Screw It! A Better Way to Fix Tricky Femoral Neck Fractures

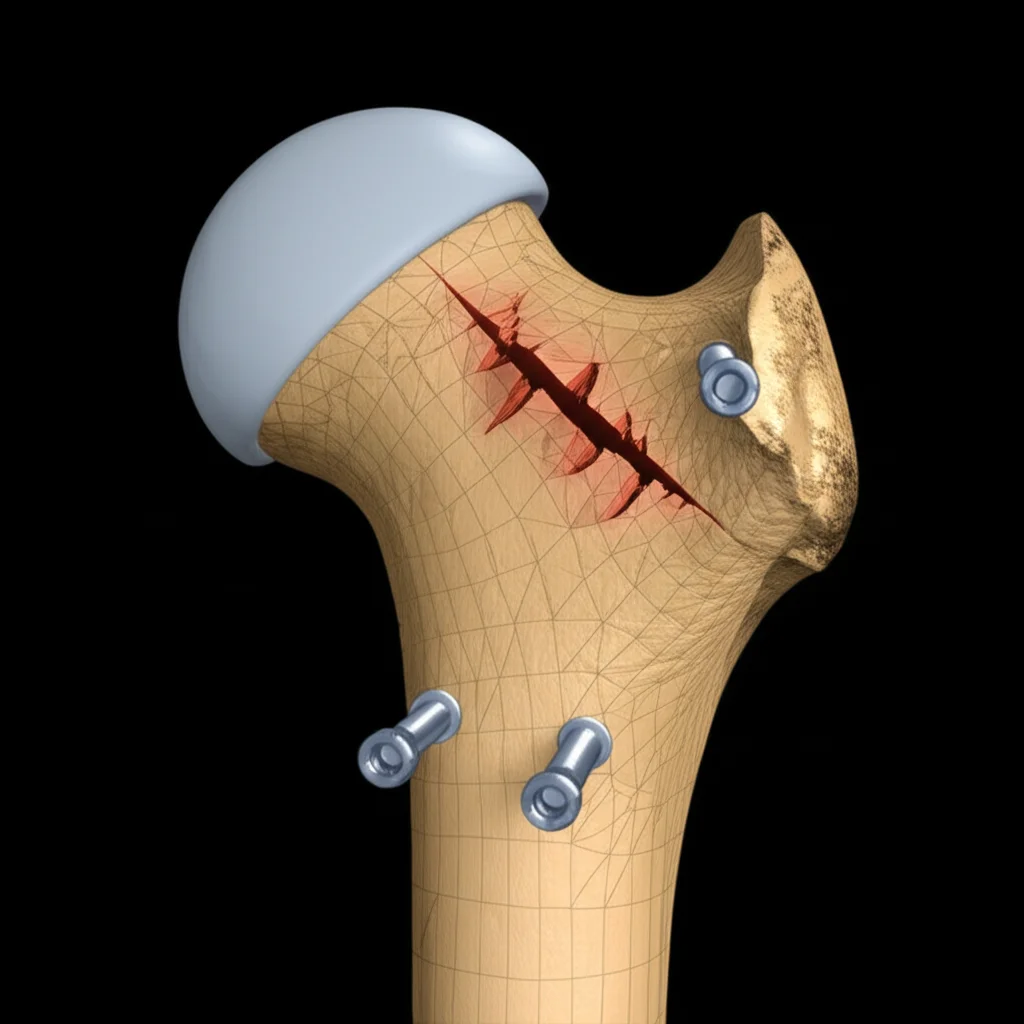

Hey there! Let’s dive into something a bit technical but super important: broken hips. Specifically, those really nasty ones called Pauwels type III femoral neck fractures. If you’ve ever heard about hip fractures, you know they’re no fun, and this type is particularly tricky.

The Problem with Pauwels Type III Fractures

So, what’s the deal with these Pauwels type III fractures? Well, imagine your femoral neck (that’s the part connecting your hip bone to the long thigh bone) breaks at a really steep angle, over 50 degrees. This high angle means there’s a huge amount of *shear force* trying to slide the broken pieces past each other. Think of it like trying to hold two slippery slopes together – tough job!

These fractures are common in younger, active folks after serious accidents. And because of that crazy shear force, they’re super unstable. This instability leads to big problems like the bone not healing properly (nonunion) or the blood supply getting messed up, causing part of the bone to die (femoral head necrosis). The stats are pretty grim, with nonunion rates sometimes hitting nearly 60% and necrosis up to 86%! Yikes.

