Sweet Relief? New Drug LY3522348 Targets Fructose for Liver Health

Hey there! Let’s dive into something pretty interesting happening in the world of medicine. We’re talking about a brand new player on the scene, a potential game-changer called LY3522348. Now, that’s a bit of a mouthful, I know, but stick with me, because what it does is pretty cool, especially if you’re thinking about liver health.

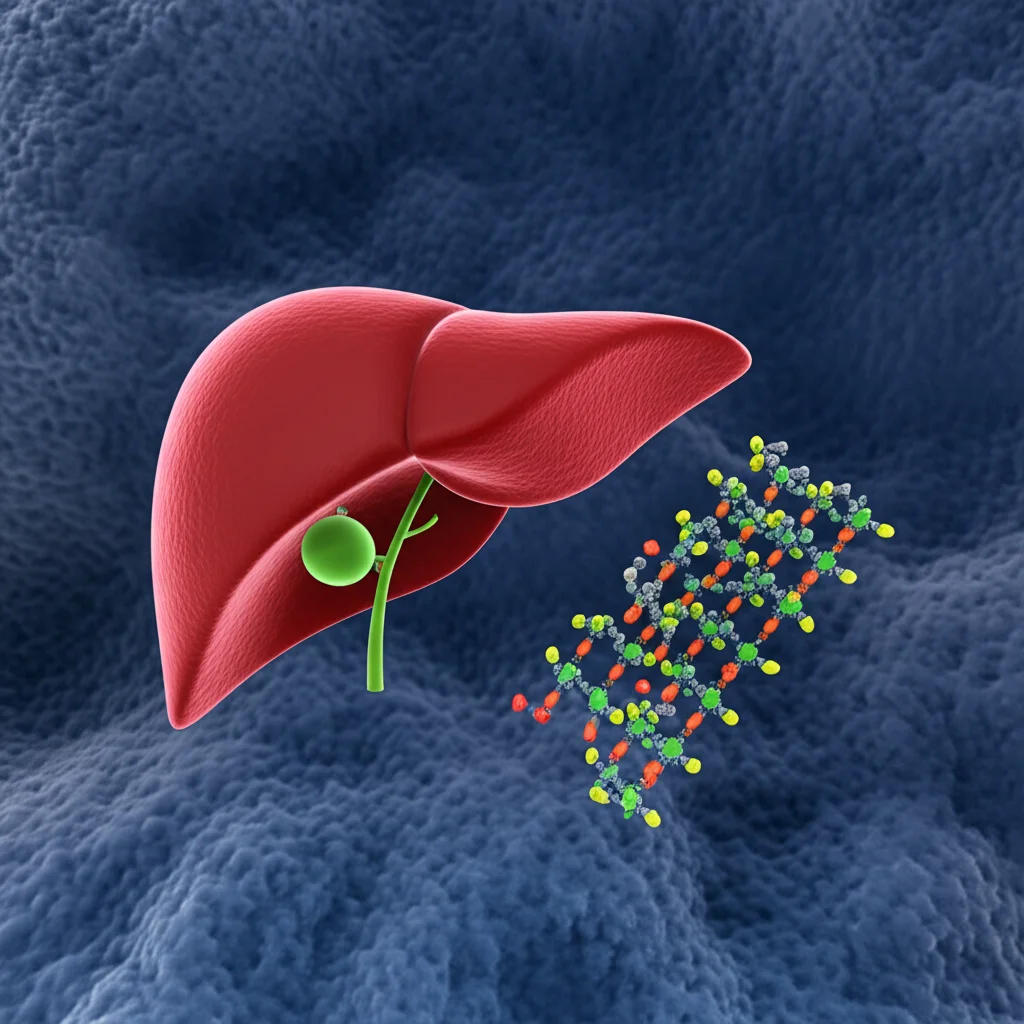

You see, our livers are amazing organs, but they can get a bit overloaded, especially with the way many of us eat these days. One of the things that can cause trouble is fructose, that sweet stuff found in everything from fruit to, well, *lots* of processed foods. When we consume too much fructose, our liver metabolizes it, and this process can sometimes lead to something called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), or what you might have heard called fatty liver disease. And if that gets worse, it can turn into metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), which is a more serious form.

