Unmasking the Engine Driving Thyroid Cancer: A METTL1 Story

Hey there, fellow science enthusiasts! You know, sometimes in the world of cancer research, we feel like detectives piecing together a really complex puzzle. We’re always looking for those hidden culprits, those molecular switches that flip a normal cell into a rogue one, driving it to grow and spread. And let me tell you, we’ve just uncovered a fascinating piece of that puzzle in papillary thyroid cancer (PTC).

PTC is the most common type of thyroid cancer, and while many patients do really well, it still has this tricky tendency to invade surrounding tissues and spread to lymph nodes. We know some common genetic mutations kick things off, but honestly, they don’t explain *all* cases. So, we’re on the hunt for other mechanisms, the ones that might be working behind the scenes, independent of those usual suspects.

What’s the Big Deal with PTC?

Okay, so PTC is prevalent, making up over 80% of thyroid cancers. It’s known for being a bit sneaky, often infiltrating nearby structures and heading for the lymph nodes. While the long-term survival rate is pretty good (over 90% at 10 years, which is fantastic!), dealing with lymph node involvement, invasion, and sometimes even distant spread is a major challenge. We really need to understand the molecular networks at play to find new ways to stop it in its tracks.

The RNA World and Cancer

For a long time, DNA got all the glory. It holds the blueprint, right? But increasingly, we’re realizing that RNA, the molecule that carries instructions from DNA to build proteins, is just as crucial, and it’s got its own secret life! This field, called epitranscriptomics, studies modifications on RNA molecules. Think of them like little sticky notes or highlights on the instructions, changing how they’re read or used.

There are over 160 different chemical modifications found in various RNAs! One you might have heard of is m6A on messenger RNA (mRNA), which has been linked to several cancers like leukemia, lung, and liver cancer. It’s shown us that cancer progression isn’t just about changes in the DNA sequence; it’s also heavily influenced at the post-transcriptional level.

But guess what? Transfer RNAs, or tRNAs, are even *more* heavily modified than mRNAs. These little guys are the translators – they read the mRNA code and bring the right amino acids to build proteins. Their modifications are super important for making sure translation happens accurately and efficiently. And when these tRNA modifications go wrong, they’ve been linked to all sorts of health issues, including different types of cancer.

Enter METTL1 and m7G

One specific modification we’re talking about is N7-methylguanosine (m7G), often found at position 46 on tRNAs. And the main enzyme complex responsible for putting this m7G mark on tRNAs is called METTL1/WDR4. METTL1 does the actual methyl-adding work, while WDR4 helps stabilize the whole operation.

This m7G modification has been known about for a while, even in simple organisms like yeast. But more recently, studies have shown that METTL1/WDR4-mediated m7G tRNA modification is strongly tied to tumor development and progression in mammals. However, its specific role in *papillary thyroid cancer*? That was still a bit of a mystery.

Our Deep Dive: METTL1 in PTC

So, we decided to take a really close look. We wanted to see if METTL1 was involved in PTC and, if so, how it might be driving those aggressive behaviors like proliferation and metastasis. And boy, did we find something interesting!

METTL1: A Bad Sign for Prognosis

First off, we checked out public databases containing data from lots of PTC patients. What we found was pretty clear: METTL1 levels were significantly higher in PTC tissues compared to normal thyroid tissue. And not just METTL1, but its partner-in-crime, WDR4, was also upregulated. This wasn’t just some random observation; higher levels of both METTL1 and WDR4 were strongly associated with shorter overall survival for PTC patients. Think of them as potential warning signs.

To make sure this wasn’t just a fluke in public data, we looked at actual PTC tissue samples from patients. We saw the same pattern: METTL1 was much more frequently upregulated in tumor tissue than in adjacent normal tissue. And when we looked at clinical features, both METTL1 and WDR4 levels were positively correlated with lymph node metastasis – that’s a big deal because lymph node spread is a key factor affecting prognosis. In fact, our analysis suggested that METTL1 expression could be an independent predictor of how a patient might fare, similar in importance to the standard AJCC stage.

These initial findings strongly suggested that METTL1 and WDR4 aren’t just hanging out in PTC; they might be actively involved in making the cancer more aggressive.

METTL1 Fuels Cancer Growth and Spread

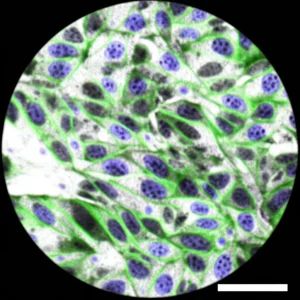

Okay, so METTL1 is upregulated and linked to bad outcomes. But is it actually *causing* the cancer to grow and spread? To figure this out, we did some experiments in the lab using PTC cell lines. We used techniques to ‘knock down’ or reduce the amount of METTL1 in these cells.

