Cracking the Code: How a Tiny Molecule Fights Lung Cancer’s Radiation Resistance

Hey there! Let’s chat about something super important: lung cancer. It’s a massive health challenge worldwide, and while we’ve got tools like radiotherapy in our arsenal, especially for those advanced stages where surgery isn’t an option, we often hit a wall. That wall? Tumors becoming resistant to the treatment. It’s frustrating, right? We zap ‘em, and they just… shrug it off. So, we’ve been digging into *why* this happens, looking for new ways to make radiotherapy work better.

The Big Problem: Radiotherapy Resistance

Lung cancer is a tough one. In 2018, it was responsible for a huge chunk of cancer deaths globally. And even now, thousands of new cases pop up every year in places like the US. Non-small cell lung cancer, or NSCLC, is the most common type. For many patients, especially if it’s caught late, radiotherapy is a crucial part of their treatment plan. It helps manage symptoms and can really make a difference. But, as I mentioned, tumors can get resistant, and that makes treatment less effective.

We know that this resistance isn’t just bad luck; it’s driven by complex stuff happening inside the cancer cells. Things like genetic changes, how genes are regulated after they’re transcribed (that’s called post-transcriptional regulation), and how the cells repair themselves after the radiation hits them.

Enter the Players: miR-7-5p and PKP2

Our investigation led us to look at tiny molecules called microRNAs, or miRNAs. Think of them as little conductors in the cell, telling other genes when to quiet down. They’re non-coding RNAs, super small, and they work by latching onto messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and stopping them from making proteins. Scientists are finding that miRNAs are pretty important in how tumors respond to radiotherapy. Some can make cells more sensitive, others less so.

One miRNA that’s caught a lot of attention is miR-7-5p. It pops up in studies about various cancers and seems to play a role in tumor growth and progression. It’s even been linked to how cancers respond to chemotherapy. For example, some studies show miR-7-5p helping to overcome resistance to drugs like cisplatin in lung cancer.

Then there’s PKP2 (plakophilin-2). It’s a protein that’s part of a family involved in cell structure and signaling. PKP2 has been implicated in several cancers, like ovarian and colon cancer. And, importantly for us, recent work, including some of our own previous studies, showed that PKP2 is often found at high levels in lung cancer and seems to help the cancer grow. Even more interesting, we found that PKP2 might be giving cancer cells a hand in shrugging off radiation by boosting their ability to repair damaged DNA, specifically through a process called non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).

Our Quest: Connecting the Dots

So, we had miR-7-5p, known to influence cancer and potentially drug resistance, and PKP2, which we suspected was a key player in radiotherapy resistance by fixing DNA damage. We wondered: Could miR-7-5p be controlling PKP2? And if so, could this connection explain some of that frustrating radiotherapy resistance in NSCLC?

