Malaria Vaccine Hope: Unpacking Pf41’s Genetic Secrets in Senegal

Hey there, fellow science enthusiasts! Let’s chat about something super important: malaria. This nasty disease, caused mainly by a parasite called Plasmodium falciparum, is still a huge problem, especially in tropical places. We’re talking millions of cases and hundreds of thousands of deaths every year, hitting little kids and pregnant women the hardest. It’s a real bummer, honestly.

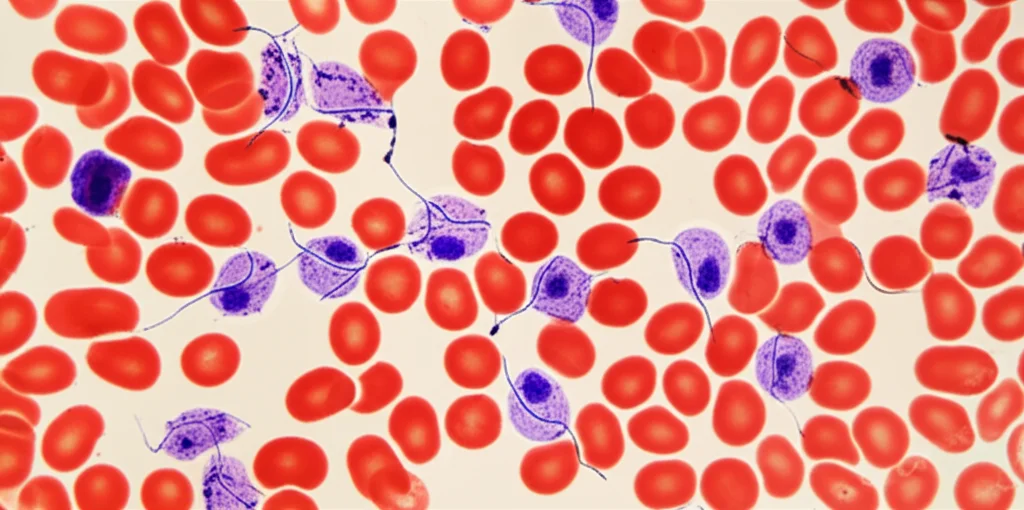

Now, we’ve got tools to fight malaria – nets, sprays, drugs – and even a couple of vaccines recently got the thumbs-up from the WHO, which is fantastic! But we still desperately need more effective vaccines, especially ones that can tackle the parasite during its blood stage, when it invades our red blood cells and makes us sick. See, when the parasite is doing its thing inside our blood cells, it’s exposed to our immune system, so targeting proteins on its surface at this stage makes a lot of sense. Our bodies *can* develop antibodies against these proteins naturally, offering some protection.

The tricky part? These parasites are sneaky! Their surface proteins can be super diverse, like they’re constantly changing their outfits. If a vaccine targets just one “outfit,” the parasite can just switch to another, and the vaccine won’t work anymore. So, finding a vaccine candidate that *doesn’t* change much across different parasite strains and places is key.

Enter Pf41: A Potential New Player

Scientists have been looking at loads of potential vaccine candidates, and one that popped up on the “top 10” list is a protein called Pf41. It’s found on the surface of the merozoite (that’s the stage that invades red blood cells) and seems to be involved in binding to those cells. Pretty important job, right? Plus, people who’ve had malaria before often have antibodies against Pf41, which is a good sign that it might trigger a protective immune response.

What’s cool about Pf41 is that it belongs to a family of proteins with these distinctive “6-Cys” domains (that means they have six conserved cysteine amino acids in a specific pattern). These 6-Cys proteins do all sorts of vital jobs throughout the parasite’s life cycle. While the function of the blood-stage ones like Pf41 isn’t totally clear yet, their structure and location make them interesting targets.

But here’s the big question: Is Pf41 diverse like some other malaria proteins (looking at you, MSP-1 and MSP-2!), or is it more conserved like others (like CSP or AMA-1)? Knowing this is crucial before we get too excited about it as a vaccine. If it’s highly variable, a vaccine based on it might only work against certain parasite strains, which isn’t ideal for a global problem like malaria.

What Did This Study Do?

So, that’s where this study comes in! These researchers wanted to get a handle on the genetic diversity and see if natural selection was shaping the Pf41 gene in P. falciparum parasites collected from people in Senegal. Senegal is a place where malaria is still a big deal, so studying parasites from there gives us real-world insights.

They gathered samples from over a hundred patients across different regions in Senegal, including Dielmo (a long-term study site) and some areas in the south where malaria is still super active. They specifically looked for P. falciparum DNA in these samples.

Once they found the positive samples, they zeroed in on the Pf41 gene. They used special techniques (PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing) to read the genetic code of Pf41 from these parasites. Out of 116 samples tested, 108 were positive for P. falciparum, and they managed to successfully sequence the Pf41 gene from 73 of them. That’s a pretty good haul!