Trying to Hold Things Together: The Usual Suspects

For years, the go-to method has been using three cannulated compression screws (3CCS). They’re like big screws designed to squeeze the bone pieces together. And yeah, they work okay sometimes, but for these high-angle, high-shear fractures, their stability is, shall we say, *controversial*. They just can’t always fight off that sliding force effectively.

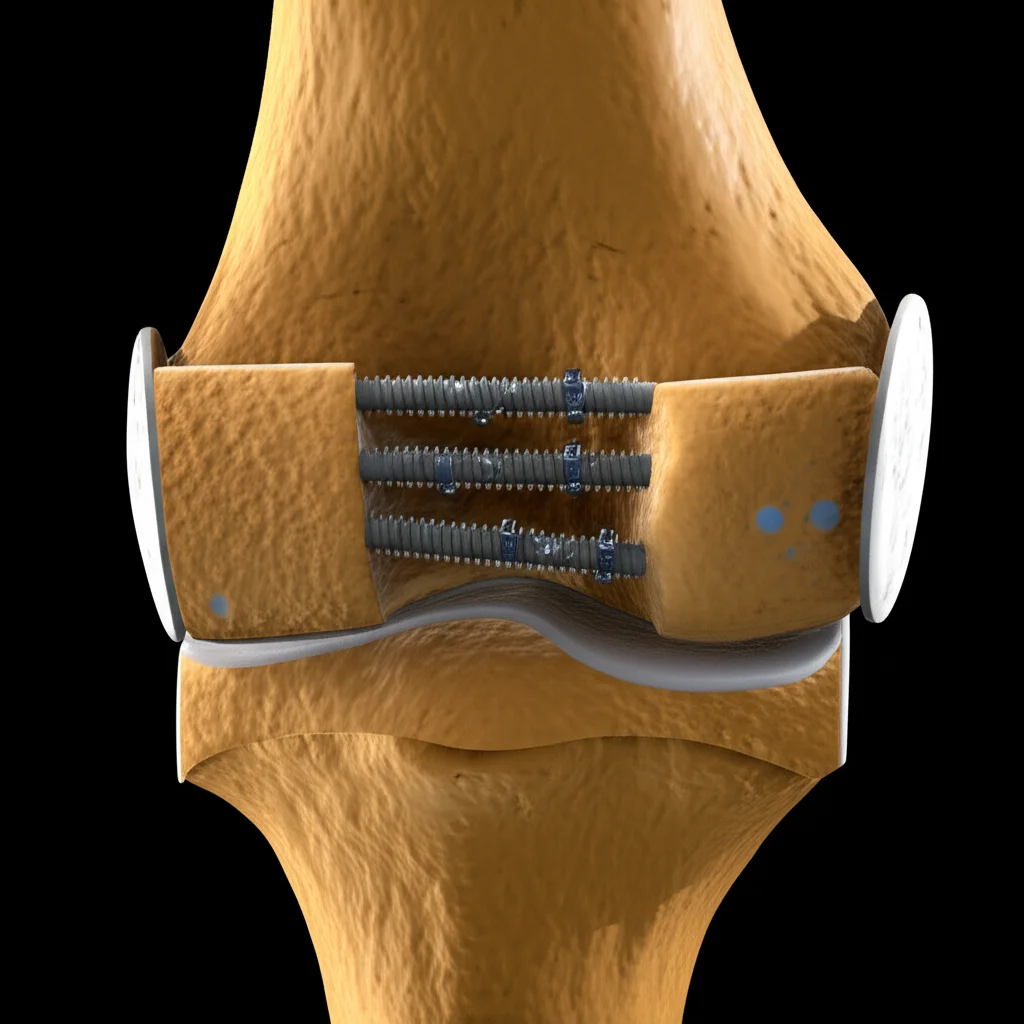

To try and beef things up, some surgeons add a medial buttress locking plate (BL) along with the 3CCS. This plate is like adding a strong splint on the inside. It *does* seem to improve stability in some cases. But, and it’s a big but, it means a bigger surgery, more trauma to the area (potentially messing with that crucial blood supply even more!), longer time under anesthesia, and a higher risk of complications. Not ideal for everyone, and it’s limited its widespread use.

Our team also explored adding a horizontal screw (HS) to the 3CCS setup, thinking it might help counteract the shear. But honestly, the clinical results have been debated. It seems like it might not be enough to make a significant difference against those powerful forces.

A New Contender: The Obstructing Screw (OS)

So, the big challenge is finding a way to get *mechanical stability* without causing *too much biological damage* (like cutting off blood supply). This is where a new idea comes in: adding an antishear obstructing screw (OS) to the standard 3CCS setup.

