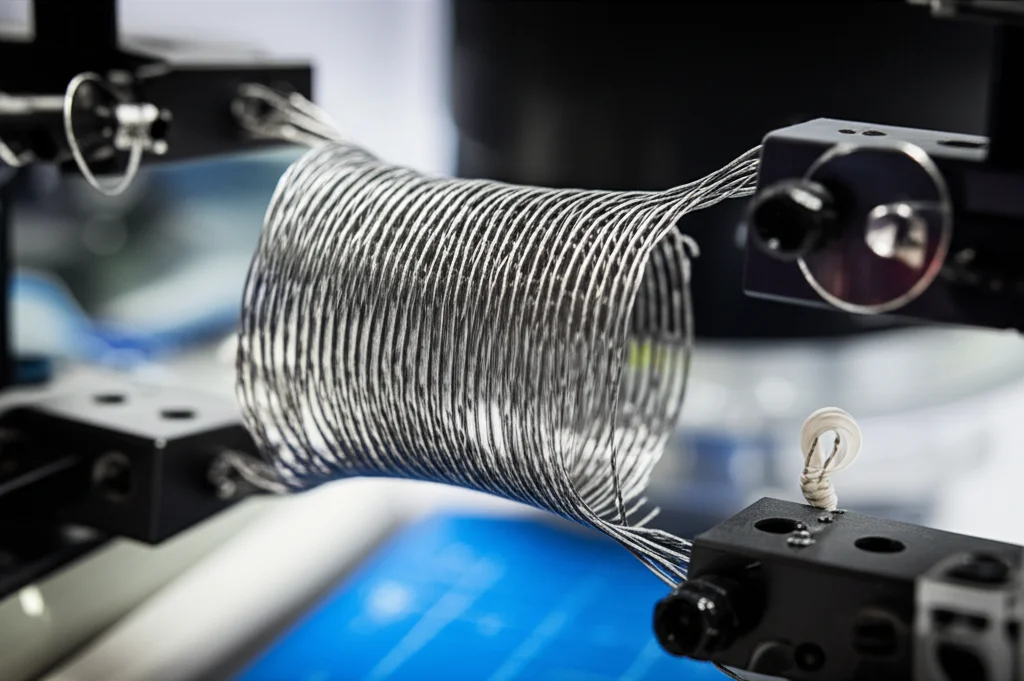

We manufactured tons of samples – wires and tubes – and put them through a dizzying array of heat treatments. We varied the time (from just 1 minute up to 120 minutes) and temperature (from 250°C to 600°C, depending on the material and method). We even used different heating methods: a regular air furnace for wires and a molten salt bath for tubes (which heats things up faster and more evenly).

After the heat treatments, we threw everything we had at these samples to see how they changed. We used Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to precisely measure the transformation temperatures. We did Bend and Free Recovery (BFR) tests, especially on wires, which is another way to check transformation temperatures. And crucially, we did tensile testing to measure those plateau stresses (UPS and LPS) and radial force testing on tube samples shaped like small stents to see how they’d perform under more real-world conditions.

The Wire Story: Chemistry’s Subtle Hand

First up, the wires. We took two batches of wire, identical in how they were drawn but with slightly different nickel content (Wire A had a smidge more nickel than Wire B). We heat-treated them in an air furnace across a range of times and temperatures.

Get this: the TTT diagrams for these two wires looked *remarkably* similar. You’d think that slight difference in chemistry would show up big time, but for transformation temperatures, the map was almost the same, especially in the common shape-setting zones. There were some small differences at very short times and low temperatures, which is interesting for fine-tuning, but broadly, the TTT maps were twins.

However, when we looked at the TTS diagrams – the stress maps – things got interesting. While the lower plateau stress (LPS) was pretty similar between the two wires, the upper plateau stress (UPS) diverged, particularly at longer and hotter heat treatments. Wire B (with slightly less nickel) showed a higher UPS in these conditions. This tells us that while the transformation *temperatures* might be similar, the mechanical *strength* can still be influenced by that initial chemistry difference, likely due to how those tiny nickel-rich precipitates form.

The Tube Saga: Vendor Variability is Real!

Next, the tubes. This is where things got really eye-opening. We sourced tubes built to the *exact same specification* from two different manufacturers, using material from the same initial ingot supplier. Both were certified to have a specific austenite finish (Af) temperature using the BFR test.

But when we tested them with DSC *before* any heat treatment, they were wildly different! Tube A had a two-step transformation and an Af of +19°C, while Tube B had a single-step transformation and an Af of -17°C. That’s a huge difference – about 35°C! And their initial mechanical properties were different too, with Tube B having about 10% higher plateau stresses. This immediately flags a potential issue: relying *only* on a standard BFR spec might not tell you the whole story about the material you’re getting.

Here’s another twist: after we heat-treated these tubes in a salt bath using various recipes, their transformation temperatures became surprisingly similar, especially in typical manufacturing ranges. Regardless of whether they started with a two-step or one-step transformation, the heat treatment often *promoted* a two-step transformation (including the R-phase). So, the heat treatment recipe seemed to override the initial differences in transformation behavior, bringing their TTT maps into alignment.

