Homebound Ants Are the Best Navigators for Naive Foragers!

Hey there! Ever watch ants scurrying around and wonder how they know where they’re going? It’s pretty amazing, right? We often think of their little pheromone trails as the main highway system, and they totally are! These chemical breadcrumbs are super important for keeping the colony organized, especially when it comes to finding food.

But here’s a thought: what happens when those little highways get busy? Does seeing other ants coming and going make a difference? Especially for the newbies, the ‘naive’ ants who haven’t been to the snack bar before? That’s what a fascinating study recently dug into, and honestly, the results are pretty cool.

Setting Up the Ant Commute

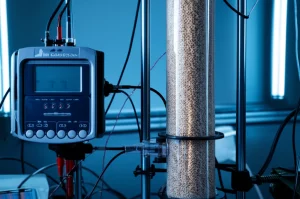

So, these clever folks wanted to see how naive ants from a colony of *Lasius niger* (that’s your common garden ant!) handled getting to a food source under different traffic conditions. They built a little bridge connecting the nest to a feeder, creating a controlled environment. They set up four main scenarios:

- Condition 1 (The Main Event): A pheromone trail was laid down, and naive ants only encountered other ants coming *back* from the feeder (unidirectional inward traffic). Think of it as a one-way street for returning commuters.

- Condition 2 (Pheromone Only): A pheromone trail was present, but there was no ant traffic at all. Just the smell.

- Condition 3 (The Wild West): No pheromone trail, and no ant traffic. The ants were pretty much on their own.

- Condition 4 (Rush Hour): A pheromone trail was there, and naive ants encountered ants going *both* toward the feeder and returning from it (bidirectional traffic). A busy two-way street!

They specifically used naive ants – ones who hadn’t been on this particular route before – to see how these external cues influenced their very first trip.

The Speedy Surprise

And guess what? The ants in Condition 1, the ones who only met buddies coming *back* from the snack bar, reached the feeder significantly faster than the ants in any of the other three conditions!

Let’s break down the average travel times:

- Unidirectional Inward Traffic (Meeting returners): Around 17 seconds

- Pheromone Only: Around 24 seconds

- No Pheromone, No Traffic: Around 27 seconds

- Bidirectional Traffic (Meeting everyone): Around 23 seconds

See that? Meeting *only* the returning crowd shaved off a good chunk of time compared to just following a scent, wandering alone, or navigating a chaotic two-way street.

Why the Speed Boost?

So, why were the naive ants faster when they only met returners? The researchers reckon it might be down to specific cues from those homebound ants. Maybe they carry tiny traces of food on their mandibles that act as an extra attractant? Or perhaps their behavior, their confident stride back to the nest, acts as a kind of *motivational signal* or confirmation that they’re on the right track to success.

Think about it: if you’re lost and you see someone walking confidently towards a destination, you might follow them, right? Even if you also have a map (the pheromone trail), seeing someone who’s *been there* adds an extra layer of confidence and guidance.

Navigating the Ant Highway

The study also looked at *how* the ants moved. They measured ‘angular displacement’ – basically, how much the ants meandered or changed direction. Interestingly, ants in the bidirectional traffic (Condition 4) meandered *more* than those in the unidirectional inward traffic (Condition 1) or the pheromone-only condition (Condition 2). It’s like trying to walk straight in a crowded hallway versus a less busy one – you have to dodge and weave more.

Speed was also measured. Ants in Condition 1 (unidirectional inward traffic) were faster than those in Condition 2 (pheromone only) and Condition 3 (no pheromone/no traffic). However, their speed wasn’t significantly different from the ants in the chaotic bidirectional traffic (Condition 4). This is a bit counter-intuitive, right? They were faster overall (less time to the feeder) but not necessarily *moving* faster than in the bidirectional condition.

This suggests that it’s not just about raw speed, but about *efficiency* of movement. Even if they were moving at a similar pace in both busy conditions, the ants facing only returners (Condition 1) were somehow more direct, less hesitant, or better guided, leading to a shorter overall travel time. The extra meandering in Condition 4 likely ate up precious time, even if they were moving quickly between changes in direction.

More Than Just Bumps

One cool finding was that the *number* of times a naive ant bumped into or got close to another ant didn’t seem to be the key factor in how fast they got there. This tells us it’s not just about physical collisions or density. It’s something more nuanced about the *direction* and *status* (returning vs. outgoing) of the ants they encounter. Ants aren’t just simple particles bouncing off each other; they’re using social cues in a sophisticated way.

Previous research has hinted at this complexity. Ants can adjust how much pheromone they lay down based on who they meet. They might prefer trails with other ants on them. And they can even use the geometry of the trail network itself as a directional cue. This study adds another layer: the *flow* of traffic matters, and meeting successful returners seems to be a particularly powerful signal for naive foragers.

The Takeaway

So, what does this all mean? Foraging efficiency is crucial for a colony’s survival. Getting food back quickly means more energy for everyone. This study highlights that while pheromones are essential, social interactions – specifically encountering ants who have successfully found food and are heading home – provide a vital boost, especially for inexperienced individuals. It’s like getting a friendly nudge in the right direction from someone who knows the way.

This could be particularly important in the early stages of discovering a new food source, when the pheromone trail is still being established. Naive ants quickly finding the feeder by following the first returners could kickstart the recruitment process and benefit the entire colony.

It just goes to show that even in the tiny world of ants, communication and social cues are incredibly complex and fascinating!

Source: Springer