The concept is pretty clever. You put this extra screw in a specific spot near the fracture line on the inside of the femur. The screw head sits just above the fracture line. As that nasty shear force tries to slide the bone, the OS gets in the way – it *obstructs* the movement. This action actually *converts* the shear force into compressive stress, which is exactly what you want for bone healing! It provides continuous pressure on the fracture ends. It sounds promising, right? But before trying it widely in people, you need to test it out.

Putting it to the Test: Virtual Bone Engineering

This is where Finite Element Analysis (FEA) comes in. It’s a fancy computer simulation method used a lot in engineering (think testing how a bridge holds up) and now in medical research. You can build a detailed 3D model of a bone, add screws, simulate a fracture, and then apply forces to see what happens – where the stress goes, how much it moves, how stiff the whole setup is. It’s like a virtual test lab!

For this study, we took CT scans from a healthy 30-year-old guy (thanks, volunteer!) to build a super realistic 3D model of a femur. Then, we virtually “broke” the femoral neck at a high angle (like a Pauwels type III fracture, specifically modeled at over 70 degrees).

We designed four different screw setups on this virtual bone:

- Group 1: Just the three cannulated compression screws (3CCS). The baseline.

- Group 2: 3CCS plus the horizontal screw (3CCS + HS).

- Group 3: 3CCS plus the obstructing screw (3CCS + OS). The new idea!

- Group 4: 3CCS plus the medial buttress locking plate (3CCS + BL). The more invasive but potentially very stable option.

We applied a load simulating standing on one leg (about 2100 N, which is roughly three times the body weight for a 70kg person – because muscles add force!). Then, we crunched the numbers to see how each setup performed.

What the Virtual Test Showed: The Results Are In!

Okay, drumroll please… what did we find when we poked and prodded these virtual bones and screws?

First, we looked at *stress distribution*. Where does the force go? In the basic 3CCS group, the stress on the bone was pretty high (peak of 296.55 MPa). Adding the HS helped a bit, reducing it by about 13%. But adding the *OS*? Wow! The peak stress on the femur dropped dramatically by over 57% to just 126.49 MPa. This suggests the OS is doing a fantastic job of taking load and distributing it better. The BL group actually *increased* peak stress on the femur slightly compared to 3CCS, which is interesting.

Now, let’s talk about the *screws themselves*. If the screws are taking too much stress, they can break or fail. In the 3CCS group, one of the main screws (CCS #1) had a peak stress of 433.98 MPa. Adding the HS reduced this by about 18%. But in the 3CCS + OS group, the stress on the CCS screws plummeted! CCS #1 stress dropped by nearly 69%, CCS #2 by 68%, and CCS #3 by a massive 82%! This means the OS is really protecting the main screws. The BL was also great at reducing stress on the CCS screws (71-76% reduction), showing it offloads them effectively too.

