Unlocking Ovarian Reserve Secrets: How a Tiny RNA Holds the Key

Hey there! Let’s dive into something super important for women’s health and fertility: diminished ovarian reserve, or DOR. Think of it as the ovaries running out of steam a bit sooner than they should, leading to fewer eggs and often making getting pregnant a real challenge. It seriously impacts women’s lives, and while hormone therapy can help with symptoms, it doesn’t fix the core issue of declining ovarian function. So, understanding *why* this happens is crucial for finding better ways to help.

Our ovaries are amazing, and a big part of their magic comes from tiny cells called granulosa cells (GCs). These little powerhouses surround the developing eggs (follicles) and are key players in making hormones, especially estrogen. They also chat constantly with the eggs, helping them grow and mature. If these GCs aren’t happy – if they’re dying off too much (apoptosis) or not growing enough (proliferation), or not making enough hormones – the follicles suffer, and that leads straight to DOR.

This is where the fascinating world of genetics comes in, specifically something called long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). Don’t let the name scare you! These are molecules made from DNA, just like the instructions for making proteins (mRNAs), but they don’t actually code for proteins themselves. Instead, they act like little regulators, influencing how other genes are turned on or off, or how their messages are handled. They’re like the conductors of the cellular orchestra, making sure everything plays in tune.

Our Previous Clue: The Case of NEAT1

In our previous work, we peeked inside the GCs of women with DOR and found something interesting: a specific lncRNA called NEAT1 was significantly *downregulated*. Basically, there was less of it in women with DOR compared to those with normal ovarian reserve. This got us thinking: could NEAT1 be involved in DOR? But the exact *how* was still a mystery.

So, in this study, we set out to uncover NEAT1’s role. We wanted to see if its low levels in DOR were really linked to how well the ovaries were functioning and even to the success rates of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) like IVF. More importantly, we wanted to figure out the molecular dance NEAT1 was doing inside the GCs to affect their health and function.

NEAT1’s Link to Ovarian Health

First off, we confirmed that in the GCs from women with DOR, NEAT1 expression was indeed much lower. And guess what? This low NEAT1 level wasn’t just a random finding. We found a strong connection between how much NEAT1 was present and key markers of ovarian reserve, like AMH and AFC (which tell us about the egg supply), and FSH (a hormone that gets high when ovarian function declines). Higher NEAT1 meant better ovarian markers.

Even more exciting, NEAT1 levels correlated positively with ART outcomes – things like the number of eggs retrieved and the quality of embryos. This really suggested that NEAT1 isn’t just *present* in GCs; it seems to be *important* for their function and, by extension, for successful reproduction.

What NEAT1 Does Inside the Cell

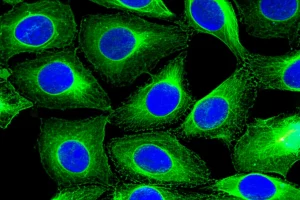

To understand NEAT1’s job, we worked with a human ovarian GC cell line called KGN. We first checked where NEAT1 hangs out inside these cells. Using a technique called FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization), we saw that NEAT1 is mainly located in the cytoplasm. This is a big clue! LncRNAs in the cytoplasm often act as “molecular sponges” for tiny regulatory molecules called microRNAs (miRNAs).

Think of miRNAs as little snippets of RNA that can bind to and silence other RNA molecules (like the instructions for making proteins). A lncRNA acting as a sponge can soak up specific miRNAs, preventing them from doing their silencing job on other targets.

We then manipulated NEAT1 levels in our KGN cells. When we increased NEAT1, the cells grew and multiplied better (proliferation) and were less likely to die off (apoptosis). When we decreased NEAT1, the opposite happened – less growth, more death. We also looked at the cell cycle, the process cells go through to divide. Increasing NEAT1 pushed cells into the “S phase,” which is when they copy their DNA before dividing, indicating more proliferation. Lowering NEAT1 blocked cells in an earlier phase, stopping them from dividing. This told us NEAT1 is a friend to GC health and growth.

Finding NEAT1’s Dance Partner: miR-204-5p

Since NEAT1 was in the cytoplasm and seemed to act like a sponge, we used fancy computer tools (bioinformatics) to predict which miRNAs it might be sponging. Several candidates popped up, but one, miR-204-5p, caught our eye because it was predicted by multiple databases *and* we found it was significantly *upregulated* in the GCs of women with DOR (remember, NEAT1 was downregulated – they seem to be opposites!).

We then did experiments (dual-luciferase reporter assays) that are like molecular lie detectors to see if NEAT1 and miR-204-5p really bind directly. The results were clear: miR-204-5p *does* bind to NEAT1. Furthermore, increasing NEAT1 in cells decreased miR-204-5p levels, and decreasing NEAT1 increased miR-204-5p. This confirmed that NEAT1 acts like a sponge, soaking up miR-204-5p and reducing its availability.

What Happens When miR-204-5p is High?

Next, we wanted to see what miR-204-5p does on its own to KGN cells. When we increased miR-204-5p, cell growth and viability went down, and apoptosis went up. When we decreased miR-204-5p, the cells thrived – more proliferation, less apoptosis. This is the exact opposite effect of NEAT1, which makes perfect sense if NEAT1 is sponging miR-204-5p to keep its levels low.

