Cracking the Code: Predicting Meningioma Grade with MRI, AI, and a Handy Nomogram

Hey There, Let’s Talk Brain Stuff!

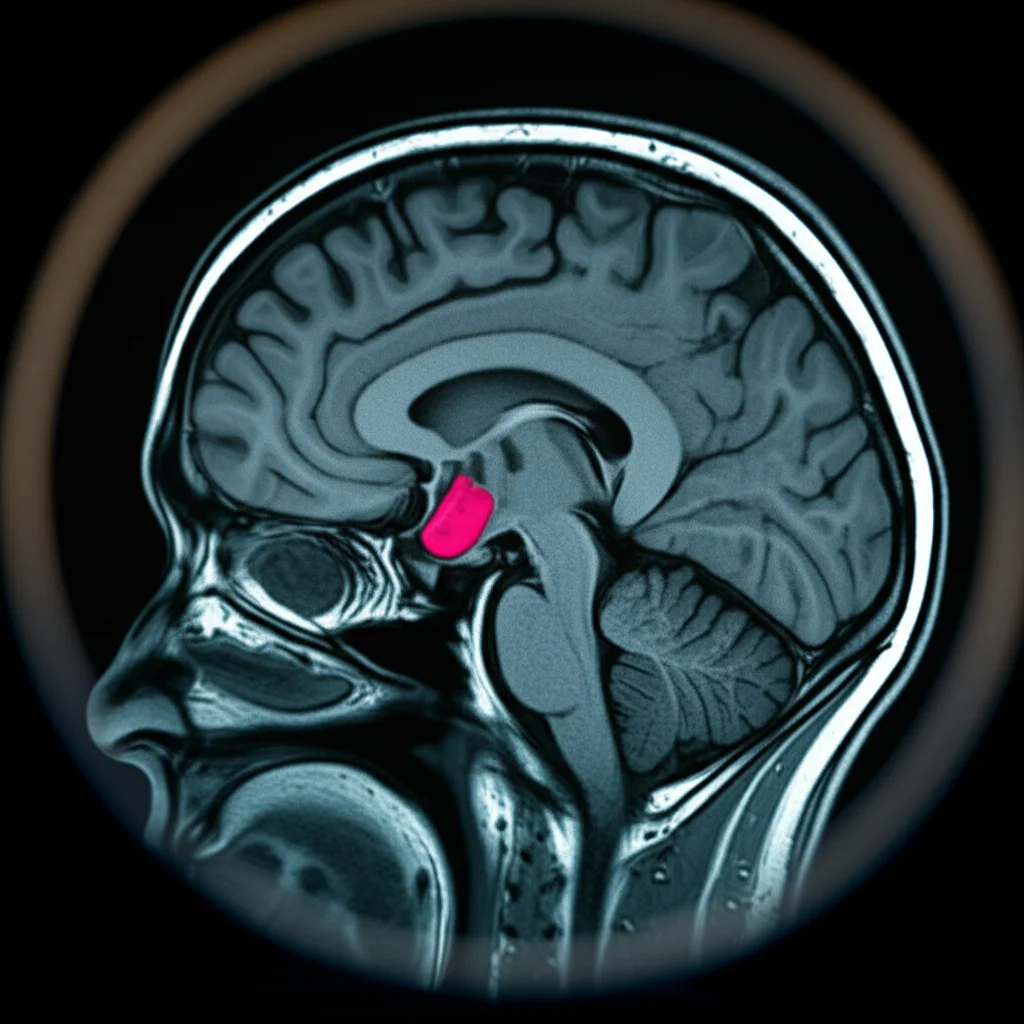

So, you know how sometimes predicting the behavior of something complex is super important? Like, predicting the weather or whether your sourdough starter will actually rise this time? Well, in the world of medicine, predicting how a tumor might behave is *absolutely critical*. And today, I want to chat about a recent study that’s trying to get really good at predicting the grade of a common brain tumor called a meningioma.

Meningiomas are actually the most frequent tumors found inside the skull in adults. We’re talking about over a third of all intracranial tumors! Now, these aren’t all the same. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies them into three grades: 1, 2, and 3. Think of Grade 1 as the chill ones, while Grades 2 and 3 are the more aggressive types. These higher-grade tumors are more likely to come back and have a less favorable outlook. And because of that, how doctors treat them is totally different.

Why Predicting Grade is a Big Deal

Knowing the grade *before* surgery or other treatments is a massive advantage. For high-grade tumors, getting as much of it out as possible during surgery is key, and sometimes other therapies like chemo or targeted drugs are considered if surgery can’t get it all. Low-grade ones might just need surgery and then keeping an eye on things, maybe some radiation down the line. See? Different grades, different game plans. Getting it right upfront means better planning and hopefully, better results for patients.

Traditionally, figuring out the grade involves looking at scans and maybe taking a biopsy. But what if we could get a really strong prediction just from the imaging data we already have, like an MRI?

Enter Radiomics and Deep Learning

This is where some cool tech comes in. You might have heard of AI in medicine, and that’s exactly what we’re talking about here. Two big players are:

- Radiomics: This is like being a super-sleuth with medical images. It extracts tons of quantitative features from scans – things you might not even notice with the naked eye, like textures, shapes, and intensity variations. It turns the image into mineable data.

- Deep Learning (DL): This is the fancy AI stuff, often using neural networks like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). They can learn to recognize complex patterns directly from images. The challenge in medical research is often the limited number of images compared to, say, training a model to recognize cats and dogs on the internet.

That’s where Deep Transfer Learning (DTL) shines in the medical world. Instead of building a model from scratch with limited medical images, you take a model already trained on a *huge* dataset (like ImageNet, which has millions of everyday pictures) and then “fine-tune” it on your smaller medical dataset. It’s like teaching a seasoned artist a new style – they already have the fundamental skills, they just need to adapt them.