With the sequences in hand, they dove into the data using population genetics tools. Think of it like figuring out the family tree and evolutionary pressures on this specific gene within the parasite population in Senegal. They looked at things like:

- How many differences there were between the sequences (genetic diversity).

- How many unique versions (haplotypes) of the gene were floating around.

- Whether certain parts of the gene were changing a lot (positive selection) or staying the same (negative selection).

- If different changes in the gene were linked together (linkage disequilibrium).

They used some fancy software (like DnaSP, Datamonkey Hyphy, and Popart) to crunch the numbers and visualize the results, including building a network showing how the different Pf41 haplotypes were related and where they were found geographically.

Okay, So What Did They Find?

This is where it gets interesting for vaccine development!

First off, they found that the overall genetic diversity of the Pf41 gene in these Senegalese isolates was *low*. Like, really low compared to some other malaria vaccine candidates or even compared to the same gene in a different malaria species (P. vivax). This is potentially *great* news for a vaccine, as low diversity means a vaccine is more likely to work against a wider range of parasites.

However, they also found high *haplotype* diversity. This might sound contradictory, but it means there were many different unique combinations of the small number of genetic changes they found. The study suggests this could be linked to linkage disequilibrium – basically, certain genetic variations tend to stick together when the parasite reproduces.

When they looked at which parts of the Pf41 gene were under pressure from natural selection, they saw a mix:

- The highly conserved 6-Cys domains seemed to be under *negative selection*. This means changes in these regions are often harmful to the parasite, so they tend to stay the same over time. This is also good for a vaccine, as these functional parts are conserved.

- But, the central domain of Pf41 showed signs of *balancing selection*. This type of selection can happen when different versions of a gene are favored at different times or in different people, often driven by the host’s immune system trying to recognize the parasite. It suggests this region might be under immune pressure, leading to some variation.

- They pinpointed specific sites (codons) within the gene that were under positive selection (changes are favored) and negative selection (changes are harmful).

One really notable finding was a specific single nucleotide change (SNP) at position 232, which results in an amino acid change from Serine to Arginine (S232R). This SNP was found to be “fixed” by positive selection in the Senegalese isolates they studied. This means this particular version became very common, likely because it offered some advantage to the parasite, perhaps helping it evade the immune system or bind to red blood cells better.

When they looked at the different versions (haplotypes) of Pf41 based on amino acid changes, they found 23 different ones! But only two were really common and found across all the study sites: H_1 (KSKKLKRYQNTQE) and H_2 (KSKKLKHYQNTQE). The rest were pretty rare. The presence of many low-frequency haplotypes, along with the detected linkage disequilibrium, could influence how a vaccine targeting Pf41 would work.

Why Does This All Matter for a Vaccine?

Okay, let’s connect the dots. The low overall genetic diversity of Pf41 is a big plus. It suggests that a vaccine based on this protein could potentially be effective against many different parasite strains. The conserved 6-Cys domains, being under negative selection, are likely crucial for the protein’s function and less likely to change dramatically, making them good targets too.

However, the signs of balancing selection and positive selection in the central domain, particularly the fixed S232R mutation, raise questions. Could these variations allow the parasite to escape the immune response generated by a vaccine based on the 3D7 reference strain (which doesn’t have this mutation)? The linkage disequilibrium also means that variations might travel together, potentially complicating things for vaccine efficacy.

The fact that there are many different haplotypes, even if most are rare, is also something to consider. A vaccine might need to include the most common haplotypes or be designed in a way that covers the existing diversity.

This study is the first to really dig into the genetic diversity of Pf41 in clinical samples from Senegal, and it gives us valuable clues. It supports the idea that Pf41 is a promising candidate because of its overall low diversity and conserved functional parts. But it also highlights specific regions and mutations (like S232R) that need more attention.

What’s Next?

The researchers themselves point out that this is just a starting point. They used a limited number of samples compared to the vast number of malaria cases out there. To really understand the potential of Pf41, we need:

- Studies with many more samples from different places around the world and different time periods to see how diversity and selection patterns vary.

- Functional studies to figure out exactly what those mutations, especially in the central domain, actually *do*. Do they affect how Pf41 binds to red blood cells? Do they help the parasite hide from the immune system?

Understanding these things will help scientists decide if and how to include Pf41 in a multi-component malaria vaccine – one that targets several different parasite proteins to give the immune system multiple ways to fight back.

So, while Pf41 looks like a good prospect on paper thanks to its low diversity and conserved bits, the signs of selection pressure in certain areas mean we need to be smart about how we use it. It’s another piece of the puzzle in the complex fight against malaria, and every bit of knowledge helps us get closer to a world free from this disease. Pretty cool stuff, right?

Source: Springer