To really nail this down, we did a “rescue” experiment. We increased NEAT1 (which normally makes cells happy) but *also* increased miR-204-5p at the same time. What happened? The positive effects of NEAT1 on cell proliferation and apoptosis were *reversed* by the extra miR-204-5p. This strongly suggests that NEAT1 exerts its protective effects on GCs largely by sponging miR-204-5p.

Discovering miR-204-5p’s Target: ESR1

Okay, so NEAT1 sponges miR-204-5p, and miR-204-5p is bad for GC health. But *how* does miR-204-5p cause trouble? miRNAs work by targeting other genes, specifically their mRNA instructions. We went back to our bioinformatics tools to predict which genes miR-204-5p might be targeting. One gene that stood out was ESR1, which codes for Estrogen Receptor alpha. ESR1 is super important in the ovaries, mediating estrogen signaling and affecting follicle development and hormone synthesis.

We found that ESR1 expression was significantly *downregulated* in the GCs of women with DOR (just like NEAT1, and opposite to miR-204-5p). Our dual-luciferase assays confirmed that miR-204-5p directly binds to the ESR1 mRNA. And when we increased miR-204-5p in KGN cells, ESR1 levels (both mRNA and protein) went down. Decreasing miR-204-5p increased ESR1. This shows that miR-204-5p negatively regulates ESR1 expression.

Another rescue experiment confirmed the miR-204-5p/ESR1 link. We decreased miR-204-5p (which normally makes cells happy by increasing ESR1), but *also* silenced ESR1. Silencing ESR1 reversed the positive effects of low miR-204-5p on cell proliferation and apoptosis. This means miR-204-5p is likely causing its negative effects on GCs by targeting and reducing ESR1.

The Full Pathway: ESR1, Hormones, and Cell Signals

ESR1 isn’t just sitting there; it’s involved in important processes. It helps regulate the synthesis of steroid hormones like estradiol (E2) by influencing key enzymes like StAR and CYP19A1. We found that decreasing miR-204-5p (which increases ESR1) boosted the expression of these enzymes and increased E2 production. Silencing ESR1 reversed this, confirming ESR1’s role in hormone synthesis.

ESR1 also activates a crucial cellular communication system called the MAPK signaling pathway. This pathway is like a relay race inside the cell, passing signals that control things like cell growth, division, and survival. Key players in this pathway are proteins like ERK and CREB, which get “phosphorylated” (activated) when the pathway is on.

We saw that decreasing miR-204-5p (which increases ESR1) significantly increased the activation (phosphorylation) of ERK and CREB. Silencing ESR1 blocked this activation. This clearly showed that ESR1 is an upstream activator of the MAPK pathway in these cells. Since the MAPK pathway is known to promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis, this fits perfectly with what we saw happening with cell growth and death.

Putting the Pieces Together: The NEAT1/miR-204-5p/ESR1 Axis

So, here’s the beautiful, intricate picture that emerged:

- In healthy GCs, NEAT1 is present at normal levels.

- NEAT1 acts as a sponge, soaking up miR-204-5p.

- By sponging miR-204-5p, NEAT1 reduces the amount of “free” miR-204-5p available to target other genes.

- With less miR-204-5p around, its target, ESR1, is expressed at higher levels.

- Higher ESR1 activates the MAPK signaling pathway and boosts the production of enzymes needed for estradiol synthesis.

- The activated MAPK pathway and increased steroid synthesis work together to promote GC proliferation and survival, and support hormone production.

Now, what happens in DOR? Our findings suggest:

- NEAT1 levels are low in DOR.

- With less NEAT1 sponge, miR-204-5p levels are higher.

- Higher miR-204-5p targets and reduces ESR1 expression.

- Lower ESR1 leads to less activation of the MAPK pathway and reduced steroid synthesis enzymes.

- This results in decreased GC proliferation, increased apoptosis, and lower estradiol production – the hallmarks of DOR.

We even looked at the GCs from our DOR patients again and found that, just like in our KGN cell experiments, they had lower levels of ESR1, the steroid synthesis enzymes (StAR, CYP19A1), and reduced activation of the MAPK pathway (less phosphorylated ERK and CREB). This confirms that this specific pathway, the NEAT1/miR-204-5p/ESR1/MAPK axis, seems to be malfunctioning in DOR.

Why This Matters

Discovering this specific molecular pathway gives us novel insights into *why* DOR happens at the cellular level. It highlights how tiny non-coding RNAs can have a huge impact on ovarian function. This isn’t just academic; understanding these mechanisms is the first step towards finding new ways to diagnose, prevent, or even treat DOR. Could we one day target this pathway to protect GC health and preserve ovarian reserve? It’s certainly a hopeful direction for future research.

Of course, science always has steps. While our cell line experiments were powerful, KGN cells are cancer cells and might not perfectly mimic normal GCs in every way. And these findings are primarily from *in vitro* (lab dish) experiments. The next crucial step is to test this axis in living organisms, like animal models of DOR, and with larger clinical samples to see if this holds true in a more complex biological setting. That’s definitely on our roadmap!

In a nutshell, our study paints a clearer picture of how the lncRNA NEAT1, by sponging miR-204-5p and regulating ESR1 and the MAPK pathway, plays a vital role in maintaining the health and function of granulosa cells. When this axis goes awry, it contributes to the decline seen in diminished ovarian reserve. It’s a complex puzzle, but piece by piece, we’re getting closer to understanding and hopefully finding ways to help women facing this challenge.

Source: Springer