Why Fructose is a Culprit and How KHK Fits In

So, why is fructose such a big deal for the liver? Well, unlike glucose, which most of our body cells can use for energy, fructose is primarily processed in the liver. There’s a key enzyme in the liver called ketohexokinase (KHK) that kicks off the whole process of breaking down fructose. Think of KHK as the gatekeeper for fructose metabolism in the liver. When there’s too much fructose coming in, KHK works overtime, and this can lead to a cascade of events:

- Increased fat production in the liver (de novo lipogenesis).

- Reduced ability of the liver to burn fat.

- Inflammation in the liver.

All of these things contribute to MASLD and its progression to MASH. It’s like the liver gets overwhelmed and starts storing fat instead of processing it efficiently.

Now, here’s where LY3522348 comes in. It’s designed to be a highly selective inhibitor of KHK. Basically, it’s meant to block that gatekeeper enzyme. The idea is that by slowing down the liver’s processing of fructose, we might be able to reduce fat buildup and inflammation, potentially helping with MASLD and MASH. It’s a bit like putting a speed bump on the fructose highway into the liver.

Interestingly, studies have shown that people who naturally have a deficiency in KHK don’t seem to suffer negative health consequences, even though they have higher levels of fructose circulating in their blood (because their bodies aren’t processing it as quickly). This suggests that inhibiting KHK might be a safe way to tackle the problem.

The First Look: A Study in Healthy Adults

Before we can even think about using a drug like LY3522348 in people with liver disease, we need to make sure it’s safe and understand how it behaves in the human body. That’s exactly what this study was all about – a first-in-human Phase 1 trial in healthy adults.

The study had a couple of parts:

- Single-Ascending Dose (SAD): Participants received just one dose of LY3522348, with different groups getting increasing amounts (from 5 mg up to 380 mg).

- Multiple-Ascending Dose (MAD): Participants received the drug once daily for 14 days, again with different groups getting increasing doses (50 mg, 120 mg, and 290 mg).

They also did a little test to see if LY3522348 messed with how the body processes another common drug (midazolam), which tells us something about potential drug interactions.

The main goals were to check:

- Safety and Tolerability: Did people have side effects? Were they serious?

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): How did the body absorb, distribute, metabolize, and excrete the drug? How long did it stay in the system?

- Pharmacodynamics (PD): Did the drug actually do what it was supposed to do? In this case, did it inhibit fructose metabolism?

They had a total of 65 healthy folks participate, carefully selected based on health criteria. They monitored them closely with physical exams, lab tests, vital signs, and ECGs.

What We Learned: Safety First!

Okay, so what were the results? This is the exciting part!

First off, the big news is that LY3522348 was well tolerated by the participants. Most of the side effects reported were mild. Things like nausea or a headache were mentioned, but nothing serious popped up, and thankfully, no one had to drop out of the study because of side effects, and there were no deaths reported. This is super important for a new drug – safety is always the top priority in these early studies.

They did notice a slight dose-related decrease in diastolic blood pressure in the multiple-dose part of the study, but overall, vital signs and ECGs looked good.

Understanding How the Body Handles It (PK)

Next up, the pharmacokinetics (PK). This tells us how the drug moves through the body. The analysis showed that as the dose increased, the amount of drug in the bloodstream also increased in a pretty predictable, dose-proportional way. That’s good because it means we can likely control the drug’s exposure by adjusting the dose.

The drug also hung around for a decent amount of time – the half-life ranged from about 23.7 to 33.8 hours. This suggests that taking the drug just once a day could be enough to keep levels stable in the body, which is great for patient convenience!

The study also checked how much of the drug was excreted unchanged in the urine, and it was a relatively small amount (around 3.76% to 6.32%), indicating the body is primarily processing it in other ways.

Did It Do the Job? (PD)

