A Game Changer for Knees? Exploring New Bone Cement in Total Knee Replacement

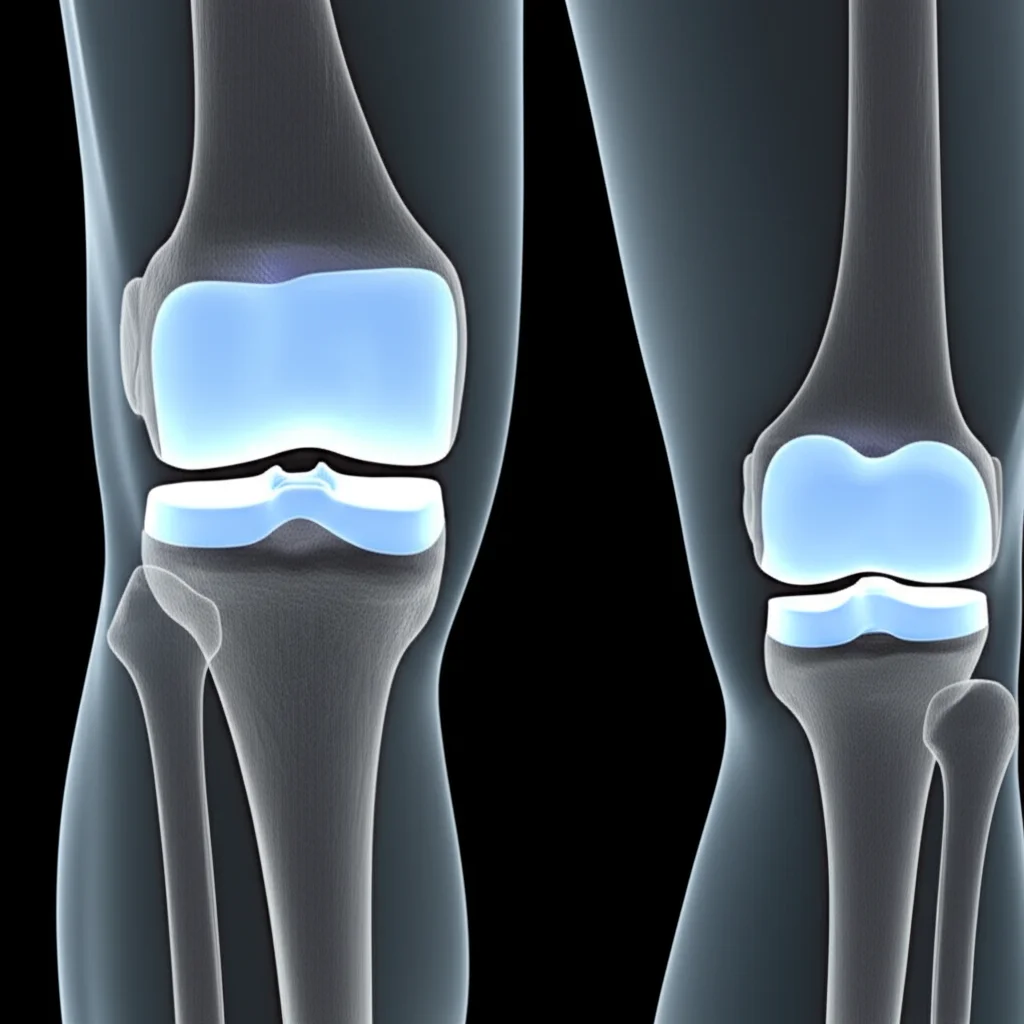

Hey there! So, let’s talk knees. Specifically, those knees that have seen better days, maybe due to stubborn osteoarthritis. When things get really tough, a total knee arthroplasty (TKA), or total knee replacement as most of us call it, is often the go-to solution. It’s pretty amazing how this surgery can bring relief and get folks moving again.

Now, a crucial part of making that new knee stay put is the bone cement. For ages, the standard stuff has been polymethylmethacrylate, or PMMA. It’s been around forever and does a decent job. But, and there’s always a but, it’s not perfect. Think of it like really strong glue – it holds things together, but it doesn’t actually *become one* with your bone. It also has a different stiffness compared to bone, which can sometimes cause issues down the line, like the implant potentially wiggling loose or even tiny fractures forming around it.

Enter the New Material

This is where things get interesting! Scientists and engineers have been working on smarter materials. The idea is to create a bone cement that doesn’t just act like grout but actually encourages your bone to grow onto it, creating a stronger, more natural bond. This study I looked into focuses on a new kind of cement called mineralized collagen-enhanced PMMA, or MC-PMMA for short. What’s in it? Well, it’s the traditional PMMA mixed with something called mineralized collagen (MC). This MC stuff is pretty cool – it’s made in a lab from recombinant human collagen and nano-hydroxyapatite, which are basically building blocks your bone loves. The hope is that adding this MC makes the cement more friendly to bone growth and maybe even gives it better mechanical properties, like being a bit more flexible, closer to the feel of real bone.