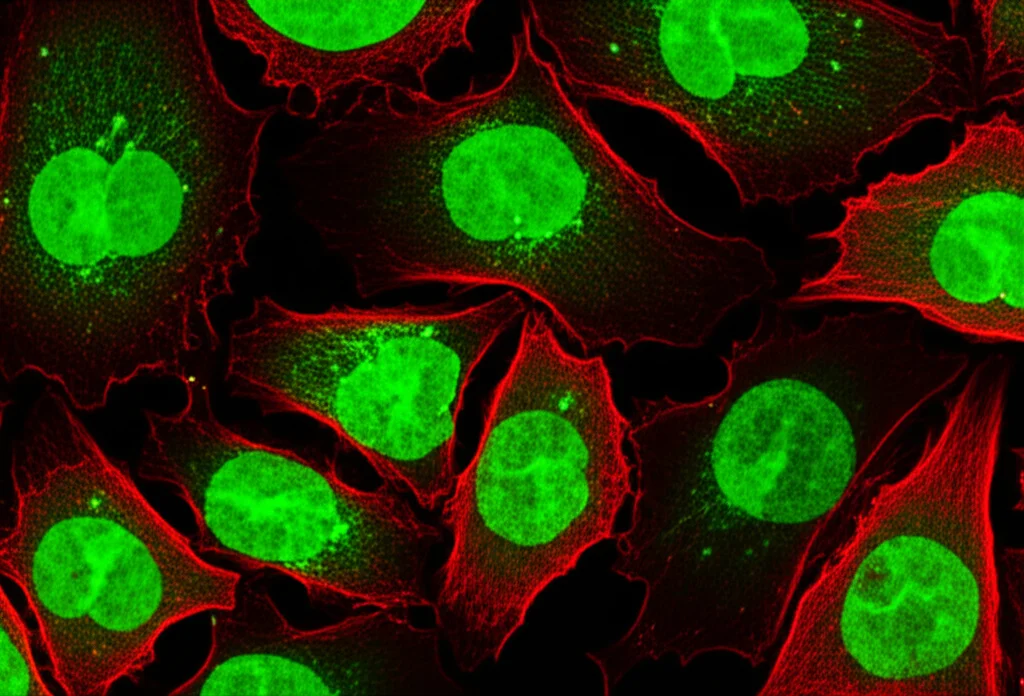

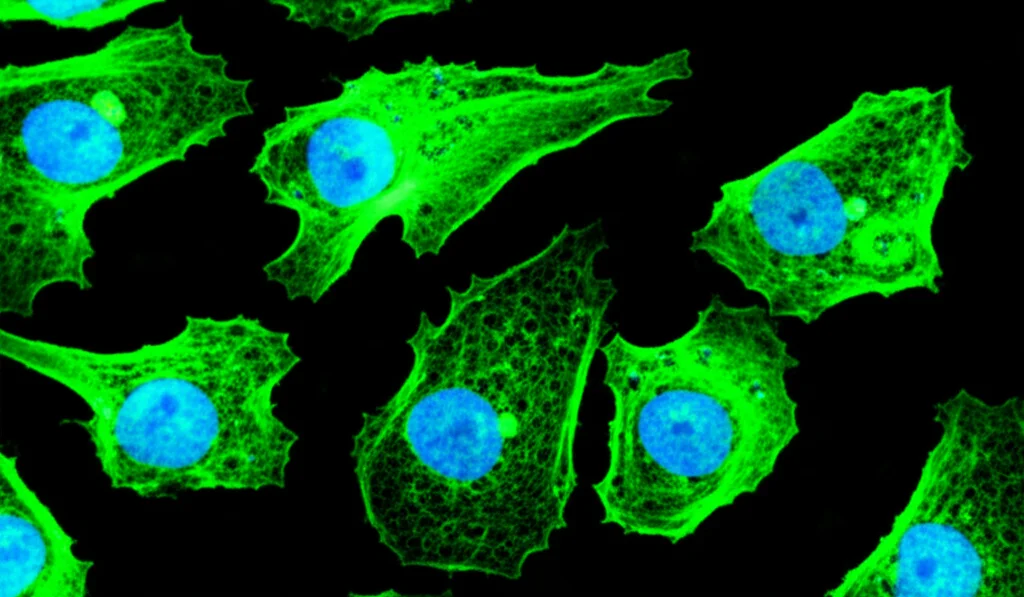

We decided to get our hands dirty in the lab using A549 NSCLC cells, a standard cell line for this kind of research. We did all sorts of tests – looking at how many cells survived radiation (clonogenic assays), how healthy they were (CCK-8 assays), checking out proteins (Western blotting), and even using fancy reporter genes to see if miR-7-5p directly targets PKP2.

What We Found: miR-7-5p Puts the Brakes on PKP2 and Resistance

The results were pretty compelling! When we boosted the levels of miR-7-5p in the A549 cells, they became much more sensitive to radiation. They didn’t survive as well, and their overall viability dropped significantly after being zapped compared to the control cells. On the flip side, when we lowered miR-7-5p, the cells became *more* resistant.

Radiation works by damaging DNA, particularly causing double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are pretty catastrophic for a cell if not fixed. A key marker for these breaks is a modified protein called γ-H2AX. We looked at γ-H2AX levels and found that when we increased miR-7-5p, there were significantly more γ-H2AX foci (those are little spots showing damage) after radiation. This suggests that miR-7-5p helps the radiation cause more lasting damage, or perhaps hinders the initial repair response.

Speaking of repair, we focused on NHEJ, a major pathway cells use to fix those nasty DSBs. Using a specific reporter system, we saw that boosting miR-7-5p significantly *decreased* the activity of the NHEJ repair pathway. Less repair means more damage sticks around, which is exactly what you want when you’re trying to kill cancer cells with radiation. Conversely, inhibiting miR-7-5p cranked up the NHEJ repair activity.

