Tiny Heroes: How Multi-Drug Nanomedicine is Supercharging the Cancer Fight

Hey there! So, I recently got my hands on this fascinating deep dive into the world of cancer treatment, specifically looking at something called multi-drug nanomedicine. And let me tell you, it’s pretty mind-blowing stuff. We all know cancer is a tough cookie, right? It’s complex, it’s sneaky, and often, hitting it with just one type of treatment isn’t enough. That’s why doctors often use combinations of therapies, sometimes even mixing different drugs together.

Now, combining drugs sounds simple enough, but in reality, it’s a huge headache. Different drugs behave differently in the body – they get absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and excreted at different rates. This makes it super tricky to get them to the right place, at the right time, and in the right amounts to work together effectively. It’s like trying to conduct an orchestra where every musician is playing a different tempo!

Why Combinations Are Key (and Why They’re Hard)

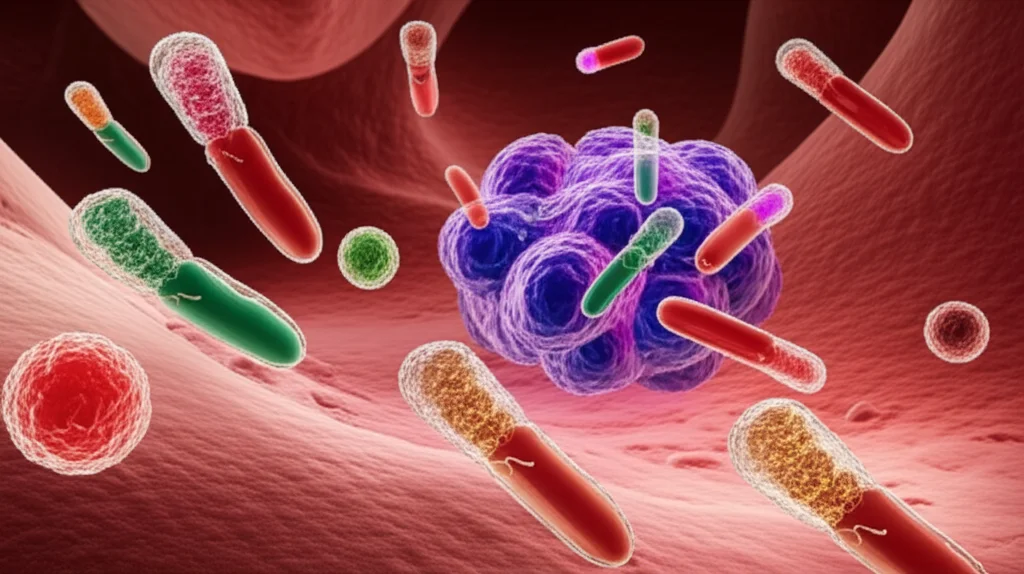

Think about it. Cancer isn’t just one thing; it’s a whole bunch of rogue cells playing by their own rules. To really tackle it, you often need to hit multiple pathways or targets at once. That’s where drug combinations come in. They can be way more effective than single drugs because they can:

- Target different aspects of the cancer cell itself.

- Influence the surrounding environment (the tumour microenvironment).

- Even boost the body’s own immune response against the cancer.

But, as I mentioned, the logistical nightmare of getting free drugs with wildly different properties to cooperate inside the body is a major hurdle. Their uncoordinated journey means you might not get the synergy you hoped for, and you could end up with more side effects because drugs go where they’re not needed.