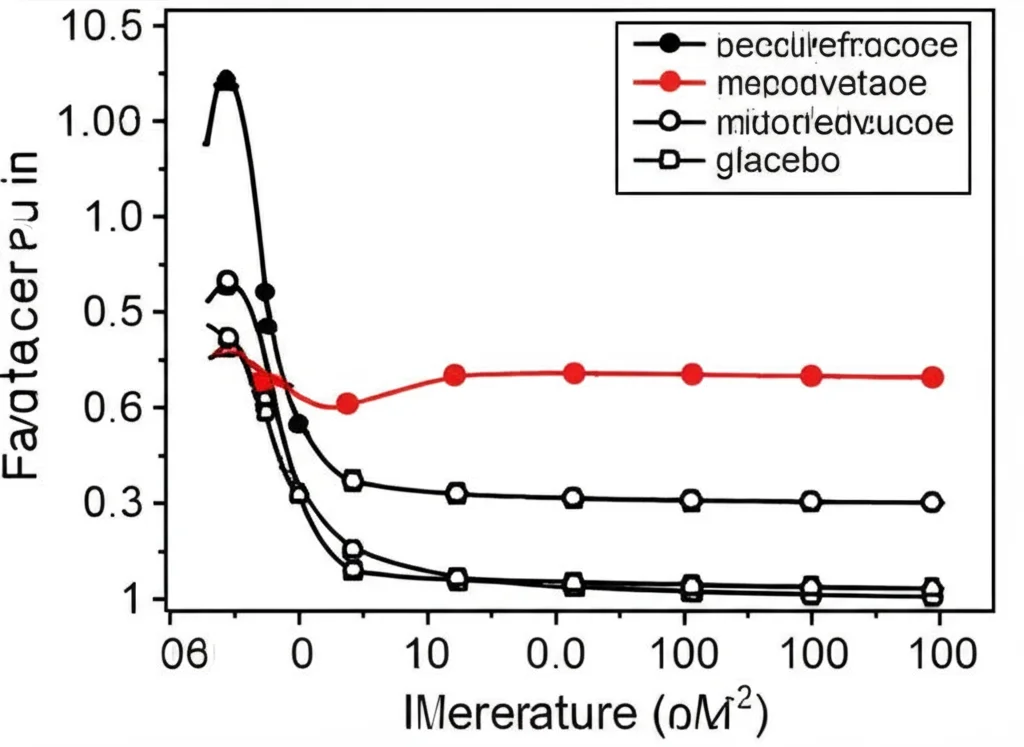

Now for the pharmacodynamics (PD) – did LY3522348 actually inhibit fructose metabolism in humans? To test this, participants were given a fructose beverage after taking the drug or a placebo. Then, researchers measured the levels of fructose in their blood over time.

And guess what? The results were clear! Participants who received LY3522348 had a dose-dependent increase in plasma fructose concentrations compared to those who got the placebo. This is exactly what you’d expect if the drug is blocking KHK – the fructose isn’t being processed as quickly by the liver, so it stays in the bloodstream longer. This confirms that LY3522348 is effectively engaging its target, KHK, and inhibiting fructose metabolism in humans. Pretty cool confirmation, right?

For example, in the single-dose study, the highest dose (380 mg) led to an over 8-fold increase in the area under the fructose concentration curve compared to placebo. In the multiple-dose study, the effect was also clear, with the highest dose (290 mg) causing a significant increase in fructose levels after the challenge on both day 1 and day 14.

Interestingly, in this short study, they didn’t see significant changes in cholesterol or triglyceride levels. This isn’t surprising for a short-term study in healthy volunteers, as the metabolic benefits related to fat reduction are expected to take longer and would be more relevant in people with MASLD/MASH.

The drug interaction test with midazolam also suggested that LY3522348 isn’t likely to cause major issues by interfering with a common drug metabolism pathway (CYP3A).

What This Means and Looking Ahead

So, what’s the takeaway from this first-in-human study?

Essentially, LY3522348 looks promising so far. It was safe and well-tolerated in healthy adults, it has pharmacokinetic properties that support once-daily dosing, and most importantly, it *works* as intended by effectively inhibiting fructose metabolism in humans.

This study lays the groundwork for future research. The next step would typically be to test LY3522348 in people who actually have MASLD or MASH to see if inhibiting KHK translates into real clinical benefits, like reducing liver fat, inflammation, and fibrosis.

It’s worth noting that the landscape for treating MASLD/MASH is evolving, with other types of drugs, like GLP-1 receptor agonists, showing good results. Future studies will need to compare the efficacy of KHK inhibitors like LY3522348 to these emerging treatments.

This study was limited by its small size and focus on healthy participants, but that’s standard for a Phase 1 trial. It achieved its goals of assessing safety, PK, and confirming target engagement.

In conclusion, this study gives us a solid foundation. We now know that LY3522348 is safe enough to move forward, behaves predictably in the body, and successfully puts the brakes on fructose metabolism. It’s an exciting step in exploring KHK inhibition as a potential strategy to help tackle liver diseases linked to fructose overload.

Source: Springer