Untangling the Web: My Approach to Vascular Encasement in Parasellar Meningiomas

Hey everyone, let’s chat about something that really keeps us neurosurgeons on our toes: parasellar meningiomas. These aren’t your everyday brain tumors, especially when they decide to get a little too friendly with the brain’s critical plumbing – I’m talking about the internal carotid artery (ICA) and all its important branches. When a tumor wraps itself around these vessels, we call it “vascular encasement.” Imagine trying to delicately remove a stubborn vine that’s tightly wound around a fragile, irreplaceable pipe. One wrong move, and you could be looking at serious consequences, like an ischemic event or stroke. It’s a scenario where the stakes are incredibly high.

But here’s the good news: it’s not an impossible situation. Over the years, I’ve developed a stepwise surgical technique that allows us, in select cases, to aim for a complete resection even when those preoperative scans show the ICA seemingly swallowed by the tumor. The core of my philosophy? We should systematically attempt to resect tumors encasing major vascular structures, all while constantly weighing that delicate balance between the risk of vascular injury and achieving the most extensive resection possible for the patient’s benefit.

The Challenge: A Crowded and Critical Neighborhood

The parasellar region is, to put it mildly, a bit of a tight squeeze. It’s a complex anatomical area where numerous vital vascular and nervous structures are packed into a very confined space. Because everything is so close together, lesions like clinoidal and cavernous sinus meningiomas can easily displace or, worse, encase these structures. This makes surgery a significant challenge, carrying a high risk of vascular injury. We know that vascular encasement is a proven risk factor for ischemic complications when dealing with sphenoid wing meningiomas. Some studies have even pointed to predictive factors for when we might not find those helpful arachnoid planes (the natural, separable layers between brain/vessels and tumor), such as seeing vascular narrowing or peritumoral T2 brain edema on MRI scans.

In a simplified way, think of the parasellar region as a crucial anatomical crossroads. Key players here include the anterior clinoid process (a bony landmark), the optic nerve (your vision’s main cable), and the internal carotid artery (ICA). The anterior clinoid process connects to the sphenoid bone and forms part of the optic canal’s roof. The optic canal itself houses the ophthalmic artery and the optic nerve, which travels medially to the ICA before joining its counterpart from the other side to form the optic chiasm. Then there’s the superior orbital fissure (SOF), a passageway for oculomotor nerves and branches of the trigeminal nerve.

The supraclinoid portion of the ICA is our main concern here. It courses along the medial side of the anterior clinoid process, ducks under the optic nerve, and then heads to the lateral side of the optic chiasm. It eventually bifurcates into the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and middle cerebral artery (MCA). Along its journey, it gives off several important branches:

- The ophthalmic artery, running under and anterolaterally to the optic nerve into the optic canal.

- The superior hypophyseal arteries, heading medially below the chiasm.

- The posterior communicating artery (PComA), a key part of the Circle of Willis, running near the oculomotor nerve to join the posterior cerebral artery (PCA).

- The anterior choroidal artery (AChA), coursing along the optic tract.

When a meningioma encases these delicate structures, it’s like it’s holding them hostage, and our job is to perform a rescue mission.

Setting the Stage: Patient Positioning and Choosing the Right Approach

Alright, so how do I begin? First things first, patient positioning is key. I have the patient positioned supine, with their head fixed in a Mayfield clamp. I like about 10–20 degrees of rotation towards the contralateral (opposite) side of the lesion and the head tilted a bit towards the side we’re working on. A little bit of head extension is also great because it helps facilitate a retractorless surgery, meaning we can often work without needing metal retractors to hold the brain back. One thing I’m careful about is not to rotate the head too much. Over-rotation can mess with your mental anatomical map, which is crucial in these complex cases.

For the surgical approach, an extended pterional approach combined with a postero-lateral orbitotomy usually gives me good access to most parasellar lesions. If the tumor has significant superior development, I might opt for an orbito-pterional or a frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic approach. The postero-lateral orbitotomy involves extensive drilling of the orbital roof and sphenoid ridge. This maneuver exposes the SOF, allows us to section the orbito-temporal meningeal band, and lets us peel the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. These last two steps are paramount to avoid inadvertently entering the cavernous sinus, which could lead to nasty neurovascular injuries.