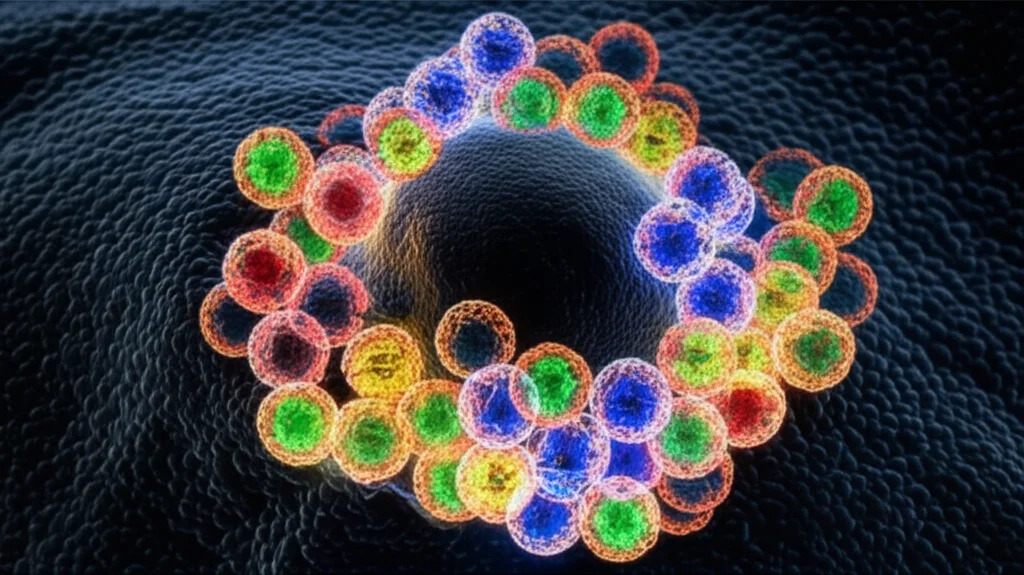

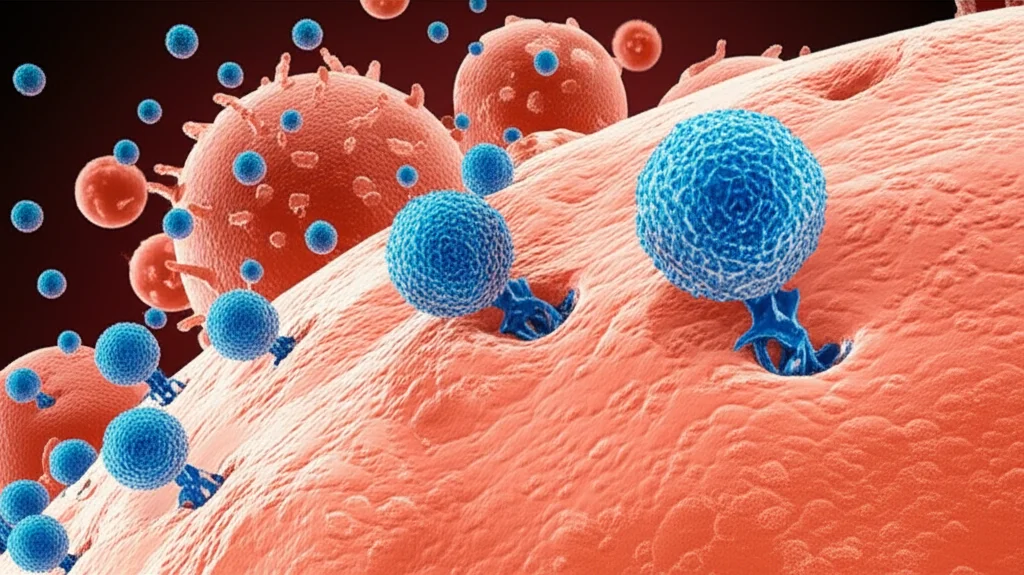

Enter Nanomedicine: The Tiny Delivery Service

This is where nanomedicine swoops in like a superhero, albeit a microscopic one. Nanoparticles are these tiny structures, way smaller than a human cell, that can be engineered to carry drugs. They offer some awesome advantages:

- They can protect drugs, making them more stable.

- They can make drugs that don’t dissolve well in water (which is most of our body!) easier to deliver.

- They can be designed to hang around in the bloodstream longer.

- Crucially, they can be designed to preferentially accumulate in tumours (thanks to leaky blood vessels there, a phenomenon called the EPR effect, or sometimes with added targeting molecules).

- They can control *when* and *where* the drug is released.

So, if single-drug nanomedicine is great, what about multi-drug nanomedicine? The idea is to load *more than one* drug into the *same* nanoparticle. This way, the drugs travel together, arrive at the tumour site together, and ideally, even get inside the same cancer cells together, maintaining a specific, potentially synergistic, ratio.

A fantastic real-world example of this is a drug called Vyxeos. It’s a liposomal (fat-based nanoparticle) formulation that packs two chemotherapy drugs, cytarabine and daunorubicin, together in a fixed 5:1 ratio. This specific combo, delivered together in the nanoparticle, has shown significantly better survival rates for certain types of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) compared to giving the same drugs separately.

The Big Picture: What This Study Found

Now, while Vyxeos is a success, a really comprehensive, quantifiable analysis of multi-drug nanomedicine versus other approaches was kind of missing. That’s what this study set out to do. The researchers dug through a massive amount of pre-clinical data – 273 studies in mice, to be exact – comparing different treatment strategies for cancer:

- Single free drug therapy (just one drug, not in a nano-carrier).

- Free drug combination therapy (two or more drugs given separately, not in nano-carriers).

- Single-drug nanotherapy (one drug loaded into a nano-carrier).

- Multi-drug nanotherapy (two or more drugs loaded into the same or separate nano-carriers, given together).

And the results? Pretty compelling! The analysis showed that multi-drug nanotherapy wasn’t just a little bit better; it significantly outperformed all the other groups in reducing tumour growth. We’re talking:

- 43% better than single free drug therapy.

- 29% better than free drug combination therapy.

- 30% better than single-drug nanotherapy.