But just like with the wires, the TTS diagrams told a different story. Even though the heat-treated tubes had comparable Af temperatures, their mechanical properties were substantially different. Tube B, which started with higher stresses, consistently showed *lower* plateau stresses (10-25% lower!) after heat treatment compared to Tube A. This is a massive finding: you can take two tubes that meet the same spec, put them through the *exact same* heat treatment, end up with components that have the *same* transformation temperature, but they will behave *very differently* mechanically.

The Multi-Step Maze: Not Just Adding Time

Many complex Nitinol parts need multiple shape-setting steps. We looked at doing this in stages (1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 steps) at constant time/temperature per step. Unsurprisingly, both the Af and R’f temperatures generally increased with more steps.

We also wondered if you could just predict the outcome of a multi-step process by simply adding up the total time at temperature from a single-step diagram. Turns out, nope! For some combinations, it was close, but for others, the results were quite different. This mismatch is likely due to things like how quickly the part heats up in each step and the complex, non-linear way that precipitates and dislocations form or disappear over time and temperature.

Why Af Isn’t the Whole Story (Especially for Stents)

This brings us to perhaps the most critical takeaway, especially for medical devices like stents. Imagine you have a component specification that says the part *must* have an Af temperature of, say, 25°C ± 3°C. Our study showed you could achieve this target Af using different heat treatment recipes and even with tubes from different suppliers (Tube A and Tube B).

We took stent-like rings made from Tube A and Tube B, heat-treated them with two different multi-step recipes that both resulted in the target 25°C Af. We then tested their mechanical performance.

In one recipe, the simple uniaxial tensile properties (UPS, LPS) were nearly identical between Tube A and B. In the other recipe, Tube A had significantly higher plateau stresses. But here’s the kicker: when we performed a radial force test (which simulates how a stent expands and pushes against a vessel wall – a much more relevant test for this application), Tube A consistently showed higher radial resistive force and chronic outward force compared to Tube B, *regardless* of whether the uniaxial tension tests matched or not!

This is huge. It means simply matching the component’s Af temperature, or even its basic uniaxial tensile properties, is *not* enough to guarantee consistent performance, especially in complex loading scenarios like a stent experiences. The material’s history and subtle differences from the supplier can still have a big impact on how the final device behaves.

A Peek Under the Hood (A Bit of Speculation)

Why do we see these differences? For the wires, the identical drawing process likely meant similar internal stress (dislocation density), so the differences in mechanical properties probably come down to how that slightly different nickel content affects the formation of those tiny precipitates during heat treatment.

For the tubes, since they had the same chemistry but came from different vendors, their initial differences in mechanical properties and transformation behavior likely stem from the vendors’ proprietary drawing processes and initial straightening heat treatments, which would leave them with different levels of internal stress and precipitate structures *before* we even started our experiments.

And for the stents, the radial force test is much more complex than a simple pull test. It involves bending and compression, and Nitinol’s behavior in compression isn’t always a simple reflection of its behavior in tension. These differences in compression behavior between the tubes, not fully captured by standard tests, likely explain why the radial force differed even when Af and uniaxial tension seemed matched.

Putting it All Together: Maps, Materials, and Medical Devices

So, what did we learn from this deep dive?

- BFR tests for transformation temperature seem to align more with the R-phase finish temperature (R’f) from DSC, not necessarily the main austenite finish (Af).

- Just hitting a target Af temperature isn’t enough to guarantee consistent mechanical performance, especially when using materials from different suppliers or with different histories.

- The starting material matters! Even with the same chemistry, how the wire or tube was processed beforehand (drawing, initial heat treatments) significantly impacts the final mechanical properties after shape setting.

- Tube suppliers, even when meeting the same standard specs (like BFR Af), can provide materials with very different starting transformation behavior (seen by DSC) and significantly different mechanical responses to subsequent heat treatment.

- Multi-step heat treatments don’t simply add up; their outcome can be complex and not easily predicted from single-step data.

- Most importantly: For critical applications like medical devices, relying *only* on Af or simple uniaxial tension tests isn’t sufficient. You need to look at more relevant mechanical tests (like radial force for stents) and understand the material’s full TTT and TTS landscape to ensure consistent component performance, especially if you’re considering swapping material suppliers.

While our study used a single batch from each source (so there might be some lot-to-lot variation we didn’t capture) and didn’t cover every possible heat treatment method or tooling effect, the hundreds of data points we compiled allowed us to build some seriously useful TTT and TTS maps. These maps clearly show that while transformation temperatures can often be tuned to a target, the mechanical properties are much more sensitive to the material’s origin and history.

The big takeaway? Designing with Nitinol requires more than just hitting a temperature target. You need the full picture – the TTT *and* the TTS diagrams – and you need to understand how your material’s specific pedigree influences its entire post-shape-setting behavior. It’s about using the right maps to navigate the complex world of Nitinol properties and ensure those critical medical devices perform exactly as intended.

Source: Springer