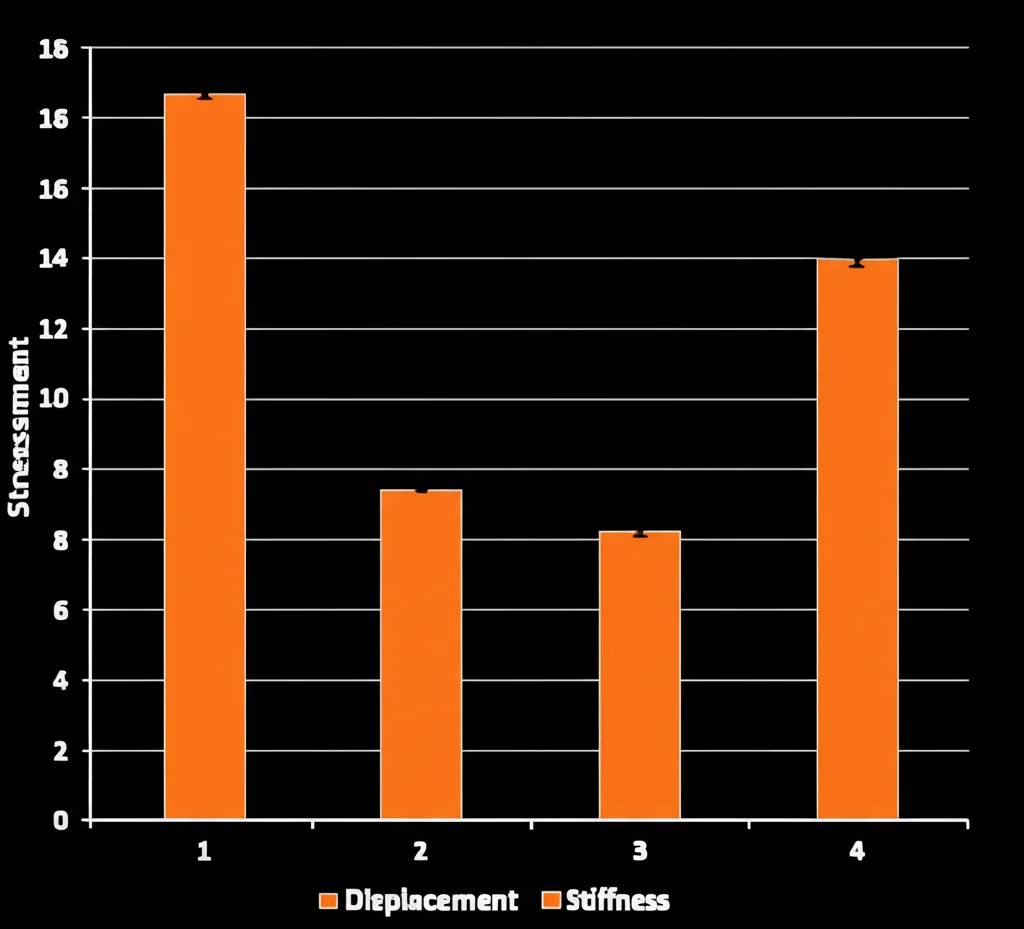

Next, we looked at *displacement*. How much do the bone pieces move? Less movement is better for healing. In the 3CCS group, the overall femur displacement was 4.76 mm, and the movement right at the fracture site was 1.53 mm. Adding the HS barely changed things (less than 2% improvement). But the OS group saw a significant improvement: overall displacement dropped by nearly 14% (to 4.11 mm), and fracture site displacement dropped by over 25% (to 1.14 mm). The BL group was the champion here, with the least displacement overall (3.79 mm, over 20% less than 3CCS) and at the fracture site (1.01 mm, nearly 34% less). So, BL is the most rigid, but OS is a strong second, much better than 3CCS or 3CCS+HS.

Finally, *stiffness*. How rigid is the whole bone-screw system? Higher stiffness means it resists deformation better under load. The 3CCS group had a stiffness of 441.18 N/mm. Adding HS only slightly increased it (less than 2%). But the OS group saw a big jump in stiffness, over 15% higher (510.95 N/mm). And you guessed it, the BL group was the stiffest of all, over 25% higher than 3CCS (554.09 N/mm).

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Based on this virtual testing, the combination of 3CCS and the antishear obstructing screw (OS) looks *really* promising for tackling those tough Pauwels type III femoral neck fractures.

Why? Because it offers significant *mechanical advantages*. It does a great job of:

- Balancing stress distribution in the bone.

- Dramatically reducing the stress on the main CCS screws, making them less likely to fail.

- Significantly limiting movement at the fracture site.

- Making the overall bone-screw structure much stiffer.

While the BL plate setup provided the *absolute best* mechanical stability in this simulation, its downsides in real life are significant – more invasive surgery, higher risk to blood supply, longer recovery. The OS method, on the other hand, seems to offer mechanical stability that’s second only to the BL, but with the potential for much *lower biological interference*. It’s a simpler operation, less invasive, and likely carries a lower risk of messing up that crucial blood flow to the femoral head.

Adding the horizontal screw didn’t really cut it compared to the OS or BL. It just didn’t provide a significant boost in stability.

But Let’s Be Real: Limitations Exist

Now, it’s important to remember this was a *finite element analysis*. It’s a powerful tool, but it has limitations.

- We assumed the bone material was uniform and behaved linearly, which isn’t perfectly true in real life. Bones are complex!

- The model was based on one specific person’s anatomy. Everyone’s bones are a bit different.

- We only simulated one specific fracture angle for Pauwels type III (over 70°). The OS might behave differently with slightly different angles.

- We only looked at a single-leg standing load. Real life involves twisting, bending, and varying forces.

- We didn’t compare it to *every* possible fixation method out there, like the dynamic hip screw, which is also used for these fractures.

These simplifications mean the results are theoretical and provide *support* for the idea, but they aren’t the final word.

The Bottom Line

Despite the limitations of the simulation, the findings are pretty compelling. The idea of using an obstructing screw alongside standard cannulated screws for high-angle femoral neck fractures shows significant mechanical promise. It seems to offer a sweet spot: much better stability than standard screws alone or with a horizontal screw, and stability approaching that of a buttress plate, but with potentially less surgical trauma and risk to the bone’s blood supply.

It’s simple to do, minimally invasive, and could lead to fewer complications like nonunion or necrosis. This virtual study suggests the 3CCS + OS method has great potential for clinical use and is definitely worth exploring further in real-world studies. It could be a game-changer for fixing these tough breaks!

Source: Springer