That’s a serious improvement! Not only that, but multi-drug nanotherapy also led to the best survival rates. A whopping 56% of studies using this approach showed complete or partial survival of the mice, compared to only 20-37% for the other treatment types. This really solidifies the value of multi-drug nanomedicine as a powerful way to improve how we fight cancer.

Getting Down to Details: How We Deliver

One of the most interesting findings for me was the difference between *how* the drugs were combined in the nanomedicine. The study looked at two main strategies:

- Co-delivery: Both drugs are loaded into the *same* nanoparticle.

- Separate delivery: The two drugs are loaded into *two different* nanoparticles, and these are given together or sequentially.

Guess which one worked better? Yep, co-delivery! Loading the two drugs into the same nanoformulation reduced tumour growth by a further 19% compared to giving them in separate nanoparticles. This makes a lot of sense. If you need the drugs to work together synergistically *inside* the same cell, putting them in the same delivery vehicle dramatically increases the chances they’ll arrive there together, in the right ratio. It’s like sending a dynamic duo on a mission in the same car versus hoping they both catch separate buses and arrive at the hideout at the same time!

Nanocarrier Nitty-Gritty

The study also peeked into the specifics of the nanoparticles themselves. They looked at things like the material they were made of, whether they had special targeting molecules, and if they were coated with PEG (polyethylene glycol), which is often used to help nanoparticles avoid being cleared too quickly by the body.

When comparing different nanocarrier materials (lipids, polymers, inorganic materials, etc.), they found that *all* of them improved outcomes compared to free drugs. However, there wasn’t a significant difference in efficacy *between* the different materials when it came to multi-drug combination nanotherapy. It seems the benefit comes more from the fact that they’re *in* a nanocarrier, rather than the specific type of material, at least based on this analysis.

What about targeting? Nanoparticles can rely on passive targeting (accumulating in tumours due to leaky blood vessels) or active targeting (having molecules on their surface that bind to specific receptors on cancer cells). The analysis showed a trend towards active targeting being better, especially for multi-drug nanotherapy. This could be because active targeting helps get the nanoparticles (and thus, both drugs together) *into* the cancer cells, where that synergistic ratio is most needed.

Interestingly, adding a PEG coating didn’t show a significant boost in outcome for multi-drug nanomedicine in this study. PEGylation is a bit of a double-edged sword – it helps nanoparticles circulate longer, but it can also sometimes reduce their uptake by target cells and even cause immune reactions. For certain applications, like treating blood cancers where the cells are easily accessible, non-PEGylated formulations like Vyxeos might be just fine, or even better.

Across the Board: Cancer Types and Resistance

One of the most reassuring findings was that the benefits of multi-drug nanotherapy weren’t limited to just one or two types of cancer. The study looked at data across various tumour models (breast, lung, colon, etc.), and in *every single one*, multi-drug nanotherapy showed the biggest reduction in tumour growth. This suggests it’s a broadly applicable strategy.

Even more exciting, this approach showed significant benefits even in tumours that were resistant to chemotherapy! While resistant tumours didn’t respond well to single free drugs, free drug combinations, or even single-drug nanotherapy, multi-drug nanotherapy was able to significantly reduce their growth. This is huge, as drug resistance is a major reason why cancer treatments fail.

The analysis also confirmed the benefits in both xenograft models (human tumours grown in mice with suppressed immune systems) and allograft models (mouse tumours grown in mice with normal immune systems). This suggests the benefits aren’t solely dependent on the immune system’s interaction with the nanomedicine, although that’s a complex area still being explored.

Looking Ahead: Challenges and Opportunities

So, multi-drug nanomedicine looks incredibly promising based on this pre-clinical data. But translating these findings from mice to humans is the next big hurdle. Mice and humans are different, and nanoparticles can behave differently in our bodies, especially in how long they circulate. We need more studies, maybe even in non-human primates, to get a better idea of how these will work in people.

There’s also the issue of publication bias – researchers are more likely to publish positive results than negative ones. While the study tried to account for this, it’s a factor to keep in mind. However, the overwhelming trend in the data is strongly in favor of multi-drug nanotherapy.

It’s also important to be smart about *when* and *why* we use multi-drug nanomedicine. As the study points out, co-loading drugs in the same nanoparticle is probably most critical when you need those drugs to work together *inside* the same target cell, like with Vyxeos for leukaemia cells. If you’re combining a chemotherapy drug with something that targets the tumour microenvironment or activates immune cells (which might be located elsewhere), co-encapsulating them might not be strictly necessary from a purely pharmacological standpoint, though it could still make sense for manufacturing or regulatory reasons.

Despite the challenges, the potential is massive, not just for cancer, but for other diseases too. Imagine nanoparticles delivering multiple drugs for HIV, tuberculosis, or even gene therapy components precisely where they’re needed! The field is still young, but with strong evidence like this, I expect we’ll see a lot more multi-drug nanomedicines making their way from the lab towards the clinic in the coming years. It’s an exciting time in the fight against complex diseases.

Source: Springer