Getting In: Extradural Steps and Early Decompression

Before I even open the dura (the tough outer membrane covering the brain), I focus on the extradural anterior clinoidectomy and opening of the optic canal. This is a fantastic early move. Why? It can help devascularize the tumor right at the start, decompress the optic nerve if it’s being squashed, and, importantly, helps in locating the supraclinoid ICA. Of course, I’ve already meticulously reviewed the pre-operative images to check for things like clinoid pneumatization (air cells within the bone) or the presence of a carotid foramen, which can alter the anatomy slightly.

Once the dura is opened, the next critical step is to widely open the sylvian fissure (a natural groove on the brain’s surface) and the basal arachnoid cisterns (fluid-filled spaces at the base of the brain). This maneuver is so important because it allows for early identification of the MCA and, as I mentioned, facilitates that retractorless surgery through dynamic retraction – gently working within the brain’s natural planes.

Finding Our Way: Identifying the Optic Nerve and ICA

Now, we start the process of sub-frontal tumor debulking. I usually begin in the frontal sector of the tumor, as this is generally the less dangerous area to start the dissection. As we carefully remove tumor tissue, the goal is to open the falciform ligament and the optic nerve sheath. Sometimes, this sheath itself can be infiltrated by the tumor. Successfully doing this allows for the clear identification of the optic nerve. And once you have a good handle on the optic nerve, the ICA is typically found nearby, at the distal dural ring.

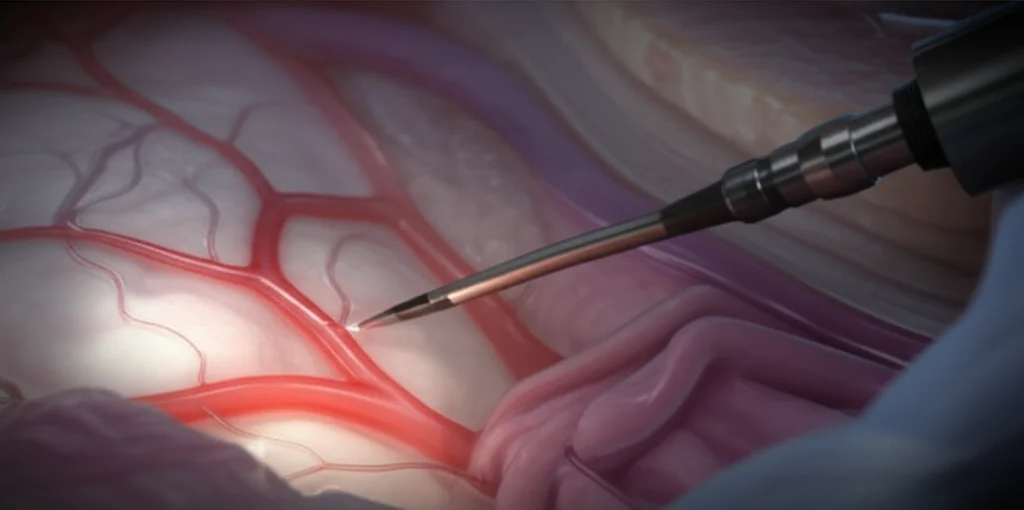

The Main Event: Dissecting the Encased Arteries

This is where the surgery truly becomes a delicate dance. The primary objective here is to identify the encased arteries at their points of entry into and exit from the tumor mass. It’s like tracing wires through a complex bundle. Interestingly, I’ve found that sometimes starting in a retrograde manner – from distal to proximal – can be easier. The origins of the PComA and the AChA are notorious for being areas of very strong adhesion between the tumor and the vessel, so I approach these spots with an extra dose of caution and respect. You have to be patient and meticulous, teasing the tumor away bit by bit.