PKP2: The Direct Target

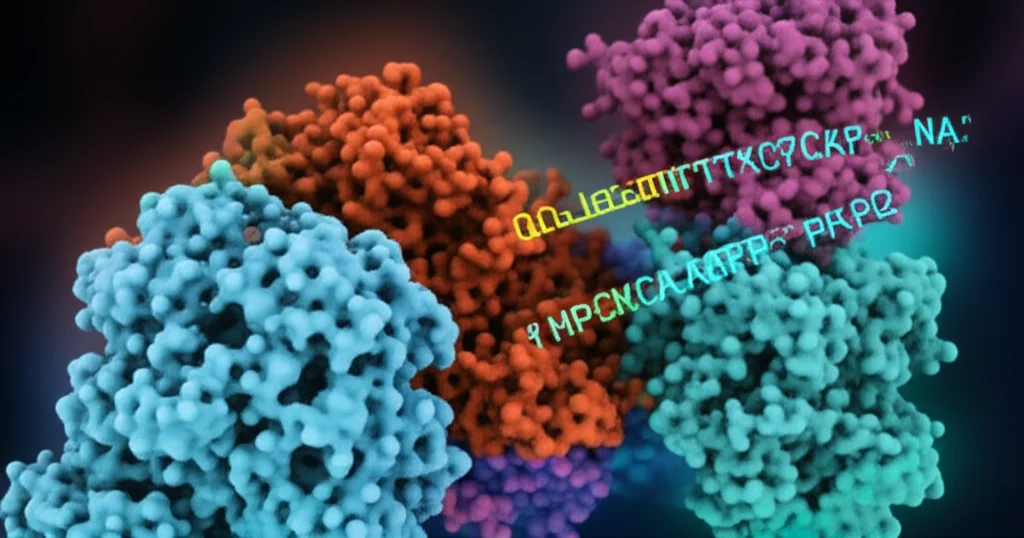

Okay, so miR-7-5p makes cells sensitive by increasing damage and reducing repair. But how? This is where PKP2 comes back in. We used bioinformatics tools (basically, powerful computer programs scanning databases) to predict which genes miR-7-5p might be targeting. And guess what? PKP2 popped up consistently across multiple databases as a prime candidate.

miRNAs bind to specific sequences, usually in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of an mRNA. Our analysis showed a strong predicted binding site for miR-7-5p on the PKP2 mRNA. To prove this wasn’t just a computer’s best guess, we did a dual-luciferase reporter assay. This is a neat trick where we link the PKP2 3’UTR to a gene that makes light (luciferase). If miR-7-5p binds to that UTR, it should reduce the light signal. And that’s exactly what happened! When we added miR-7-5p, the light from the normal PKP2 UTR dropped significantly, but not from a modified UTR where we’d messed up the binding site. This confirmed that miR-7-5p directly binds to the PKP2 mRNA.

We then checked what this binding does to PKP2 levels in the cells. Using Western blotting, we saw that increasing miR-7-5p significantly reduced PKP2 protein levels. Lowering miR-7-5p had the opposite effect, increasing PKP2. We also looked at PKP2 mRNA levels using qRT-PCR and found that miR-7-5p reduced those too. This suggests miR-7-5p isn’t just stopping PKP2 from being made, but might also be causing the PKP2 mRNA to be degraded. Either way, more miR-7-5p means less PKP2.

Putting It All Together: The miR-7-5p/PKP2 Axis

Now for the crucial test: Does miR-7-5p make cells sensitive *because* it’s targeting PKP2? To figure this out, we boosted miR-7-5p in the cells (which normally makes them sensitive) and then *also* artificially increased PKP2 levels. If PKP2 is the key, adding it back should reverse the sensitivity caused by miR-7-5p.

And that’s precisely what happened! When we overexpressed PKP2 in the miR-7-5p-boosted cells, they became more resistant to radiation again. Their ability to form colonies after radiation improved, and the increased DNA damage (γ-H2AX foci) we saw with high miR-7-5p was reduced when PKP2 was also high. Crucially, the reduced NHEJ activity caused by miR-7-5p was also partly reversed by overexpressing PKP2.

This strongly suggests that the miR-7-5p/PKP2 pathway is a major regulator of how sensitive NSCLC cells are to radiotherapy. When miR-7-5p is low, PKP2 levels are likely high, leading to more efficient DNA repair (NHEJ) and increased resistance. When miR-7-5p is high, it suppresses PKP2, hindering repair and making the cells more vulnerable to radiation.

What This Means for the Future

So, why is all this important? Well, understanding *how* cancer cells become resistant is the first step to overcoming it. Our findings highlight the miR-7-5p/PKP2 axis as a key player in NSCLC radiotherapy resistance. This is pretty exciting because it gives us a potential target for new therapies.

Imagine if we could develop ways to mimic the effects of high miR-7-5p, or directly inhibit PKP2, specifically in the tumor cells. This could potentially make radiotherapy much more effective for patients whose tumors are currently resistant, leading to better outcomes and hopefully saving more lives.

Now, science is complex, and it’s worth noting that sometimes these molecules can have different roles depending on the specific cancer type or context. We saw a hint of this when looking at other studies – one suggested miR-7-5p might even contribute to resistance in a different setting by affecting iron levels. This just underscores how intricate these biological networks are and why context-specific research like ours is so vital.

But in the context of NSCLC and the mechanisms we studied (DNA damage and NHEJ repair), our results are clear: PKP2 is a novel target of miR-7-5p, and this interaction significantly impacts radiosensitivity. Targeting this pathway holds real promise for enhancing radiotherapy and improving the prognosis for many lung cancer patients.

There’s still work to be done, of course. We need to explore this further, maybe in more complex models or even eventually in clinical trials. But finding this key connection between miR-7-5p and PKP2 gives us a solid lead in the fight against radiotherapy resistance. It’s one more piece of the puzzle, bringing us closer to making cancer treatments more effective.

Source: Springer