Putting the New Cement to the Test

So, how do you figure out if this new MC-PMMA is actually better? You do a study, of course! And this one was set up really smartly. It was a prospective, randomized controlled trial. They found 34 patients who had severe osteoarthritis in *both* knees and needed bilateral TKA (meaning both knees replaced at the same time). Here’s the clever part: in each patient, one knee got the traditional PMMA cement, and the other knee got the new MC-PMMA cement. This is called a self-controlled trial, and it’s great because it means you’re comparing the two cements within the same person, which helps cancel out individual differences.

They followed these patients for an average of about 45.8 months (that’s nearly four years!). During that time, they checked all sorts of things:

- How the patients felt: Using questionnaires like the Knee Society Score (KSS), WOMAC, and HSS scores, which ask about pain, function, stiffness, and daily activities.

- Knee movement: Measuring how much the knee could bend and straighten.

- Pain levels: Using a simple scale.

- Complications: Keeping an eye out for anything going wrong, like infections, the implant coming loose (aseptic loosening), fractures, or needing another surgery (revision).

- X-rays: Looking at the alignment of the leg and checking for any gaps or lines (radiolucent lines, or RLLs) appearing between the cement and the bone, which can be a sign of loosening.

It was a thorough look to see if the new cement performed as safely and effectively as the old one.

What Did They Find? The Results Are In!

Okay, so after all that careful tracking, what did the study reveal? This is where it gets a little nuanced.

The most exciting finding was that the group who received the MC-PMMA cement showed a significantly improved Knee Society function score compared to the traditional PMMA group at the one-year follow-up. This is pretty cool! It suggests that maybe, just maybe, the new cement helps people get back to doing their daily activities a bit better or faster in that crucial first year after surgery.

However, when they looked at the *latest* follow-up (remember, nearly four years out), they didn’t find significant differences between the two groups in most other measures. Things like overall HSS, KSS knee score, WOMAC scores, knee range of motion, and pain levels were pretty similar between the MC-PMMA and T-PMMA knees.

Radiographically, the knees looked similar too. The alignment angles (Hip-Knee-Ankle and anatomical axis) were corrected equally well by both cements, and importantly, there was no significant difference in the appearance of those radiolucent lines (RLLs) that can signal loosening. The RLLs they did see were small and didn’t seem to be getting worse, which is good news for both types of cement in the mid-term.

And complications? Thankfully, they were low and similar for both groups. No infections, no aseptic loosening (where the implant wiggles loose without infection), no fractures around the implant, and nobody needed another surgery during this follow-up period. This is a big relief – it suggests the new cement is at least as safe as the old one.

Interestingly, they even asked patients if they preferred one knee over the other, without telling them which knee got which cement. The results were pretty mixed – some preferred the T-PMMA side, some the MC-PMMA side, and many felt no difference at all. So, no strong preference there from the patients themselves in the mid-term.

Why Might This Be Cool (Even if the Differences Weren’t Huge Yet)?

Even though the big differences weren’t everywhere, that one-year functional improvement is intriguing. And the *idea* behind MC-PMMA is still really promising. Remember how I mentioned the elastic modulus (stiffness)? The source text points out that previous studies showed MC-PMMA has a lower elastic modulus than traditional PMMA, making it closer to the stiffness of cancellous bone. This *could* potentially lead to better stress distribution and reduce the risk of problems over the very long term, though this study didn’t prove that yet.

Plus, the mineralized collagen component is designed to be osteoinductive and osteoconductive – fancy words meaning it encourages bone cells to grow and provides a scaffold for them. Previous lab and animal studies hinted that MC-PMMA could lead to bone actually growing *into* the cement interface. The biodegradability of the MC might even create tiny pores over time, giving bone tissue space to grow into. While this study’s X-rays didn’t definitively show better bone integration compared to T-PMMA, the *potential* is there based on the material’s properties and earlier research.

So, MC-PMMA seems safe, performs comparably to traditional cement in the mid-term, and might offer a kickstart to functional recovery in the first year. It represents a step towards bone cements that are more biologically active and potentially integrate better with the host bone, moving beyond just being a passive filler.

The Caveats and What’s Next

Like any good study, this one has its limitations, and the researchers are upfront about them. First off, 34 patients isn’t a massive group, so the study might not have been big enough to spot smaller but still meaningful differences between the two cements. Secondly, the follow-up period, while decent at nearly four years, isn’t “long-term” in the world of joint replacements, which are ideally meant to last 15-20 years or more. We need to see how these knees hold up over a decade or two.

Also, the way they checked for bone integration was mainly by looking for those radiolucent lines on standard X-rays. While useful, more advanced techniques like radiostereometric analysis (RSA) or biomechanical testing could give a much clearer picture of how well the cement is truly bonding with the bone and how stable the implant is.

But despite these points, the study’s self-controlled design (comparing knees in the same patient) is a real strength, helping to make the results more reliable for what they *did* find.

The takeaway? MC-PMMA looks like a safe and effective option for cemented total knee replacement, performing just as well as the traditional stuff in the mid-term and potentially offering a slight edge in early functional recovery. It’s a promising step forward, hinting at the potential of using smart, nano-engineered materials in orthopedics. But, as is often the case in science, more research is definitely needed – bigger studies, longer follow-ups, and more sophisticated ways to see exactly what’s happening at that crucial bone-cement interface. It’s an exciting area to watch!

Source: Springer