Lots of smart folks have used radiomics or DTL separately to try and predict meningioma grade. But, as far as the authors of this study knew, no one had put *all* the pieces together – clinical info, radiomics, *and* DTL – into one easy-to-use tool. And that’s exactly what they set out to do: build a nomogram combining all these factors.

What’s a Nomogram and Why Use One?

Okay, a nomogram sounds complicated, but it’s actually designed to make things *simpler*. Imagine a chart where you find your patient’s characteristics (like sex, or a score from their scan data), you add up points based on these characteristics, and that total score points to a predicted risk – in this case, the risk of having a high-grade meningioma. They’re fantastic because they’re:

- Visual: Easy to see how different factors contribute to the risk.

- Intuitive: You can quickly estimate a patient’s risk without needing complex software right there.

- Practical: Great for communicating risk to other doctors or even patients.

So, the goal was to create this combined clinical, radiomics, and DTL (DTLR) nomogram to predict meningioma grade using standard enhanced T1-weighted MRI images. This is the kind of scan doctors get routinely.

How They Did It (The Nitty-Gritty, Briefly)

The researchers gathered MRI data from hundreds of patients across two hospitals. They focused on enhanced T1WI scans because the tumor boundaries are usually clearest there (and frankly, because that’s the scan most patients had available!). They carefully processed the images, standardizing things like size and intensity.

Then came the feature extraction:

- Clinical Features: They looked at things like the patient’s sex, the tumor’s shape, whether its edges were clear or indistinct, and if there was swelling around it (peritumoral edema).

- Radiomics Features: They extracted over a thousand detailed texture and shape features from the tumor area on the MRI.

- DTL Features: They used that fine-tuning trick with a pre-trained model called ResNet50 on the tumor images to extract deep learning features.

After extracting all these features, they used statistical methods to pick the *most important* ones for predicting grade and built different models: one just with clinical features, one with radiomics features, one with DTL features, and finally, the big one – the DTLR nomogram combining selected clinical features, a summary score from the radiomics features (Rad score), and a summary score from the DTL features (DTL score).

Okay, So What Were the Results?

This is where it gets interesting. They tested their models on a separate set of patients (the test set) to see how well they’d work on new data. Here’s the lowdown:

- The clinical model (just using things like sex, shape, margin, edema) was okay, with an AUC (a measure of how well it discriminates between high and low grade) of 0.788.

- The DTLR nomogram, the one combining everything, had the highest AUC in the test set: 0.866. It also showed the best “net benefit” in something called a Decision Curve Analysis (DCA), which basically tells you how useful the model is in a real clinical setting compared to just treating everyone or no one.

This suggests the combined approach is indeed better at predicting grade than just using clinical factors alone.

Now, here’s a little twist. When they did a specific statistical test (the DeLong test) to compare the AUCs of the models, it showed a significant difference between the DTLR nomogram and the *clinical* model, which is great. But it didn’t show a *significant* difference between the DTLR nomogram and the *radiomics* model alone. This got the researchers thinking: maybe the radiomics model by itself is pretty darn good, and adding DTL features, while it *did* improve the AUC in the test set, might not offer a statistically *significant* advantage over radiomics alone, especially considering the extra computational effort DTL requires. They acknowledge this point – it’s a new attempt, and there’s room for improvement and further study here.

What Does This Mean for the Real World?

The potential here is pretty exciting. Imagine a doctor looking at an MRI scan of a suspected meningioma. They can plug some basic patient info and the scores derived from the radiomics and DTL analysis into this nomogram. Instantly, they get a predicted risk percentage for a high-grade tumor. This visual, quantifiable risk assessment can be a powerful tool for deciding the best course of action – maybe pushing for more aggressive surgery if the risk is high, or opting for a less invasive approach and closer monitoring if it’s low.

For example, the nomogram they built gives points for different factors. A male patient with an irregularly shaped tumor, fuzzy edges, and swelling, plus high radiomics and DTL scores, would rack up a high total score, indicating a higher predicted risk of a high-grade tumor. The DCA analysis helps doctors decide *at what risk level* using the model is most beneficial. They suggest using it when the predicted risk is between 20% and 80%.

But, Hold Your Horses… Limitations!

Like any good study, this one has its limits. The researchers are upfront about them:

- It was a retrospective study, meaning they looked back at existing data. This can sometimes introduce biases.

- They didn’t do skull stripping, which is a preprocessing step to remove the skull from the image. The skull is bright on MRI and could potentially mess with the feature extraction. They plan to look into this.

- They only used enhanced T1WI images. While practical because it’s common, using other types of MRI sequences (multiparametric MRI) might provide even more information and improve accuracy.

- They didn’t integrate everything into one big neural network or use newer self-supervised learning methods. Future work could explore this.

- Most importantly, they need a larger sample size from multiple hospitals. This helps ensure the model works well on data from different places and avoids being too specific to the hospitals where it was developed (overfitting).

Wrapping It Up

So, what’s the takeaway? This study represents a really cool, first-of-its-kind attempt to combine clinical information, radiomics, and deep transfer learning into a visual, practical tool – a nomogram – for predicting meningioma grade before surgery. The DTLR nomogram showed promising results, outperforming models based on clinical features alone and showing the best clinical utility in their tests. While the statistical comparison between DTLR and radiomics alone was a bit nuanced, the DTLR approach *did* improve the AUC in the test set, making it a valuable new direction.

It’s not ready for prime time in every clinic just yet – more validation is definitely needed. But it’s a significant step towards using advanced AI techniques on standard MRI scans to give doctors better tools for predicting tumor behavior and planning the best treatment for patients. Pretty neat, right?

Source: Springer