The results were striking! When we reduced METTL1, the PTC cells didn’t proliferate as much, and their ability to form colonies (a measure of their growth potential) was significantly reduced. We also looked at the cell cycle, which is like the cell’s life clock. METTL1 knockdown seemed to cause an arrest in the S-phase, effectively putting the brakes on cell division.

Beyond just growing, cancer cells need to move and invade to spread. So, we tested the migration and invasion capabilities of the cells. Again, reducing METTL1 markedly inhibited how well the PTC cells could migrate and push through barriers. It was clear that METTL1 was playing a role in these aggressive behaviors *in vitro* (in the lab dish).

But what about *in vivo* (in living organisms)? We took these cells and injected them into mice to create a xenograft model. The mice injected with cells where METTL1 was knocked down developed significantly smaller tumors that grew much slower than the control group. We even saw reduced cell proliferation within the tumors (measured by Ki-67 staining). To specifically look at metastasis, we injected cells into the footpads of mice, a model that mimics lymph node spread. And yes, you guessed it – reducing METTL1 significantly decreased the volume of metastatic lymph nodes. These animal studies really confirmed that METTL1 is crucial for driving PTC growth and metastasis in a living system.

![]()

It’s All About the Methyltransferase Activity

Now, METTL1 is a methyltransferase enzyme. This means its main job is to add methyl groups to other molecules, specifically tRNAs in this case. We wondered if this enzymatic activity was essential for its cancer-promoting effects. We created a version of METTL1 with a specific mutation that disables its methyltransferase activity (like breaking the tool it uses to do its job).

When we put this catalytically inactive mutant METTL1 into PTC cells, it *didn’t* promote proliferation, migration, or invasion like the normal, active METTL1 did. The same was true in the mouse models – the mutant METTL1 couldn’t drive tumor growth. This told us loud and clear that METTL1’s ability to add those m7G marks to tRNAs is absolutely necessary for it to fuel PTC progression.

Finding the Downstream Culprit: TNF-α

Okay, so METTL1’s enzymatic activity on tRNAs is important. But how does that *lead* to increased cancer growth and spread? What are the specific downstream targets that METTL1 is influencing? To find this out, we did a deep dive using multiple ‘omics’ approaches – looking at both the RNA levels (transcriptome) and protein levels (proteome) in cells with and without METTL1 knockdown.

We found a bunch of genes and proteins that were affected. When we analyzed these changes, one pathway kept popping up as significantly downregulated when METTL1 was reduced: the TNF-α-mediated signaling pathway. Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) is a molecule known to play complex roles in cancer, sometimes inhibiting it, but often promoting growth and spread in many types, including PTC, where it’s been linked to activating metastatic abilities.

We confirmed that many genes downstream of TNF-α signaling were indeed inhibited in cells with reduced METTL1. We also saw that the PI3K/AKT pathway, a major signaling route often activated by TNF-α and involved in cell growth and survival, was less active when METTL1 was knocked down. Furthermore, we saw that TNF-α itself was highly expressed in PTC tumor tissues compared to normal tissues, just like METTL1 and WDR4.

This made TNF-α look like a very strong candidate for being a key target of METTL1 in PTC.

The Post-Transcriptional Twist: Translation

Now, here’s where it gets really interesting. We looked directly at TNF-α expression in cells with and without METTL1. We found that reducing METTL1 didn’t change the *amount of TNF-α mRNA*. The instructions were still there. But, the *amount of TNF-α protein* and the amount of TNF-α secreted by the cells dropped significantly! This is a classic sign that METTL1 isn’t affecting the gene’s transcription (making the mRNA) but rather its *translation* (making the protein from the mRNA), or maybe protein degradation.

We checked protein degradation, and nope, METTL1 didn’t seem to affect how fast TNF-α protein was broken down. This left translation as the prime suspect.

Unpacking the Translation Story

Since METTL1 modifies tRNAs, and tRNAs are essential for translation, this all started to make sense. Could METTL1 be boosting the translation of specific proteins, like TNF-α, by modifying certain tRNAs?

First, we did a general test of translation efficiency using a method called a puromycin intake assay. Puromycin gets incorporated into newly synthesized proteins. We saw that when METTL1 was knocked down, the overall amount of puromycin incorporated decreased, meaning global protein translation was less efficient. This supported the idea that METTL1 influences translation.