Navigating with Care: Bleeding Tolerance, Tumor Sectoring, and Tech Aids

A little bit of bleeding, especially in the area posterior to the ICA and towards the oculomotor triangle, should sometimes be tolerated until you’ve clearly identified the AChA, the PComA, and the third cranial nerve (which controls several eye movements). My rule is: avoid coagulation until all vascular and nervous elements are clearly identified. Premature zapping can lead to disaster if you haven’t seen exactly what’s what.

To keep things organized in my head and in the surgical field, I mentally create tumor sectors. These act as landmarks, helping me proceed from known anatomical areas to unknown ones, and from safer zones to more dangerous territories. As the dissection advances, we sequentially create “safe triangles” – these are areas where more and more anatomical elements have been clearly identified and secured.

What about technology? Neuronavigation (think of it as a GPS for surgery) should be used cautiously. I always balance its guidance against direct anatomical landmarks because even a small shift or brain distortion during surgery can make the navigation inaccurate, with potentially catastrophic consequences. In my experience, Doppler probes, which use sound waves to detect blood flow, can often be more reliable for locating encased vascular elements when you’re in a tricky spot.

Important Clues from Pre-op Scans (And Their Limitations)

Before stepping into the OR, I spend a significant amount of time meticulously analyzing the preoperative MRI scans. It’s crucial to have a clear three-dimensional mental representation of the lesion and its intricate relationship with all the main neurovascular structures. While there are no absolutely reliable predictors for whether we’ll be able to cleanly release encased arteries, some imaging features can give us clues. For instance, things like vascular narrowing seen on the scans, or the presence of peritumoral T2 brain edema, have been described as possible indicators that we might not find those nice, clean arachnoid planes we love for dissection.

However, in my experience, one interesting observation is that if the meningioma shows a hyper T2 signal (meaning it appears brighter on T2-weighted MRI sequences), this often seems to correlate with a softer tumor consistency. Softer tumors, generally, are more favorable for dissection around encased vessels. It’s not a foolproof sign, but it’s something I look for as it might suggest a better chance of freeing those arteries.

Words of Wisdom: My Guiding Principles in These Cases

Over the years, I’ve developed a few guiding principles that I stick to when managing these challenging tumors:

- Patient Communication is Key: The patient must be thoroughly informed about all potential risks, including infectious, hemorrhagic, and neurological complications. Informed consent is paramount.

- Avoid Excessive Head Rotation: As mentioned, too much rotation can disturb the surgeon’s mental representation of the tumor and can ‘hide’ crucial medial neurovascular elements.

- Postero-lateral Orbitotomy Benefits: This enhances tumor exposure and can often avoid the need for more extensive osteotomies (bone removal).

- Early Devascularization: Extradural anterior clinoidectomy is invaluable for this, as well as for early optic nerve decompression and ICA localization.

- Maximize Exposure Safely: Extensive dissection of the sylvian fissure and arachnoid cisterns is a must for safe access and retractorless surgery.

- Systematic Identification: Always aim for clear identification of the entry and exit points in the tumor of the ACA, MCA, PComA, and AChA, along with the optic nerve and the 3rd cranial nerve.

- Bleeding Tolerance (Strategically): Tolerate some bleeding in the retrocarotid and supracarotid spaces until all vital vascular and nervous elements have been clearly identified.

- Manage Vasospasm Risk: Vasospasm is a real possibility after extensive vascular dissection. I often use local papaverine on the vessels and may employ mild postoperative hypertension to mitigate this risk.

- The Golden Rule: And this is a big one for me – It is better to hurt your ego than your patient. A small tumor residue left behind is far preferable to causing an irreversible neurological deficit. Complete resection is the goal, but not at any cost.

Final Thoughts

Parasellar meningiomas with vascular encasement undoubtedly represent one of the great surgical challenges in neurosurgery. As there are no completely reliable predictive factors to tell us beforehand if we can successfully free encased arteries, I believe a cautious, meticulous dissection should be attempted in all suitable cases. Avoiding complications demands rigorous anatomical knowledge, a well-thought-out surgical strategy, and an immense amount of patience and precision.

It’s a complex dance, but with the right approach, a deep understanding of the anatomy, and a commitment to prioritizing patient safety above all else, we can often achieve very good outcomes for patients facing these formidable tumors.

Source: Springer