Next, we used a fancy technique called TRAC-seq to specifically look at the m7G modifications on tRNAs. We found 23 specific tRNAs whose m7G modification levels were significantly reduced when METTL1 was knocked down. This confirmed that METTL1 is indeed responsible for modifying these particular tRNAs.

Then, we did some clever analysis. We looked at the ‘codons’ (three-letter genetic words) that these 23 tRNAs are designed to translate. We found that these codons were more frequently present in the mRNA sequence of TNF-α than in other control mRNAs like β-actin. This suggested that METTL1-modified tRNAs might be particularly important for translating TNF-α mRNA.

To really nail this down, we did a cool experiment. We created modified versions of the TNF-α mRNA sequence. In these mutant versions, we swapped out the codons that are translated by the METTL1-modified tRNAs for ‘synonymous’ codons – different three-letter words that code for the *same* amino acid but are translated by *different* tRNAs (presumably ones not modified by METTL1). We put these wild-type and mutant TNF-α mRNAs into cells with and without METTL1 knockdown.

The result? Wild-type TNF-α mRNA was translated much less efficiently in cells lacking METTL1. But the mutant TNF-α mRNA, with the swapped codons, was translated at almost normal levels, even when METTL1 was reduced! This was a huge piece of evidence showing that METTL1 regulates TNF-α translation specifically through its m7G tRNA modification activity, likely by ensuring the availability of the right tRNAs to read specific codons in the TNF-α mRNA.

We also showed that overexpressing normal, active METTL1 increased TNF-α protein levels and secretion, while the catalytically dead mutant METTL1 did not. This further cemented the link between METTL1’s enzymatic activity, tRNA modification, and TNF-α translation.

TNF-α: The Key Player Downstream

So, we had strong evidence that METTL1 boosts TNF-α translation via m7G tRNA modification. But was TNF-α actually *required* for METTL1 to drive cancer progression? To test this, we performed ‘rescue’ experiments. We took cells where METTL1 was knocked down (and thus had reduced proliferation/metastasis) and added back recombinant TNF-α protein.

Adding exogenous TNF-α partially restored the ability of these cells to proliferate and metastasize, both in the lab and in the mouse models. This confirmed that TNF-α is a crucial downstream target mediating METTL1’s effects. As a final check, we used a specific inhibitor of TNF-α signaling, R-7050. As expected, this inhibitor significantly blocked the proliferation and metastasis of wild-type PTC cells. It really highlighted TNF-α’s role in this whole process.

Clinical Connections

Bringing it back to the clinic, we looked at patient tissue samples again. We found that PTC tissues from patients with lymph node metastasis had higher levels of METTL1, WDR4, and TNF-α compared to those without metastasis. And confirming the molecular link, the protein levels of METTL1, WDR4, and TNF-α were all positively correlated with each other in these patient samples. This clinical data strongly supports our lab findings – METTL1, its cofactor WDR4, and TNF-α are working together and are associated with more aggressive disease in patients.

Looking Ahead: Targeting METTL1?

What does this all mean? Well, we’ve uncovered a novel mechanism where the METTL1/WDR4 complex uses m7G tRNA modification to specifically boost the translation of TNF-α, and this drives the proliferation and metastasis of papillary thyroid cancer cells. It’s a beautiful example of how these subtle RNA modifications can have a huge impact on protein levels and, ultimately, cancer behavior.

Understanding this codon-specific translation mechanism is really important. Cancer cells often selectively increase the translation of proteins that help them grow and spread, even if the mRNA levels aren’t dramatically different. Targeting this selective translation could be a powerful new strategy.

While there’s growing interest in targeting RNA modifications for cancer therapy (like inhibitors for m6A modifiers), inhibitors specifically targeting m7G modifications like METTL1 aren’t quite ready for prime time yet. So, targeting METTL1 directly as a therapy is still a bit down the road, which is a limitation of our study in terms of immediate clinical application. But our work provides a strong molecular basis for *why* targeting METTL1 could be a promising approach in the future.

We also got hints that the PI3K/AKT pathway might be involved downstream of TNF-α in this METTL1-driven process. That’s another area ripe for further investigation.

In conclusion, we’ve shown that METTL1 and WDR4, through m7G tRNA modification, are key players in regulating TNF-α translation and driving PTC progression and metastasis. This work sheds light on a previously unclear mechanism in thyroid cancer and points towards METTL1 as a highly promising potential therapeutic target to overcome this disease’s aggressive tendencies.

Source: Springer